The Big Picture | <><> |

- 2010 in Review: Pushing the Costs Down the Road

- Poll Results: Sentiment — Have the Bulls Disappeared?

- What Does Apple Want from Content Producers?

- Stocks Oil, Gold, Bonds for the Long Run?

- Time Magazine Covers & the Stock Market

- The Anti-Regulators Are the “Job Killers”

Posted: 17 Jan 2011 07:22 PM PST As 2010 dawned, the biggest debate among market participants about the year to unfold centered on Fed policy. Quantitative Easing had been announced in March of 2009 and was set to expire in March of 2010. Economists and pundits argued about just how the Fed would extricate itself from this massive bond purchase operation and most expected the fed funds rate to begin heading higher well before 2011 arrived. On the fiscal front, policy stimulus measures were supposed to wear off as the year progressed, and tax rates were set to rise as the calendar turned to 2011. Propped up as it had been by loose monetary and fiscal policies in 2009, the U.S. economy inspired little confidence that it could stand on its own two feet as 2010 got underway. And though both stock prices and longer term interest rates had risen substantially as 2009 drew to a close, the horrors of 2008 were still fresh enough in folks’ minds to make them wonder when the next shoe would drop. Investor worries ran the gamut, from withering deflation to currency debasement and inflation. Not many prognosticators had much faith in their forecasts for 2010 and neither did this one. What came to pass was a year in which most worries went unrealized. The Fed never did reverse QE 1, nor did it raise short term interest rates. The Bank of Bernanke instead saw fit to expand its balance sheet further via QE II. Our elected officials in Washington debated lower tax rates, corporate largess, and renewed government spending for most of the year before deciding in December that the word “compromise” meant “all of the above”. The year’s biggest scare came not on this side of the Atlantic but in Europe. Greece, Ireland, and the other so-called PIIGS threatened the type of defaults that might destroy the European Union itself. And yet, despite legitimate worries about the fiscal ills in peripheral Europe, the EU, ECB, and IMF stitched together just enough in the way of aid and bailouts that the currency known as the euro survived. Though each fire in Europe was doused with liquidity, the actions taken didn’t assure investors that Portugal, Spain, and others were safe. Many U.S. states, cities, and municipalities were in similar trouble for most of 2010. But, despite some disquiet in the Municipal bond market late in the year, there were none of the credit events that cause a bond insurer’s heart to skip. If 2010 had any theme at all, “kicking the can down the road” was as apt as any, especially in the industrialized West. Before I review the particulars of each prediction I made for 2010, it may be helpful to review the rationale behind them. The following is the final paragraph accompanying my guesses for 2010: “The thesis underlying most of these predictions (for 2010) is that the Fed will keep the funds rate low and do little more than talk about exits. They, as well as elected officials from both parties, will keep trying to postpone the painful costs of the 2007-2009 bailouts. Kicking the can down the road is the one truly bipartisan policy in Washington , and it was Alan Greenspan's M.O. during his entire tenure at the Fed. If I am wrong, and the FOMC does vote to begin reversing its QE purchases in March, then some of the pain I see coming sometime after this spring will instead arrive with this year's thaw. Maybe I'm wrong about Mr. Bernanke, and maybe he'll decide to do the right thing by grounding his fleet of money-dropping choppers. But to quote Jim Grant, ‘Helicopter' is who he is.’” (01/06/10) Here are last year’s predictions and how they panned out (in red): 2010 Outlook: U.S. Economy: Fed will keep short rates near zero, so recovery continues early in year. Risk of GDP slipping back toward zero increases as year progresses, but any “double dip” recession may be a 2011 story — when higher tax rates take effect. Even if the U.S. economy displays surprising strength in the first half of ’10, the resulting increase in long term interest rates should forestall that growth later this year. – Fed did keep short rates near zero. Economy did continue to recover before starting to slip back during the summer, but bailouts in Europe and QE II helped arrest the slide. I didn’t see coming the December deal to extend the Bush tax cuts for two more years.. Stocks: Trade in a wide but uneasy range. Upper end for S&P should be 1200 to 1300, while lower end should be 950 to 850. Stock picking (alpha) will be more important to returns than getting the market trend right (beta). I still prefer low-debt, high dividend paying stocks (e.g. Big Pharma), as well as companies with rising cash flows that give managements financial flexibility (with some exceptions, higher quality names do not appear to trade at high premiums to lower quality companies). I also like having exposure to what Nassim Taleb calls “positive black swans. Some of the best of these “spec plays” could be in small mining stocks (still decimated after ’08 rout), or in smaller biotechs with attractive pipelines (e.g. drug candidates beyond phase 2 — preferably beyond phase 3). Corrections of 5% to 10% can hit at any time (even in January), but either higher interest rates or higher tax rates on incomes (and capital gains!) loom as potential downside catalysts after spring. My own plan is to use rallies to take profits and/or establish hedges. – Good call on the high end (S&P topped out at 1263); not so good on the low end (low was 1011). Dividend payers and biotech worked; big pharma lagged. My “positive black swan” plays had a good year. Hedge strategies worked in the first half of the year, not in the second. Bonds: Very tough environment in 2010 and bonds deserve a minimal asset allocation for now. At these levels, Treasury investors need either geopolitical turmoil or a relapse in the economy. Since either of these outcomes will only add to the massive issuance needs of the U.S. and others in the G-8, use rallies to shorten duration and look for high quality among corporates, senior bank loans, and municipal bonds issued by well funded locales. True credit analysis will continue to be of value, since nimble active management should outperform lumbering mutual funds. – This call looked pretty stupid in the run up to QE II, but the decline in Treasurys over the final two months helped avert seller’s remorse. Even so, the yield on 10 year Treasurys actually fell more than 40 basis points. Credit analysis did pay dividends, but Munis cracked at year end. Dollar: Should weaken, but it could see intermittent rallies due to sovereign debit concerns (think: Europe), or increased geopolitical conflict (think: Iran ). Better than 50/50 chance the U.S. Dollar Index sets a new, all-time low in 2010. Favorite G-8 currency is the Canadian loon and favorite emerging market currency is Brazilian real, but the REAL question is how long can the imbalances of the dollar-centric, global fiat currency regime last? – Europe did indeed unravel in the spring (Greece) and fall (Ireland), but the dollar was little changed. Canadian dollar and Brazilian real both rose against the greenback. No regime change yet on the reserve currency front. Commodities & Precious metals: I am still long term friendly towards commodities as a store of value, but components of the CRB index should be volatile in ’10. Energy and base metals might outperform early in year, but agricultural commodities should outperform as the year progresses. Gold will be volatile, but I think the barbarous relic will set another all time high this year. Responsible central banking (i.e. rising real interest rates) and fiscal discipline by sovereign governments represent the biggest long term threats to commodities, while “anti-speculation” legislation is a nearer term risk. The potential headwinds created by either monetary or fiscal discipline, however, are much less likely to materialize than the potential tailwind of currency volatility. – Gold did set a new high and agricultural commodities did have a very good year. The CRB index rose 17.5% U.S. Housing Market: Subsidies, a Fed on hold for now, and various private capital solutions for upside-down borrowers will help U.S. housing during the first half of the year. Housing will flatten out or even suffer a relapse later this year as these tailwinds subside and long term interest rates start to rise. – Housing relapse was one of 2010′s sadder stories The Fed: Stays “All In” by keeping short term rates on hold for most of 2010. Threats by the Fed to tighten monetary policy will be idle ones unless economic growth and job growth really surprise to the upside. Should the economy slip back, expect renewed Quantitative Easing. Mr. Bernanke seems willing to risk a funding crisis down the road in order to prevent a repeat of what he has said were policy errors by the Fed in the 1930′s (i.e. they tightened too soon) – Fed stayed on hold all year and we did get QE II instead of exit strategies. Volatility: More subdued in 2010 than in past two years and should range between roughly 15/20 and 35/40 for the VIX. Geopolitical turmoil, or a disorderly fall in the U.S. dollar, are the biggest risks to the upper end of this range. – Lucky guesses on both ends of the range Credit Spreads: Credit spreads still offer value, but not nearly as much as at this time last year. Solid credit analysis will expose relative value opportunities, but at least some profits should be taken if spreads continue to compress. Volatility caused by higher long term interest rates or disorderly currency conditions could present better investment opportunities. – Spreads did continue to compress, but taking profits was the wrong strategy unless one reinvested during the European tumult. Inflation: CPI is not a worry during the early months of 2010, but it could become one later this year or in 2011 if the near zero fed funds rate overstays its welcome. Cost-push inflation (i.e. rising food and energy prices) is much more likely than demand-pull (i.e. rising wages) inflation. – Measured inflation (CPI) still largely a no-show, but cost-push inflation is gathering strength. Given that 2010 was a good year for most investors, what lessons can be learned from the year just passed? Some will say we learned that deficit spending and money-printing “work”. After all, the economy grew, stocks rose at a double digit pace, and long term interest rates fell while the dollar and inflation were quiescent. 2010 was a policy maker’s dream year, and no doubt our politicians and central bankers are pretty happy with themselves. They probably think that the aforementioned results are ends that justify the profligate means by which they were achieved. Let us hope they don’t. Let’s hope they don’t think fiscal stimulus and money-printing can cure all economic ills. Like dogs that chase cars, overly indebted nations that pursue policies of the type we saw in 2010 don’t have long lifespans. The costs can be pushed down the road, but for only so long. Short-sighted solutions have a nasty way of making long term problems worse. What happened to Greece and Ireland in 2010 should also be a lesson for policy makers. Because those nations lack a printing press, however, they are not the best analogy for what faces the U.S. going forward. Argentina has pursued reckless fiscal policies many times during the past four decades, and its central bank has tried printing money to help. Markets eventually took away the printing press by crushing the Argentine peso each time. It would be a mistake for our elected officials and unelected central bankers to think they can indefinitely keep buying time with the policies of 2009 and 2010. Worse still, their policy interventions may mask important price signals that properly functioning markets need in order to best allocate capital. It won’t be popular, but we should act now before the markets impose an even tougher solution in the future. Our leaders need to find the courage and political will to act. As we celebrate Martin Luther King day here in the U.S., let’s remember the courage Dr. King so often displayed. It may be a misplaced hope, but wouldn’t it be nice if our newly elected Congress honored Dr. King’s legacy by having the courage to face our long term fiscal problems in 2011? Certainly the last Congress displayed all too little of it in 2010. – Jack McHugh |

Posted: 17 Jan 2011 01:30 PM PST Sentiment indicators from the AAII (individual investors) and Investors Intelligence (newsletter writers) indicate that stock market sentiment is at historically high levels, and has been for a while. However, whenever I discuss stock markets with people – ranging from private investors to institutions to journalists – most of them seem to be more concerned about a looming correction in the near term than being bullish. Maybe it is just a question of communicating with different people from those participating in the surveys, but anecdotally I do not observe particularly bullish sentiment. In order to cast light on this issue, I proceeded to run my own survey to try to get a feel for how the readers of Investment Postcards and The Big Picture (Barry Ritholtz's blog) see matters. 4,004 people participated in the poll, resulting in the numbers in the table below. The comparative numbers show the following:

Source: AAII; Investors Intelligence; Investment Postcards. The results of the Investment Postcards Survey support my anecdotal observation that most people I talk to seem to be fearing a correction/pullback rather than be bullish. I have absolutely no idea why the results of my survey are so different from the others as all the surveys polled people with some interest in the stock markets and mostly from the U.S. The questions were also the same and the six-month investment horizon the same as that of the AAII. (I do not know the time period used by Investors Intelligence.) The number of participants in the AAII and Investors Intelligence Surveys were not disclosed, but I assume they are representative samples. Although 4,004 participants are not a particularly large number, I am of the opinion that it is large enough to show a pattern. The Investment Postcards Survey closed four days (including two trading days) after the others, but this should have increased the bulls/reduced the bears as market sentiment was quite upbeat over those days. What now? I am tempted to run my survey on a continuous basis for the simple reason that the results seem to support my intuitive feel to a much greater extent than that of the AAII and Investors Intelligence Surveys. But this is where I need your help on the interpretation of the results. Am I missing something somewhere? Where is the flaw in the logic? Is sentiment in reality not as overbullish as the other surveys show? Please post your remarks in the comments section of the post so that we can get the debate going. |

Posted: 17 Jan 2011 09:00 AM PST Today’s reminder of Steve Jobs’s mortality has overshadowed the rush of various news reports related to publishers using the iPad as a platform for growth. Apple chose a day that markets are closed and news outlets are running on reduced staffs or not publishing to drop this depth charge. The timing would suggest that tomorrow’s earnings report from Apple will be the usual blow-out-the-expectations success with the ever-controlling Apple hoping to jump-start the news cycle toward the company’s success rather than its vulnerability. Truth be told, Jobs’s health is now more likely an issue for Jobs himself but not his company. During the last medical leave, Tim Cook and team showed they could execute as well without Jobs as with him. All companies eventually move on from their founders. Apple is in a better position than most to do that now. Jobs’s principles are firmly embedded in the company’s culture and his team carries on his values and vision whether Jobs is bullying people in the offices or off recuperating. One important and open question remains whether Apple’s insistence on raking a substantial toll from content providers is driven by Jobs himself. The iPad has created a surge of interest from publishers to feature their content on the device. But as Apple Insider points out, the hardware company’s terms are onerous for software producers: According to a report issued Friday by deVolkskrant (via Google Translate), Apple has employed “stricter rules” for publishers, informing them that they cannot offer free iPad access to paid print subscribers. By offering free access to print subscribers, newspapers could avoid charging for access through the iPad, and can avoid paying Apple a 30 percent cut of all transactions on the App Store.As a distribution fee, 30% might not seem like much in the physical world with trucks and retailers all needing to take a cut. But in digital distribution, 30% is a huge tax on producers. Apple surely feels it deserves compensation for having built the platform and maintaining it. After all, how different is iTunes from something like a cable network? Indeed, Apple’s insistence on controlling subscriber information also mimics the cable model. But, of course, Apple isn’t paying its content producers the way that cable networks pay for the channels they carry. Magazines might actually be happy with that. One reason single-copy prices remain high is Apple’s surcharge. Magazines simply can’t undercut their newsstand prices and give Apple such a big cut without losing out in the bargain. Under the cable model, where Apple would sell bundles of content for fixed prices, the magazines could defend their print subscriber bases and expand on the iPad without doing violence to either. Apple, however, doesn’t want to be in the cable business. Nor are they content to benefit solely from the hardware sales that content availability will drive. That leaves publishers somewhat sitting on the sidelines hoping that Google’s Honeycomb will present enough of a challenge to break Apple’s logjam. Here’s David Carey from Jeremy Peters story in today’s New York Times: "I do believe that in the next year," Mr. Carey added, "with all the new developments and all the new Android devices, that the industry will have a subscription option."In other words, the biggest roadblock to realizing the ambitions for the iPad of both publishers and readers is Apple itself. With the company surging in value, the roadblock seems inexcusable and reminder than not every bit of Apple’s culture is positive or should be preserved. |

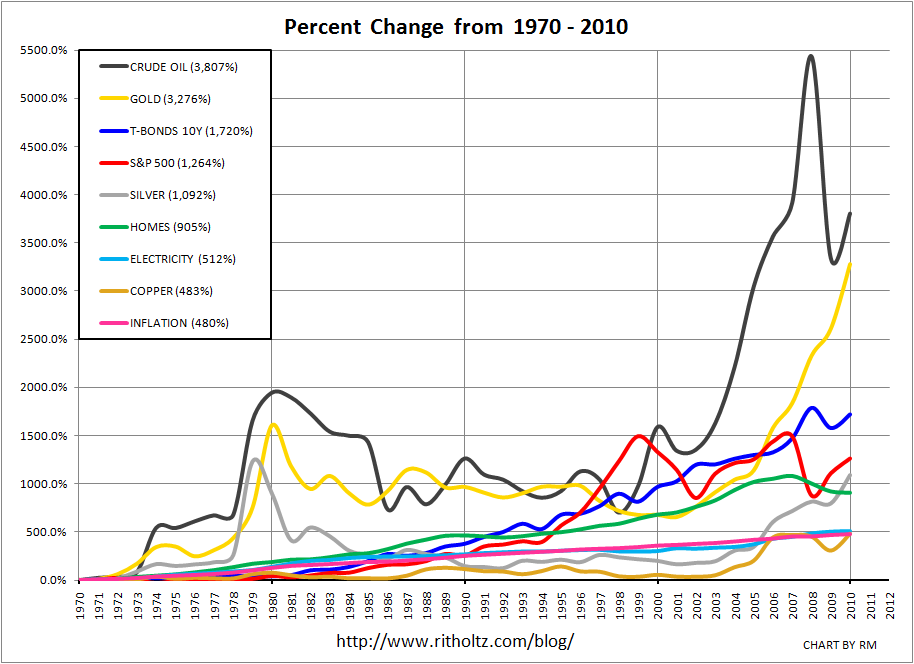

Posted: 17 Jan 2011 09:00 AM PST I find I enjoy analyzing equity markets more than any other. But as I have always said, you must always be objective when reviewing the data. And what does that data show? Stocks have not been the best performing asset class over the past 40 years. Outperformed not just by Oil and Gold, but Bonds as well. > click for larger chart  |

Posted: 17 Jan 2011 06:30 AM PST I firts showed this back in November 2008. I wanted to show it again — this time using Slideshare, a nice Powerpoint/PDF presented. My only caveat is the time period. Its one that encompasses the greatest bull market in history. I would be more interested in seeing this across multiple secular markets — say, 1946 to 2003; even 1966-1982 or 2000 might be instructive. ~~~ |

Posted: 17 Jan 2011 05:30 AM PST Bill Black is an Associate Professor of Economics and Law at the University of Missouri – Kansas City (UMKC). He was the Executive Director of the Institute for Fraud Prevention from 2005-2007. He has taught previously at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin and at Santa Clara University, where he was also the distinguished scholar in residence for insurance law and a visiting scholar at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. ~~~ The new mantra of the Republican Party is the old mantra — regulation is a “job killer.” It is certainly possible to have regulations kill jobs, and when I was a financial regulator I was a leader in cutting away many dumb requirements. But we have just experienced the epic ability of the anti-regulators to kill well over ten million jobs. Why then is there not a single word from the new House leadership about investigations to determine how the anti-regulators did their damage? Why is there no plan to investigate the fields in which inadequate regulation most endangers jobs? While we’re at it, why not investigate the areas in which inadequate regulation allows firms to maim and kill. This column addresses only financial regulation. Deregulation, desupervision, and de facto decriminalization (the three “des”) created the criminogenic environment that drove the modern U.S. financial crises. The three “des” were essential to create the epidemics of accounting control fraud that hyper-inflated the bubble that triggered the Great Recession. “Job killing” is a combination of two factors — increased job losses and decreased job creation. I’ll focus solely on private sector jobs — but the recession has also been devastating in terms of the loss of state and local governmental jobs. From 1996-2000, for example, annual private sector gross job increases rose from roughly 14 million to 16 million while annual private sector gross job losses increased from 12 to 13 million. The annual net job increases in those years, therefore, rose from two million to three million. Over that five year period, the net increase in private sector jobs was over 10 million. One common rule of thumb is that the economy needs to produce an annual net increase of about 1.5 million jobs to employ new entrants to our workforce, so the growth rate in this era was large enough to make the unemployment and poverty rates fall significantly. The Great Recession (which officially began in the third quarter of 2007) shows why the anti-regulators are the premier job killers in America. Annual private sector gross job losses rose from roughly 12.5 to a peak of 16 million and gross private sector job gains fell from approximately 13 to 10 million. As late as March 2010, after the official end of the Great Recession, the annualized net job loss in the private sector was approximately three million (that job loss has now turned around, but the increases are far too small). Again, we need net gains of roughly 1.5 million jobs to accommodate new workers, so the total net job losses plus the loss of essential job growth was well over 10 million during the Great Recession. These numbers, again, do not include the large job losses of state and local government workers, the dramatic rise in underemployment, the sharp rise in far longer-term unemployment, and the salary/wage (and job satisfaction) losses that many workers had to take to find a new, typically inferior, job after they lost their job. It also ignores the rise in poverty, particularly the scandalous increase in children living in poverty. The Great Recession was triggered by the collapse of the real estate bubble epidemic of mortgage fraud by lenders that hyper-inflated that bubble. That epidemic could not have happened without the appointment of anti-regulators to key leadership positions. The epidemic of mortgage fraud was centered on loans that the lending industry (behind closed doors) referred to as “liar’s” loans — so any regulatory leader who was not an anti-regulatory ideologue would (as we did in the early 1990s during the first wave of liar’s loans in California) have ordered banks not to make these pervasively fraudulent loans. One of the problems was the existence of a “regulatory black hole” — most of the nonprime loans were made by lenders not regulated by the federal government. That black hole, however, conceals two broader federal anti-regulatory problems. The federal regulators actively made the black hole more severe by preempting state efforts to protect the public from predatory and fraudulent loans. Greenspan and Bernanke are particularly culpable. In addition to joining the jihad state regulation, the Fed had unique federal regulatory authority under HOEPA (enacted in 1994) to fill the black hole and regulate any housing lender (authority that Bernanke finally used, after liar’s loans had ended, in response to Congressional criticism). The Fed also had direct evidence of the frauds and abuses in nonprime lending because Congress mandated that the Fed hold hearings on predatory lending. The S&L debacle, the Enron era frauds, and the current crisis were all driven by accounting control fraud. The three “des” are critical factors in creating the criminogenic environments that drive these epidemics of accounting control fraud. The regulators are the “cops on the beat” when it comes to stopping accounting control fraud. If they are made ineffective by the three “des” then cheaters gain a competitive advantage over honest firms. This makes markets perverse and causes recurrent crises. From roughly 1999 to the present, three administrations have displayed hostility to vigorous regulation and have appointed regulatory leaders largely on the basis of their opposition to vigorous regulation. When these administrations occasionally blundered and appointed, or inherited, regulatory leaders that believed in regulating the administration attacked the regulators. In the financial regulatory sphere, recent examples include Arthur Levitt and William Donaldson (SEC), Brooksley Born (CFTC), and Sheila Bair (FDIC). Similarly, the bankers used Congress to extort the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) into trashing the accounting rules so that the banks no longer had to recognize their losses. The twin purposes of that bit of successful thuggery were to evade the mandate of the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) law and to allow banks to pretend that they were solvent and profitable so that they could continue to pay enormous bonuses to their senior officials based on the fictional “income” and “net worth” produced by the scam accounting. (Not recognizing one’s losses increases dollar-for-dollar reported, but fictional, net worth and gross income.) When members of Congress (mostly Democrats) sought to intimidate us into not taking enforcement actions against the fraudulent S&Ls we blew the whistle. Congress investigated Speaker Wright and the “Keating Five” in response. I testified in both investigations. Why is the new House leadership announcing its intent to give a free pass to the accounting control frauds, their political patrons, and the anti-regulators that created the criminogenic environment that hyper-inflated the financial bubble that triggered the Great Recession and caused such a loss of integrity? The anti-regulators subverted the rule of law and allowed elite frauds to loot with impunity. Why isn’t the new House leadership investigating that disgrace as one of their top priorities? Why is the new House leadership so eager to repeat the job killing mistakes of taking the regulatory cops off their beat? Bill Black is an Associate Professor of Economics and Law at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He is also a white-collar criminologist, a former senior financial regulator, a serial whistleblower, and the author of The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One. |

.

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

0 comments:

Post a Comment