The Big Picture |

- Weed Card by Garfunkel and Oates

- Podcast: Ritholtz on Radio Free Ratigan

- Spitzer on Institutional Corruption on Wall Street

- Minsky Conference “Gary Gorton” Debate

- World Gold Bug Article on WSJ Front Page

- Is a US Default Inevitable?

- Insane Japanese TV Commercial

| Weed Card by Garfunkel and Oates Posted: 22 Apr 2011 03:00 PM PDT Riki “Garfunkel” Lindhome and Kate “Oates” Micucci sing about the perils of obtaining medical marijuana in California. Featuring David Koechner. Directed by Raul B Fernandez. www.garfunkelandoates.com |

| Podcast: Ritholtz on Radio Free Ratigan Posted: 22 Apr 2011 12:54 PM PDT > This was a fun discussion about the dirty money in politics. Transcript and MP3 after the jump ~~~ TRANSCRIPT: Barry Ritholtz on Radio Free Dylan Episode 52 – Barry Ritholtz, CEO of FusionIQ, The Big Picture blog and author of Bailout Nation: How Greed and Easy Money Corruputed Wall and Shook the World Economy RUSH TRANSCRIPT DYLAN: Welcome to Episode 52 of Radio Free Dylan, joining the show today, one of my favorites on the subject of money, investment, and banking system in America, Barry Ritholtz. He's the author of "Bailout Nation: How Greed and Easy Money Corrupted Wall Street and Shook the World Economy." Check it out if you haven't already. You can also check out his blog everyday; it is sensational. It is called the Big Picture at ritholtz.com, R-I-T-H-O-L-T-Z dot com, or you can follow him on Twitter @Ritholtz. And it's nice to see you again. BARRY: Good to see you. DYLAN: Yesterday, we talked with Chris Whalen, or recently we talked to Chris Whalen who asserted that until we take a hard line on something like the debt ceiling, we will never be able to force the necessary restructuring on global debt, U.S. debt, banking reform, and all other underlying factors from the healthcare system to the wars, for that matter, until we actually call out the government or force a crisis on the government effectively to do with these things. Do you agree with that? BARRY: Well, it's a really interesting perspective, and, you know, every time I think, "Gee, I'm really getting too cynical," I speak to a buddy like Chris and realize, "Wow, I'm not even remotely." That's a viewpoint that says, "Congress is so screwed up; Washington, DC is such a debacle." The public likes being lied; they don't want to make tough decisions that we need a full-blown crisis regardless of the consequences in order to get things done. And I hope he's wrong. I understand where he's coming from. The negative ramifications of the U.S. bumping up against its debt ceiling, not being able make payments on treasuries, on notes. You know, the U.S., it has – it's called the exorbitant privilege, "the exorbitant privilege" of having the world's reserve currency. There are certain obligations that go with that along with a number of benefits. We don't make a payment; we miss something. It's not like, "All right, I'll pay Mastercard next month and I'll be caught up." You know, we already had the warning that there's a negative outlook to the U.S. as AAA. Very desirable AAA rating is only 14 of 16 countries in the world that have that. The UK was put on a negative outlook 18 months ago and then upgraded not too long ago. The problem is their upgrade was based on austerity measures, which is now about to push Finland into recession. And that seems to be the disingenuous approach that a lot of people, not Chris, but a lot of people in DC have taken. Instead of being honest with the public, it's a lot of scare tactics and the deficit is a great example of that. DYLAN: The interesting thing is Chris uses the exact same point that you just used, which is the responsibility and the privilege and the reality, however you want to characterize it, of the fact that the U.S. dollar is the trading chip by which all things on the earth moved around – BARRY: Any commodity, just everything DYLAN: whatever it is. BARRY: is measured against the dollar. DYLAN: And so his argument is because we have that advantage, because our creditors, whether it's the banks or China or anybody else or traders around the world, and I don't mean financial traders, I mean trading partners around the world, have no alternative to the dollar as it stands right now no matter what. Back to the argument that that is the leverage by which, if you look at the colossal dysfunction in the debate around healthcare, in the debate around banking, in the debate around energy, in the debate around the wars, and the debate around international, and the debate around our trade policies, that we have to take advantage of the fact that we do have effectively this "too big to fail" status as a country to say, "You know what, we will not raise the debt ceiling and we'll use the leverage of the fact that we're too big to fail to force the restructure." BARRY: Look, in the 17th century, Spain was too big to fail. They were the leading economy in the world, and they failed. And then in the 18th century, it was France, and then in the 19th century it was England and now the United Kingdom. And now the 20th century was the U.S. century, and here we are in the beginning of the 21st century. I don't think there's any nation on earth that's too big to fail. And by the way, if you look at those countries, they're in their post-Empire phase and they're doing fine. It would be healthy, at least in my opinion, to put the U.S. in the post-Empire footing. There's no reason why the U.S. defense budget has to be the equivalent of the next 20 countries in the world. That includes Russia, that includes China, that includes North Korea; combined, our defense budget is bigger than the next one. We're providing defense services to Japan, we're providing defense services to Europe. DYLAN: Germany. BARRY: Go down the list, Korea. There's just we can't afford that. DYLAN: Isn't that Chris' point? We won't deal with that problem. BARRY: I'm sympathetic with that, but at a certain point, you know, we have – I don't think we've had an honest, legitimate debate about the budget yet. It's been Populist extremism run amuck, it's been demagoguery. Let's go through defense, let's go through Social Security, let's go through Medicare. Social Security is my favorite thing to talk about in terms of deficits because it's been running at a surplus for decades and it can run for of surplus for another century. You have to raise retirement age. The retirement age that was put in place 80 years ago, you know, everybody's lifespan has gone up dramatically; that has to adjust. That's number one. Number 2, guys like you and I, we're going to get means tested, we're not going to quality for Social Security. I think we can live with that. And number three, you get capped at $106,000 and change a year. Once you hit that payroll number, you don't pay any more taxes. So the joke is Warren Buffet or Bill Gates on January 1, they're done paying into Social Security. There are some people advocating making it unlimited. Look, that's going to double, that's going to go to $250,000 and then maybe 10, 20 years from now it will go to $500,000. But you do those three things, you means test, you raise the retirement age, you take the cap. Social Security is good for centuries. DYLAN: But what do you see as the – in other words, if Chris is – let's say Chris is more a radical view which is they're not going to do Social Security, they're not going to do defense – BARRY: They have too, though. DYLAN: They're not going to do banks unless they are forced to, and the only way to force them to is this. How do you see a pass to resolution on some of those issues absent a crisis catalyst of some sort. BARRY: You know, he and I have talked about this and one of the – we had a conversation I want to say yesterday or Monday, I don't remember what day it was. It was probably Monday. And we talked about this and I was astonished at how completely and totally – this was on the Ryan Plan whose numbers were put together by the Heritage Foundation, and it turned out that they're completely full of shit. They cooked the books, they made it up, and the only reason anyone found this out is at the end of the Ryan forecast, unemployment drops to 2.8%. Unheard of, ridiculous. And when the Heritage Foundation was asked how you got to these numbers, they kind of stammered and [inaudible 07:24] and Chris and I talked about this and he says, "Now you're aware of the Washington problem, which is everybody in DC is a paid liar." And if – we're not talking about a lawyer whose job it is to zealously defend his client in court – DYLAN: Tobacco or whatever. BARRY: What we're talking about are people who you shoot sodium pentathol into them and they would say, "Oh yeah, of course there's global warming. Of course we can manage the debt. Of course these tax cuts are expensive. Of course that 2.8% is nonsense, but I'm paid to bullshit, and I make a nice living doing it, so that's what I do." And it wasn't that way several decades ago that the loyal opposition and honest and fair debate, that seems to have disappeared and I'm less cynical than Chris, I think what – DYLAN: It doesn't sound like it. BARRY: What I think – but these are just facts. You can make intelligent policy, you can't discuss this unless you have the facts in front of you. I think what resolves this is getting the dirty money out of politics. And I've come to the conclusion that the only way to do that is a constitutional amendment mandating public funding of elections and you get Goldman Sachs out of politics and you get the rest of the bankers out politics – DYLAN: And the unions and the health companies – BARRY: And you get the unions out and you get – look, there was just something from – I mentioned it in the LinkFest today, the Center for Responsible Lending said the auto dealers managed to get exempt from the financial consumer finance board so that the extra fees and add-ons and undisclosed costs to auto loans are worth $25 billion a year in their pockets from the consumers not disclosed, not – it doesn't meet any federal regulations because they're out greasing the palms. Now, this is you would think that any politician that can't get elected and on that sort of mom-and-pop Main Street issue, how can you not, and yet it manages the dirty money. So to me, to get to any of these issues, you have to get this money out of politics. And that may sound a little naïve, but everything I come back to, the bailouts, the tax cuts, the wars, all these things are only possible if you have dishonest, you know, P.J. O'Rourke called them a Parliament of Whores, and you can't improve upon that. When people will do anything for money, you end up with the sort of financial problems we have today. If you don't get the dirty money out of the system, you can't get clean policy. DYLAN: What do you think has been the barrier? Because what you just said, I think, is something that is largely easily understood. I think a kindergartner could understand that. I actually think it is largely perceived and, in many cases, believed by a huge percentage of the American people who've had even a more modest opportunity to look at these issues. And yet the Democrats, nowhere on that issue, the Republicans, nowhere on that issue, which that's not surprising because they're on the take, they're the whores that we were referring to. BARRY: That's right. DYLAN: But, also we are not seeing outside activists – I spend a lot of time talking about it; a couple of other folks do. But you don't see the mainstream media saying the root of our evil is this, whether it's Fox, MSNBC, or anybody else. You don't see the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal saying the reason we've got this deficit, the reason we have this dysfunction, these wars, all the things you just talked about, is because of the dirty money. I think about the guy who's an alcoholic with a drinking problem and his wife has left him and he's having problems with his job and his kids don't talk to him and all these different things, and he walks around saying, "Oh, I don't know why my kids don't talk to me. I can't understand why my wife left me. I'm having a hard time at work." And people, "Oh, if you work harder, maybe if you're nicer to your wife," or whatever, but no one actually gets the fact that, "Hang on a second, maybe if you didn't drink a bottle of Jack Daniels every night, the problems that you're having with your wife, your job, and your children might go away," which is exactly your point. Maybe if you stopped drinking, in this case taking dirty money, everything from healthcare to defense would diminish. BARRY: And the friends in your analogy are the enablers is what the 12-step folks call it, and when you mentioned the mainstream media, NBC, Fox, the whole run, when you – all the parties that are involved in this, you know, they're grand enablers. There's an old line, and I know I'm getting this wrong, which is, "It's hard to convince a man of the truth when his livelihood depends on not believing that." And so you have an entire universe of lobbyists, you have an entire universe of companies, of both media, and at a certain point once you figure out how it's wired, how the system is wired, now you're a defender of that system because while it may not work for the country, it works for you. So if you're GE paying next to no taxes, if you're – you know, there was just an article – DYLAN: If you're a union rep who has huge advantages in healthcare for your members but only as long as the employer-based system exists – BARRY: That's right. DYLAN: Because if they get rid of the employer-based system, the union's relevance to their members and their quality healthcare goes away because all of a sudden the recruiting vehicle – BARRY: But that's been going away naturally. That's the great irony – you know, in the book, I mentioned the Chrysler bailout 1980, the big three or big two-and-a-half if we want to include Chrysler, they had a 75% market share of domestic cars sold in the U.S., of total cars sold domestically, and there was almost two million members. And here it is 30 years later, their market share has dropped way below 50% and we're down to 300,000 UAW members, between 200,000 and 300,000. So despite the bailouts and despite this, unions are no longer the force they once were. I don't get all bent out of shape about unions – DYLAN: And I'm not – I was just making the point of their impact on the healthcare situation. BARRY: Because to me they're just – they're such a relatively – right, they had an impact on the GM – DYLAN: They kept employer-based healthcare. BARRY: They had – absolutely, there's not doubt they had an impact on that. The thing that I find most disappointing about the era we live in is the lack of leadership. So there was just something on about Donald Trump talking about birthers and you know forget Trump and his hair or whatever that thing on his head is, but I want to see some adult step up and say, "Look, we have a lot of real important problems facing us; this is a nonissue," if you want – and Bobby Jindal actually came close. I'm like, "Wow, this is going to be an adult conversation," and then at the last minute he sort of back away and says, "You know I take the President at his word." No, no, no, step up and lead and say, "This is bullshit, let's talk about we still have high unemployment, we still have a tremendous amount of leverage in the system, we still have a huge housing problem, let's fix this. And if you're going to focus on that, you're wasting time and energy that could be put to better use." And, you know, the Democrats also have not really stepped up and led on a lot of these issues. It's enormously disappointing that there is no Ronald Reagan, there is no John F. Kennedy. For a moment it looked like Obama was going to possibly rise to that mantled, but that moment seems to have passed. So to me, from a political perspective, and I'm an independent; I throw rocks at both sides. It's disappointing that there's not even anybody to root for. And so, again, I try not to be cynical. DYLAN: I agree. BARRY: What Chris said I think is really cynical, "Hey, let it all blow up and we'll worry about fixing – picking up the pieces afterwards." I think Alan Greenspan, by the way, said something very serious before the – similar before the dot-com collapse in 2000, "Oh, it's easy to clean up after." I think the costs and the ramifications of cleaning up, allowing the debt ceiling to lapse, would be really, really substantial. And what happened in '95 was a drop in the bucket. It's a whole different universe today. I don't think it is even comparable. It would be really, really damaging. DYLAN: What would happen? BARRY: What would happen? All right, so the AAA rating would be put at risk, which means we're now funding a huge deficit, a huge ongoing debt, which by the way has been ballooning for three decades. This isn't anything new. This exploded and in fact, the fascinating about Reagan's era is he reduced the deficit pretty dramatically by raising taxes. You know, he had huge tax cut, especially the top rate was almost 90%, brought the way down, and then slowly brought things up in order bring in more revenue. I think he was the last serious Republican that was willing to say, "Hey, sometimes, you know, it it's not just spending; it's income also. You've got to raise –" you know, they called them revenue enhancers, taxes were a dirty word, but they actually did it. You don't see that going on anymore. And the Democrats are nearly as bad as the Republicans in terms of – I give Obama credit for saying we have to raise taxes on the highest earners. But if we were really adults, if we were going to have a mature conversation, you would look at the United States versus the rest of the western world and say, "Hey, we have amongst the lowest net taxes and yet we're spending more than everybody else; it's time for some shared sacrifice, everybody has to kick in a little more, everybody has to consume a little less in terms of government services, and that's how you get the deficit under control. This, "I don't want to cut anything and I don't want to raise taxes and let's magically fix the deficit" is silly and it's childlike and we really need to move past that. DYLAN: You referenced this earlier, the disingenuous Solution of austerity where, "Oh, we've got this big deficit, so what we'll do is we'll just cut social spending, which is a minute percentage of what our spend is to begin with, we won't address healthcare reform, we won't address a major global defense overhaul and reduction, we won't address entitlements like Social Security; we will simply reduce social spending ala England " BARRY: And Ireland, and by the way – DYLAN: What's wrong with that? BARRY: Well, first of all, if you look at those economies, they're doing really poorly. You know, the fascinating thing, this has become an anti-Keynes – John Maynard Keynes was a brilliant economist and actually stock trader in the '20s, '30s, '40, and the monetarists who rose up in opposition to him – I think a lot of people misunderstand Keynes. And what Keynes said is, "During an economic expansion, the government should be cutting spending and raising taxes and running a balanced budget." But when you go into a real bad recession, well, that's when the government should cut taxes and raise spending and substitute for the lack of government and consumer spending to sort of smooth that cycle out instead of having these high peaks and deep valleys. You're going to make it a little softer and a little easier to bear. The problem is the way it's been implemented over the past 50 years is while we increase spending and cut taxes when things were bad, but we never took it back when things were good. So no one wants to do the hard thing, and again, this is a lack of a mature conversation. The first person who started cutting spending and raising the taxes, his opponents would go crazy on him and that person would never get reelected again. So all we have are people who increase spending and cut taxes but never do anything to legitimately balance the budget. Forget NPR or Planned Parenthood, that's 1/1000th of a percent of the overall budget. You know, what John Dillinger said is he robs banks because that's where the money is. So in order to balance the budget, you have to raise taxes, because that's where the money is, you have to cut the defense spending, you have to cut Social Security, you have to cut Medicare, but do it in a way that makes sense, and we haven't had that conversation yet. DYLAN: You write wonderfully on a regular basis on your blog, the Big Picture at ritholtz.com. Among some of your recent posts, you talk about Europe's relationship with the banks and bailout relative to our own, and I want to read a little bit of this to the folks. You say, "In nations where bankers and their creditors were allowed to go belly up, the populace seems to be more satisfied with the outcome, and the politicians are mostly managing to retain their jobs. Tiny Iceland seems to be the only country that got this right," and then you get into how Iceland obviously did a debt restructuring. Europeans are slowly figuring your right, that they got royally screwed by bankers, assuming bank debt, taking responsibility for bankers recklessness is simply not in the public's interest. I wonder when American will reach the same conclusion. Don't you think Americans have largely reached this conclusion? Maybe our politicians and our media has not. BARRY: I'm not sure. I'm not sure. I go back and forth on this. You know, for a brief moment when the Tea Party first erupted, I thought that was a huge pushback against the bailout. DYLAN: Me, too. BARRY: And then somehow they got Jiu-Jitsu'd and it became something else entirely. DYLAN: [cross-talking 20:32] BARRY: I guess. And, you know, whatever your perspective on gay rights are, clearly it had nothing to do with the crisis, the financial crisis, and it has nothing to do with fixing – although some people in California have argued that if you legalize gay marriage it would cause a surge of economic activity, but the reality is – DYLAN: Household formation in San Francisco. BARRY: Yeah, it's – but the reality is there was this glimmer and it was just completely derailed. And, you know, the Democrats and the Republicans jointly are part of the problem. I was hoping that that was – DYLAN: But that doesn't speak to the people. In other words, do you believe that the people – I mean this is obviously conjecture on our part, but do you believe that – you're asserting that the people of Iceland, that the people of Western Europe – BARRY: And Ireland, and Norway. DYLAN: – and all the rest of it understand that the bankers screwed them, that they're running a scam, and they're not going to tolerate it, that the bank is there to serve the economy, that the country is not there to serve the banks. BARRY: There's a very different political debate that takes place in Europe. First of all, it's a much older society than the United States, so it's a little more mature. What I've found – you know, I was always taught that you never discussed religion or politics in the United States. In Europe, you could sit down with people of opposite political views and everybody will agree, at least more or less on the same facts, and the debate is more on philosophy and theory and if we do this, this will happen, no, if we do this, that will happen, and it's just far more cosmopolitan and sophisticated than the crazy – DYLAN: Fear-mongering. BARRY: Yeah. Can I tell you something? I get emails everyday, you know, the Jews caused the credit crisis. I get that stuff constantly. And before that, I used to get my all-time favorite comment is an unspeakable word cause the credit crisis that came up on the blog. And it's easy enough to screen that stuff out and not have it show up, but that's the level of discourse. And in Europe, those are Arian extremists that aren't part of the political debate. The debate, the conversations, the discussion is just a whole different level of sophistication. It's very buzzword, bumper sticker based. There isn't a lot of independent thought. You know, talk radio and talk television drive a ton of the conversation. I used to just see the same emails, it's phrased ever so slightly different, over and over from different people, and it's clear someone heard something that may or may not have been true, they repeated it and it was comforting for them so these things sort of went viral. You know, there's a positive side to intelligence spreading through the internet, and the negative side is dumb things seem to find a home, and especially if there's a cute buzzword involved, catch on. And so you get just mad, insane, foolishness, and – DYLAN: Does this not get us back to Chris Whalen? Because of all these things, we must – or does it make your point which is you better not create a crisis because you have such a stupid or unsophisticated political debate that if you create a crisis, you'll get a solution that is the worst solution you could every imagine because it will be the Jews fault, or whatever. In other words, instead of actually – the crisis, instead of catalyzing the sort of debate you just discussed in Europe, will catalyze a madness. BARRY: By the way, I don't think the Europeans are any smarter than the Americans in general. I think the extremists in America seem to have found a certain resonance and are louder than their numbers suggest. So I want to make it clear, it's not that Europeans are smarter or more mature than Americans, they've just over the years learned how to do the sort of debate, and look, World War II was fought on their front porch, so they've learned how to deal with the real crazies, and they marginalize the extremists. In the United States, we don't marginalize extremists; they're right there at the table with everybody else. So to go to Chris, look, I think Chris' analysis is thoughtful, I just haven't reach the point of maximum cynicism where I say, "You know, you've got to crash the bus off the cliff before we can rebuild it." And that's kind of the argument he's making is if you don't throw the whole system out of whack you'll never be able to rebuild this. But that goes back to the dirty money. So let's say he's right. Let's say we crash through debt ceiling, everything falls apart, so what are we going to have? It's going to be put together by Goldman Sachs and Citigroup and – DYLAN: Health insurers. BARRY: Right. Look at who's controlling D.C. That's not the group I'm willing to have rebuild the system, especially since they were so opportunistic and did such a great job during the crisis. You know, the same people who captured trillions of dollars from the government are very likely to put together a system that is a corporatocracy, not a democracy. It's a government for the corporation, not for the people, and that's my concern. Until you fix campaign finance, the people at the controls just aren't trustworthy. They're being sold to the highest bidder so why do I want to wreck the system and let AIG and Goldman rebuild it. That's not to your or my advantage. That's not to 99% of the public's advantage. DYLAN: Barry Ritholtz, the Big Picture is the blog, ritholtz.com, on Twitter at ritholtz, R-I-T-H-O-L-T-Z, and, again, the book, "Bailout Nation: How Greed and Easy Money Corrupted Wall Street and Shook the World Economy." It's always a pleasure, Barry. Thank you. BARRY: Thanks for having me. DYLAN: And we'll be back right after this. DYLAN: Welcome back to Radio Free Dylan. I want to leave you with one more comment from Barry because I think it's incredibly relevant and necessary to understand what is going on here. And Barry references an old market strategist, Art Cashin who works at UBS, and it goes like this. He says, "UBS's Art Cashin directs us to the economist Buttonwood column for an interesting take after the S&P downgrade. The debt in our system, going back to 2008 or beyond, has not been eliminated, and has merely been moved from the banks to the taxpayer. It's three years since Bear Stearns was pushed into the arms of JPMorgan and the fundamental debt problem hasn't been resolved. The debt has been moved around, but not eliminated. This is undoubtedly bought time, and I quite understand the point made frequently by my colleague, that government and central banks have acted to protect workers from losing their jobs and to prevent consumption from collapsing. In this, they have had a fair degree of success. But the debt is still there. It must either be eliminated by growth, inflation, the devaluation of our currency, or default. The U.S. has better growth prospects than most European nations and has the exorbitant privilege (as Barry said earlier) of issuing debt in the world's reserve currency, which keeps its cost down. But it resembles one of those Greek myths when the hero's power is accompanied by a curse, in this case a political system that is not designed for serious deficit cutting, a point made by S&P." I thank you for listening to us today and spending some of your day with me. It's a privilege to have that opportunity. My name is Dylan Ratigan and that will do it for Radio Free Dylan today and we'll talk to you next time. http://www.dylanratigan.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/RFD-Ep-52-Barry-Ritholtz2.mp3 This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Spitzer on Institutional Corruption on Wall Street Posted: 22 Apr 2011 09:30 AM PDT Harvard University Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics |

| Minsky Conference “Gary Gorton” Debate Posted: 22 Apr 2011 09:00 AM PDT Last week, the Levy Economics Institute hosted the 20th Annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference, a wonkish discussion on all things Hyman Minsky. This year’s focus was on Financial Reform and the Real Economy. For those of you who are not academic economists, Professor Hyman Minsky argued that stability eventually leads to instability. The stable economic backdrop causes people to become complacent and take on more risks than they might during riskier times. For some background, see this discussion on Minsky by Prof. Steve Mihm. You can see our earlier guest posts on the Minsky Conference here and here. The purpose of the Minsky Conference was to “address the ongoing effects of the global financial crisis on the real economy, and examine proposed and recently enacted policy responses. Should ending too-big-to-fail be the cornerstone of reform? Do the markets' pursuit of self-interest generate real societal benefits? Is financial sector growth actually good for the real economy? Will the recently passed US financial reform bill make the entire financial system, not only the banks, safer?” I was unable to attend, but several colleagues not only went, but reported back what they saw. The following discussion was art of a longer email thread on some of the emails; it is reproduced here with the permission of the authors. ~~~ Steve Waldman (Interfluidity) writes about the original updates: I find little to disagree with in your note, except that I find little resemblance between what you say and what I heard in Gorton’s speech. You write “His key observation is that what is gained by having the Fed and other policymakers guarantee bank liabilities –- namely, financial stability –- is lost through the ensuing complacency which tends to spawn longer, more damaging crises.” That’s just not what I took from the speech. What I heard was quite the opposite, that the crisis was basically a result of the financial system having evolved means of duration-mismatched finance that were NOT guaranteed, and that therefore the liquidity crises endemic to the system pre-Fed/FDIC had returned. Gorton carefully avoided making specific policy recommendations, preferring instead to shelter in his self-aggrandizing evidence fetish and putting all hope in Dodd Frank’s Office of Financial Research. But it seems to me that the clear implication of Gorton’s story — which described the crisis as an old-fashioned, individually rational but collectively destructive bank run — is to guarantee the shadow banking system. I heard nothing of a critique of, say, FDIC in his speech. (Gorton did point out that FDIC was something of a policy accident. Neither FDR nor the banks initially supported deposit guarantees but popular support forced Congress to act. But my sense was that he took this to be a happy accident, that despite an odd process we had stumbled into good policy.) If you think the crisis was a run on the shadow banking system, AND you think that the sponsors and guarantors of the shadow banking system actually did an okay job in underwriting, AND you think that the right way to prevent “sunspot” bank runs is with deposit guarantees, then the logical policy response is to guarantee the shadow banking system, and not to worry so much about regulating or holding to account sponsors and guarantors, since market forces have in fact proven sufficient to enforce good-enough behavior. This is almost a syllogism. Gorton set up all three assumptions quite explicitly. That he didn’t state the conclusion was rhetorically savvy, but doesn’t alter the implicit recommendation. And yet what you heard was almost precisely opposite to what I heard. You see Gorton’s speech as a criticism of complacency due to guarantees, as a warning about moral hazard. I heard Gorton explicitly mock people for “jumping” to moral hazard as an explanation without “evidence”. Maybe I misheard, and your description is a better characterization of Gorton’s view than my own. If I’m going to write so much about it, maybe I should give the speech another listen. Perhaps others can weigh on with their recollections. I like your suggestion that lender of last resort activity should be provided, but carefully rationed to parties relatively distant from poor decisionmaking like money market funds, and that more comprehensive guarantees as were provided to several of the larger banks should be explicit and accountable rather than implicit and deniable, as they were via the “no more Lehmans / SCAP” approach. I wish I had heard Gary Gorton use his considerable intellect and rhetorical skill to make that case. But that is not at all what I heard. -SW Note: There is an alternative policy recommendation consistent with Gorton’s set-up. Rather expanding guarantees to the shadow banking system, one could argue that duration-mismatched liquidity provision should be forced back onto the balance sheets of existing regulated and guaranteed institutions. Since Gorton’s account is consistent with this policy regime as well, I’ve overstated my case a bit in claiming that support of expanded guarantees was implied. The story Gorton tells implies either an expansion of guarantees to the shadow banking system, or banning the shadow banking system in favor of a remigration to bank balance sheets. I have a guess as to which of these options Gorton would prefer, but since he did not offer actual policy advice, I could be mistaken. However, neither option challenges the practice of guaranteeing duration mismatched liabilities, which practice I think that Andrew would like us to examine more critically (and I’d enthusiastically agree with Andrew on that). ~~~~ Did you hear Gorton yday? I thought he was 1/4 right and 3/4 downright loony. 17bps of losses? The crisis had nothing to do with prop trading? How did no one challenge him on any of this? I think that’s exactly right. Gorton tells an important story in his description of runs/liquidity crises that are out of line with the magnitude of any specific shock. But I thought his useful contribution was overwhelmed by the very Orwellian way in which his talk was framed. Gorton is not content to describe an important piece of the crisis. He instead tried to make it the whole explanation of the crisis. That is not accurate. In particular, Gorton mocks the important degree to which the crisis was a matter of ex ante insolvency. That is, he pretends it was only a “panic” so that ultimately, banks did nothing wrong and governments would have lost nothing if they had fully insured and guaranteed bank assets. The most Orwellian bit was the panegyric to the importance of “evidence” in economics. He described basically all commentators other than himself as know-nothings — “journalists” who couldn’t possibly understand, economists who’d never heard of CDOs suddenly calling themselves experts, etc. He talked about the importance of data. And then he rose above his caricature of everybody else by offering up that all-important data, in the form of a single cherry-picked statistic. Rhetorically, he invited his audience to rise above the noise of all the know-nothings and join him in understanding his true scientific, evidence-based account. I thought his statistic was 71 bps, but maybe it was 17 bps as you say. (I’m writing this from memory; I’ve little inclination to relive or relisten to the speech.) That difference doesn’t matter. The point is that he described the losses as trivial. That is a terrible lie. Let’s unpack why. First of all, this statistic was realized losses on AAA tranches of subprime RMBS. Someone in the audience did try to call him on “realized”. Gorton mocked the gentleman by simply repeating “realized” in a tone intended to suggest that the interruption was ridiculous, and then moved on. The word “realized” renders Gorton’s statistic very misleading. Losses are generally realized on securities when they are sold or at maturity. Many, perhaps the majority, of AAA tranches on subprime RMBS have not been traded post-crisis, but have remained on the balance sheets of the banks that held them before the storm. So, “realized” losses may dramatically underrepresent economic losses. But that’s not all. Restriction of consideration to AAA subprime RMBS ignores a lot of losses, including losses on AAA securities that holders were not prepared to handle. A substantial fraction of an RMBS (usually between 5% and 20% of their value) was not AAA. Much of this non-AAA portion was mezzanine, not equity, and was itself recycled into CDOs or CDO-like securities, whose AAA portions took huge losses. So the economic losses on these deals might have been as high as about 15% [1500 bps!] before any AAA tranches of subprime RMBS would be impacted at all. Much of that value would have become losses to banks holding senior and “supersenior” tranches of CDOs. Also, as you’ve done a lot of work documenting, these mezzanine tranches of RMBS were often placed in the reference portfolio of synthetic CDOs, magnifying the potential exposures of banks and/or bond insurers, who often bore the risk of senior tranches of these deals. [Gorton doesn't tell us whether his loss statistic on plain RMBS losses incorporates or fails to incorporate reimbursements from insurers, whether so-called "monoline" insurers or other counterparties who wrote protection in the form of a CDS or similar agreement. If his loss statistic is net of reimbursements, then it ignores payouts made by insurers and other protection writers, who in general were themselves systemically important financial institutions.] Finally, Gorton ignores the impact of government stabilization on the scale of losses realized in these securities. By government stabilization, I don’t mean the lender-of-last-resort activities that will ostentatiously be paid off without apparent losses to the public. By stabilization, I mean the massive deficit spending that has caused the US fiscal position to deteriorate by more than $4T over the past few years, increasing the total stock of Federal government debt by more than 40% and the stock of Federal debt held by the public by about 80% (since August 2007). If the government had held deficit expenditures constant, or limited them to at most the worst pre-crisis deficits (as a fraction of GDP) experienced over the past decade, losses on these securities would have multiplied dramatically. If this had truly been just a liquidity panic, as Gorton suggests, lender of last resort interventions would have been sufficient, and repayment of the TARP and Fed vehicles would have left the government balance sheet unimpaired (relative to prior projections) after that support was recovered. Yet even after TARP etc is paid back, the United States will still find itself several trillion dollars poorer than would have been projected in, say, 2006. Gorton might argue that the Treasury’s losses were due to behavioral changes resulting from the public’s panic, that if the government had offered support earlier and unconditionally no panic would have occurred and no long-term deterioration of the balance sheet would have occurred. That’s an untestable counterfactual, so it cannot entirely be ruled out. But it’s pretty implausible. Fundamentally, the losses on RMBS and compilations & derivatives thereof are driven by losses on the value of the assets that secured them. If you really want to believe this was only a liquidity panic, you have to believe that there was no housing bubble, that housing prices would also have been sustainable had the government offered support sufficient to prevent the public from perceiving the hiccup. But home prices had been falling dramatically well before the financial panic occurred. I suppose you could believe that, absent a panic, defaults would not have occurred even despite falling housing prices, because borrowers would have eaten the losses and thereby sheltered the banks. Again, that strikes me as implausible. Note that I don’t mean to say that Gorton’s liquidity run story is wrong, or that it is unimportant. On the contrary, it is right and represents a very important piece of what occurred. But Gorton manipulatively augments the story with a framing designed to suggest that this was _just_ a liquidity panic, that at worst the financial sector failed to manage liquidity adequately but that its lending and underwriting practices were ultimately not a big problem. There was, he suggested quite explicitly in his talk, no major problem of agency costs and moral hazard. (He describes those as stories that no-nothings jumped to without evidence.) Therefore, he absolves the financial sector of nearly all culpability. But his premise is untrue — this was a deep and serious solvency crisis that has been remedied only through massive government support. Gorton has written quite a lot, and I’ve read only a bit of his work. Perhaps he has tried to address my concerns elsewhere. But standing on its own, despite a lot of insight and even some brilliance, Gorton’s speech was at best poorly argued. I hate to be uncharitable, but I already have been and I’ll stick with that. The talk struck me not only as weak due to constraints of time or format, but as purposefully manipulative. ~~~ Scott Frew responds: Satyajit Das in a review of Michael Lewitt’s Death of Capital on nakedcapitalism makes the argument you seem to want to make against Gorton, Andrew. In particular, paragraph 3 below. http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/04/satyajit-das-dead-hand-of-economics.html In “The Death of Capital”, Michael Lewitt, an investment professional and editor of the HCM Market Letter, explores the ultimate effect of “zombie economics”. Mr. Lewitt’s thesis focuses on the outcome of these economics, in particular, the rise of financialisation, debt and speculation and its effect on the real economy. “The Death of Capital” is robust in its arguments, especially in it denunciation of Wall Street practices which he views as unproductive and morally reprehensible. The book makes the case that financialisation ultimately has the effect of undermining the fundamental role of capital in societies and financial markets as a mechanism for saving and channelling funds into real businesses. Drawing heavily on the work of Adam Smith, Karl Marx, Keynes and Hyman Minsky, Mr. Lewitt outlines his thesis clearly. His solution seems curious, in the light of the trajectory of his critical argument – greater regulation, imposition of a tax on speculative transactions (in effect, a Tobin tax) and “principle based” reform. It is unclear why the proposed reforms can or will work, given that the very forces that propelled the financialisation that Mr. Lewitt criticises would be charged with implementing them. As Scottish philosopher David Hume knew: “All plans of government, which suppose great reformation in the manners of mankind, are plainly imaginary.” The reality is that economics and economic relations are an adjunct to a larger process – the process of broad social control. Marx wrote about the fetishism of money, arguing that “the money-form of the world of commodities … actually conceals, instead of disclosing the social character of private labour, and the social relations between individual producers”. Human beings and societies are unable to see their own products and social relationships for what they are and become slaves to powerful forces. ~~~ Rajiv Sethi adds: Steve and I have been discussing the Gorton speech at length, first at Here, in a nutshell, is my response. Gorton really must have known that As Perry Mehrling has recently noted, the original mandate of the Here are links to Perry’s post, and my response: http://ineteconomics.org/blog/money-view/the-new-federal-reserve http://rajivsethi.blogspot.com/2011/01/original-mandate-of-federal-reserve.html Finally, Andrew, I’m not sure where you got the idea that Minsky was http://rajivsethi.blogspot.com/2009/12/economics-of-hyman-minsky.html Thanks to all of you for copying me on this interesting discussion. Rajiv ~~~ Steve Waldman: Rajiv and I have had a side conversation on this. Rajiv is a person of unusually generous spirit, and was willing to contemplate the possibility that Gorton is simply so self-assured that what seemed manipulative was natural and unconscious. I felt compelled to defend my nastiness. Rajiv also pointed to a quite interesting piece by Gorton on the CDS market and the informational efficiency of bond pricing, which asked the provocative question of whether we might not want bond markets to be so informationally efficient, in the same way as we might not want medical insurance markets capable of discriminating between good and bad risks ex ante. Though I’d ultimately answer “no”, that we want informationally efficient bond markets, I found the piece very useful and thought-provoking. When he’s not acting as a sly advocate for certain causes, Gorton is a brilliant guy with a lot to contribute. ~~~ 20th Annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference on the State of the US and World Economies |

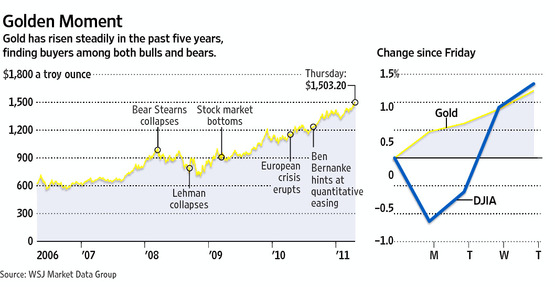

| World Gold Bug Article on WSJ Front Page Posted: 22 Apr 2011 06:01 AM PDT Front page WSJ story today — World Is Bitten by the Gold Bug:

Front page stories are not great usually for investments — although this is the WSJ, not Time or Newsweek. It has much less of a contrarian indication. > > Update: I see this was also in the Guardian this week: > Source: |

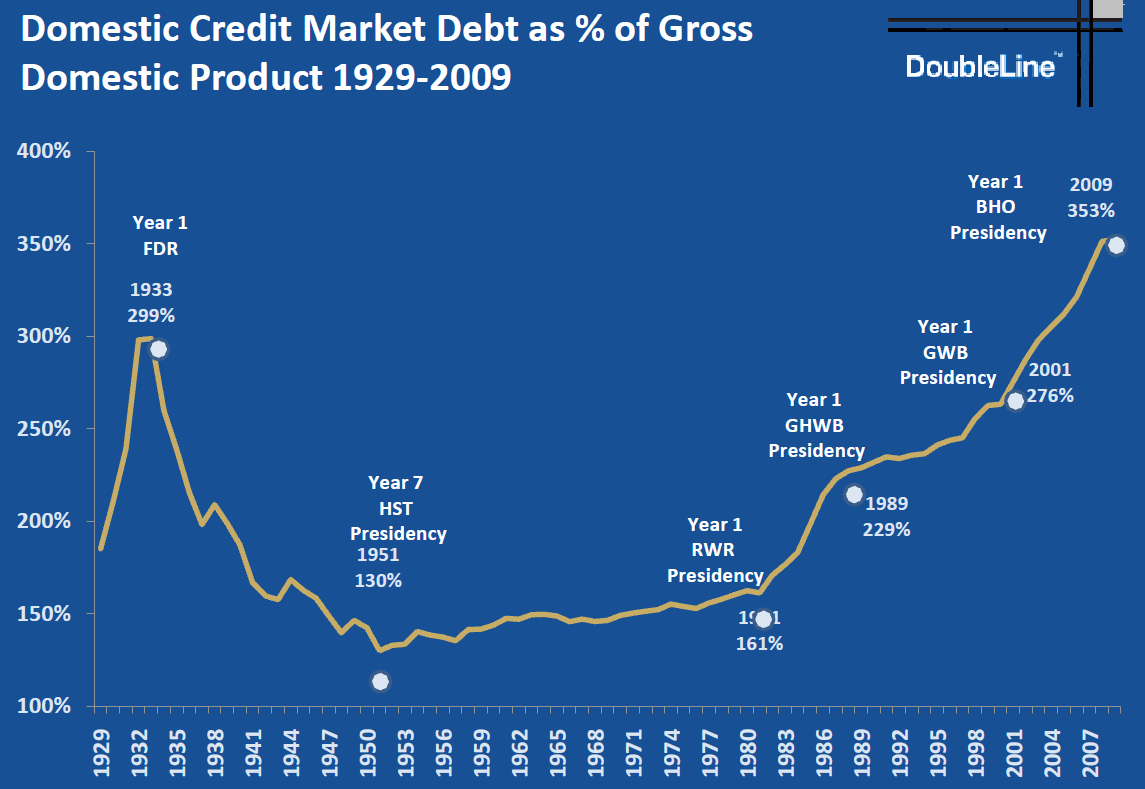

| Posted: 22 Apr 2011 05:30 AM PDT Pragmatic Capitalism ran this last July– while I don’t agree with it, I do find it thought provoking: Download: Jeff Gundlach’s Guide To Inevitable American Default JEFF GUNDLACH SAYS THE USA WILL DEFAULT |

| Posted: 22 Apr 2011 04:18 AM PDT Wait until you see what it is actually for. Madness. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

0 comments:

Post a Comment