The Big Picture |

- Governor Jeremy C. Stein Comments on Monetary Policy

- Saturday Night Cinema: The Sound of Monsters University

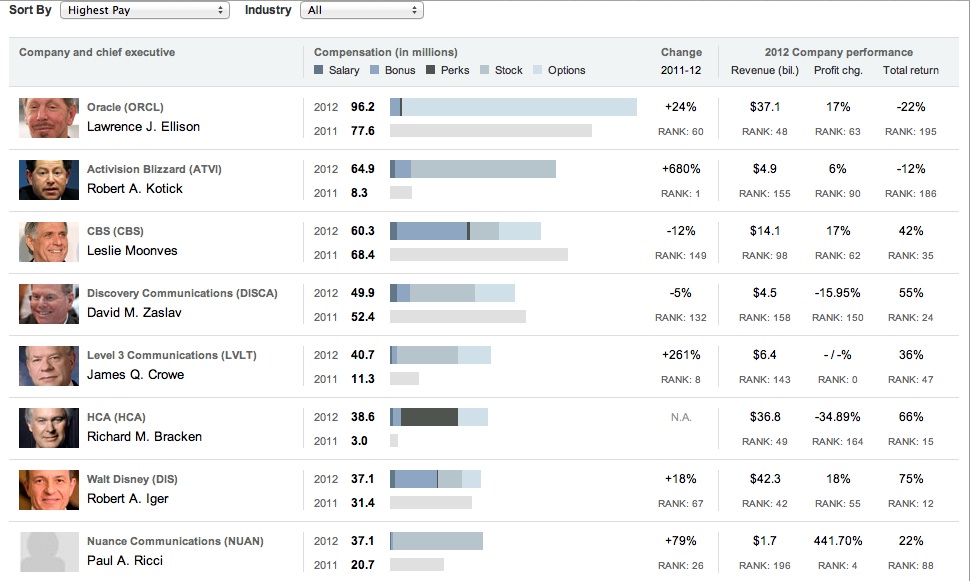

- Executive Pay by the Numbers

- Readers push back: “Missed the rally & still fighting the tape”

- 10 Weekend Reads

- Ferrari 250 GT Zagato Sanction II

| Governor Jeremy C. Stein Comments on Monetary Policy Posted: 07 Jul 2013 02:00 AM PDT Governor Jeremy C. Stein Comments on Monetary Policy

Thank you very much. It’s a pleasure for me to be here at the Council on Foreign Relations, and I look forward to our conversation. To get things going, I thought I would start with some brief remarks on the current state of play in monetary policy. As you know, at the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting last week, we opted to keep our asset purchase program running at the rate of $85 billion per month. But there has been much discussion about recent changes in our communication, both in the formal FOMC statement, as well as in Chairman Bernanke’s post-meeting press conference. I’d like to offer my take on these changes, as well as my thoughts on where we might go from here. But before doing so, let me note that I am speaking for myself, and that my views are not necessarily shared by my colleagues on the FOMC. It’s useful to start by discussing the initial design and conception of this round of asset purchases. Two features of the program are noteworthy. The first is its flow-based, state-contingent nature–the notion that we intend to continue with purchases until the outlook for the labor market has improved substantially in a context of price stability. The second is the fact that–in contrast to our forward guidance for the federal funds rate–we chose at the outset of the program not to articulate what “substantial improvement” means with a specific numerical threshold. So while the program is meant to be data-dependent, we did not spell out the nature of this data-dependence in a formulaic way. To be clear, I think that this choice made a lot of sense, particularly at the outset of the program. Back in September it would have been hard to predict how long it might take to reach any fixed labor market milestone, and hence how large a balance sheet we would have accumulated along the way to that milestone. Given the uncertainty regarding the costs of an expanding balance sheet, it seemed prudent to preserve some flexibility. Of course, the flip side of this flexibility is that it entailed providing less- concrete information to market participants about our reaction function for asset purchases. Where do we stand now, nine months into the program? With respect to the economic fundamentals, both the current state of the labor market, as well as the outlook, have improved since September 2012. Back then, the unemployment rate was 8.1percent and nonfarm payrolls were reported to have increased at a monthly rate of 97,000 over the prior six months; today, those figures are 7.6 percent and 194,000, respectively. Back then, FOMC participants were forecasting unemployment rates around 7-3/4 percent and 7 percent for year-end 2013 and 2014, respectively, in our Summary of Economic Projections; as of the June 2013 round, these forecasts have been revised down roughly 1/2 percentage point each. While it is difficult to determine precisely, I believe that our asset purchases since September have supported this improvement. For example, some of the brightest spots in recent months have been sectors that traditionally respond to monetary accommodation, such as housing and autos. Although asset purchases also bring with them various costs and risks–and I have been particularly concerned about risks relating to financial stability–thus far I would judge that they have passed the cost-benefit test. However, this very progress has brought communications challenges to the fore, since the further down the road we get, the more information the market demands about the conditions that would lead us to reduce and eventually end our purchases. This imperative for clarity provides the backdrop against which our current messaging should be interpreted. In particular, I view Chairman Bernanke’s remarks at his press conference–in which he suggested that if the economy progresses generally as we anticipate then the asset purchase program might be expected to wrap up when unemployment falls to the 7 percent range–as an effort to put more specificity around the heretofore less well-defined notion of “substantial progress.” It is important to stress that this added clarity is not a statement of unconditional optimism, nor does it represent a departure from the basic data-dependent philosophy of the asset purchase program. Rather, it involves a subtler change in how data-dependence is implemented–a greater willingness to spell out what the Committee is looking for, as opposed to a “we’ll know it when we see it” approach. As time passes and we make progress toward our objectives, the balance of the tradeoff between flexibility and specificity in articulating these objectives shifts. It would have been difficult for the Committee to put forward a 7 percent unemployment goal when the current program started and unemployment was 8.1 percent; this would have involved a lot of uncertainty about the magnitude of asset purchases required to reach this goal. However, as we get closer to our goals, the balance sheet uncertainty becomes more manageable–at the same time that the market’s demand for specificity goes up. In addition to guidance about the ultimate completion of the program, market participants are also eager to know about the conditions that will govern interim adjustments to the pace of purchases. Here too, it makes sense for decisions to be data-dependent. However, a key point is that as we approach an FOMC meeting where an adjustment decision looms, it is appropriate to give relatively heavy weight to the accumulated stock of progress toward our labor market objective and to not be excessively sensitive to the sort of near-term momentum captured by, for example, the last payroll number that comes in just before the meeting. In part, this principle just reflects sound statistical inference–one doesn’t want to put too much weight on one or two noisy observations. But there is more to it than that. Not only do FOMC actions shape market expectations, but the converse is true as well: Market expectations influence FOMC actions. It is difficult for the Committee to take an action at any meeting that is wholly unanticipated because we don’t want to create undue market volatility. However, when there is a two-way feedback between financial conditions and FOMC actions, an initial perception that noisy recent data play a central role in the policy process can become somewhat self-fulfilling and can itself be the cause of extraneous volatility in asset prices. Thus both in an effort to make reliable judgments about the state of the economy, as well as to reduce the possibility of an undesirable feedback loop, the best approach is for the Committee to be clear that in making a decision in, say, September, it will give primary weight to the large stock of news that has accumulated since the inception of the program and will not be unduly influenced by whatever data releases arrive in the few weeks before the meeting–as salient as these releases may appear to be to market participants. I should emphasize that this would not mean abandoning the premise that the program as a whole should be both data-dependent and forward looking. Even if a data release from early September does not exert a strong influence on the decision to make an adjustment at the September meeting, that release will remain relevant for future decisions. If the news is bad, and it is confirmed by further bad news in October and November, this would suggest that the 7 percent unemployment goal is likely to be further away, and the remainder of the program would be extended accordingly. In sum, I believe that effective communication for us at this stage involves the following key principles: (1) reaffirming the data-dependence of the asset purchase program, (2) giving more clarity on the type of data that will determine the endpoint of the program, as the Chairman did in his discussion of the unemployment goal, and (3) basing interim adjustments to the pace of purchases at any meeting primarily on the accumulated progress toward our goals and not overemphasizing the most recent momentum in the data. I have been focusing thus far on our efforts to enhance communications about asset purchases. With respect to our guidance on the path of the federal funds rate, we have had explicit links to economic outcomes since last December, and we reaffirmed this guidance at our most recent meeting. Specifically, we continue to have a 6.5 percent unemployment threshold for beginning to consider a first increase in the federal funds rate. As we have emphasized, the threshold nature of this forward guidance embodies further flexibility to react to incoming data. If, for example, inflation readings continue to be on the soft side, we will have greater scope for keeping the funds rate at its effective lower bound even beyond the point when unemployment drops below 6.5percent. Of course, there are limits to how much even good communication can do to limit market volatility, especially at times like these. At best, we can help market participants to understand how we will make decisions about the policy fundamentals that the FOMC controls–the path of future short-term policy rates and the total stock of long-term securities that we ultimately plan to accumulate via our asset purchases. Yet as research has repeatedly demonstrated, these sorts of fundamentals only explain a small part of the variation in the prices of assets such as equities, long-term Treasury securities, and corporate bonds. The bulk of the variation comes from what finance academics call “changes in discount rates,” which is a fancy way of saying the non-fundamental stuff that we don’t understand very well–and which can include changes in either investor sentiment or risk aversion, price movements due to forced selling by either levered investors or convexity hedgers, and a variety of other effects that fall under the broad heading of internal market dynamics. This observation reminds us that it often doesn’t make sense to try to explain a large movement in asset prices by looking for a correspondingly large change in expectations about economic fundamentals. So while we have seen very significant increases in long-term Treasury yields since the FOMC meeting, I think it is a mistake to infer from these movements that there must have been an equivalently big change in monetary policy fundamentals. Nothing we have said suggests a change in our reaction function for the path of the short-term policy rate, and my sense is that our sharpened guidance on the duration of the asset purchase program also leaves us close to where market expectations–as expressed, for example, in various surveys that we monitor–were beforehand. I don’t in any way mean to say that the large market movements that we have seen in the past couple of weeks are inconsequential or can be dismissed as mere noise. To the contrary, they potentially have much to teach us about the dynamics of financial markets and how these dynamics are influenced by changes in our communications strategy. My only point is that consumers and businesses who look to asset prices for clues about the future stance of monetary policy should take care not to over-interpret these movements. We have attempted in recent weeks to provide more clarity about the nature of our policy reaction function, but I view the fundamentals of our underlying policy stance as broadly unchanged. Thank you. I look forward to your questions. ~~~ Other Formats |

| Saturday Night Cinema: The Sound of Monsters University Posted: 06 Jul 2013 03:00 PM PDT hat tip boingboing |

| Posted: 06 Jul 2013 12:00 PM PDT Click for full list |

| Readers push back: “Missed the rally & still fighting the tape” Posted: 06 Jul 2013 07:00 AM PDT Missing the big stocks rally: Readers push back

Last time, I talked about what investors should do if they sat out the big market rally in recent years. In brief, I advised making changes of both a behavioral and investing nature. The behavioral issues included admitting error, letting go of mistakes, changing news sources, reviewing your process and creating a new approach. The investing solutions were to develop an asset-allocation model, slowly deploy capital, dollar-cost average, rebalance, diversify and invest for the long term. The pushback from certain quarters was fierce. (Although a lot of readers sent nice e-mails or posted lovely comments about the piece, and I thank you for those.) Some folks seemed to misread what I had written. Others misunderstood the approach. So let's try this again. Before we wade back into it, let me explain what that column was not: It was not a claim that stocks were cheap; nor was it a suggestion that you must buy stocks now! Indeed, I tried to emphasize that this was not about the next few weeks or even months, but about a timeline measured in decades. The goal was to engage in a sober discussion as to what readers should be considering if they happened to have missed a once-in-a-generation rally. Toward that end, let's look at some of the pushback: ●The only way you did not miss the 150 percent move is if you bought at the bottom and sold at the high and invested 100 percent in the stock market. This is incorrect. To see why, you need to understand three things: First, you must recognize that you are not a hedge fund, and your goal as an individual investor is not to outperform the benchmark (not that most hedge funds do, but that's another column entirely). Rather, your goal is to meet some future need, be it buying a house, paying for college or retirement. Second, if you were in an asset-allocation model, you would have already owned equities and bonds. And third, you would have been incrementally selling equities into the market peak and rotating into fixed-income investments. And you would have been buying equities into the 2009 lows and selling bonds then. That is what rebalancing does. ●The Fed is printing money, and the Dow is heading to 5000! Thank you for your forecast! Truth time: How long have you been peddling that Dow 5000 prediction? How many times have you made investments based on that (or other) forecasts? What is your track record? How on earth do you think you know where the market is going to land? Sorry to have to tell you this, but you just made my point. You missed the Big Kahuna rally by investing based on your own forecasts. This is a terrible approach. ●Count on the fact that you are an outsider and not privy to the insiders' knowledge or strategy. Who are the insiders? Billionaire hedge fund manager John Paulson? His funds have gotten mangled over the past few years. Even what is arguably the largest, most successful hedge fund, Ray Dalio's Bridgewater, is down this year despite a strong market rally. The so-called insiders have done no better, and in many cases far worse, than you. ●What makes you think you know where the markets are going? Gee, I thought I made it pretty clear that I have no idea where the markets are going. But investors do not need to know that to invest intelligently. We do understand long-term returns of asset classes and valuation measures, as well as how mean-reversion works. That's most of the information you need to make an intelligent asset-allocation decision. No market forecasts required! ●I went to all cash on [the day before any recent market sell-off]. The question isn't whether you got it right on one day. Anyone can randomly do that. The issue for most investors is how much upside they miss waiting to avoid that down day (off 2.5 percent or worse). And then the follow-up question is simply this: Do you have the tools and the discipline to get back in? In recent years, I have spoken with countless people who managed to avoid the 2008-09 crash but could not bring themselves to reverse direction and jump back in after March 2009. It is an incredibly difficult thing to do and requires enormous skill and discipline. That's before we discuss the costs and taxes you pay, assuming you can consistently jump in and out of the market with near-perfect timing. (And the odds are very much against you there.) ●What should investors do if they missed the move in gold from $250 an ounce to nearly $1,900 an ounce? Good question. As mentioned, if you own a commodity index within your asset allocation mix, you will not have missed that move. But there are other factors about gold worth noting. It produces no income, dividend or yield, so valuing it is incredibly difficult. (Gold is off 35 percent since those 2011 highs you mentioned.) Second, tradable gold is a tiny asset class. GLD, the Gold ETF, is less than a $40 billion asset. Add in the gold miners (GDX) and you get an additional $7.4 billion; factor in the junior miners (GDXJ), and you get another $2 billion. All told, it's less than $100 billion (not counting gold futures). Gold bullion, on the other hand, has a total value of over $4 trillion. ●Aren't you advocating a buy-and-hold approach? I thought you were not a fan of that. No change of heart — the column was about overcoming the risk aversion that led you to miss a huge rally. I wanted to keep it simple and focus on how emotions can blind logic. Beyond the basic simplicity of the asset allocation approach we took was a more complex entrance-and-exit strategy. There are many variations, all of which attempt to generate better returns by missing some of the downside or getting more aggressive during up moves. But I'll leave that for another day. The key to investment success is simple: Have a plan. Follow it faithfully. Max out your tax-deferred accounts. Dollar-cost average. Rebalance. Diversify. And invest for the long term. ~~~ Ritholtz is CEO of FusionIQ, a quantitative research firm. He is the author of "Bailout Nation" and runs a finance blog, the Big Picture. Follow him on Twitter @Ritholtz. |

| Posted: 06 Jul 2013 04:30 AM PDT Its another glorious day in the NorthEast, as the weather has turned out to be much better than forecast (heh heh). If you live in the part of the world that isn’t 78 and sunny, well, here are my favorite long forms journalism from the week to feed your brain:

Whats up for the rest of your weekend?

Heat Rises: Dow, S&P Up 1.5% on the Week |

| Ferrari 250 GT Zagato Sanction II Posted: 06 Jul 2013 03:00 AM PDT |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment