The Big Picture |

- 10 Tuesday PM Reads

- The Fed again brings out its crystal ball

- Euro Zone Bank Stress Test

- Mitt Romney’s State of the Union Challenge on the Mortgage Crisis

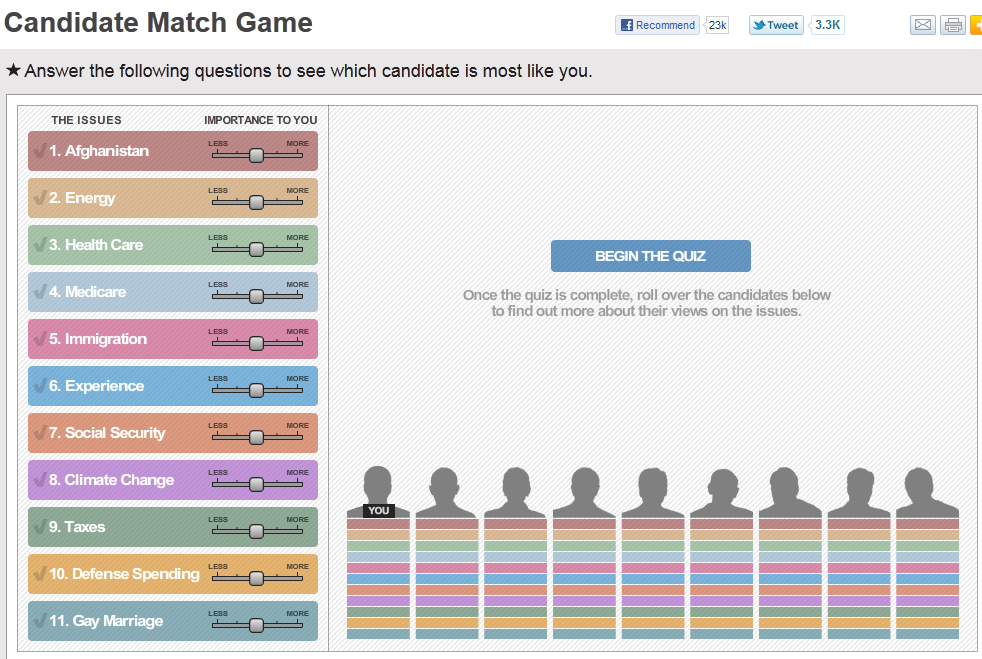

- Candidate Issue Selection Quiz

- Comparing Income, Corporate, Capital Gains Tax Rates: 1916-2011

- David Stockman on Mitt, Newt and Crony Capitalism

- 10 Tuesday AM Reads

- New Reality Show: Real Economists of the Ivory Tower

- Europe/India

| Posted: 24 Jan 2012 01:30 PM PST My afternoon train reading:

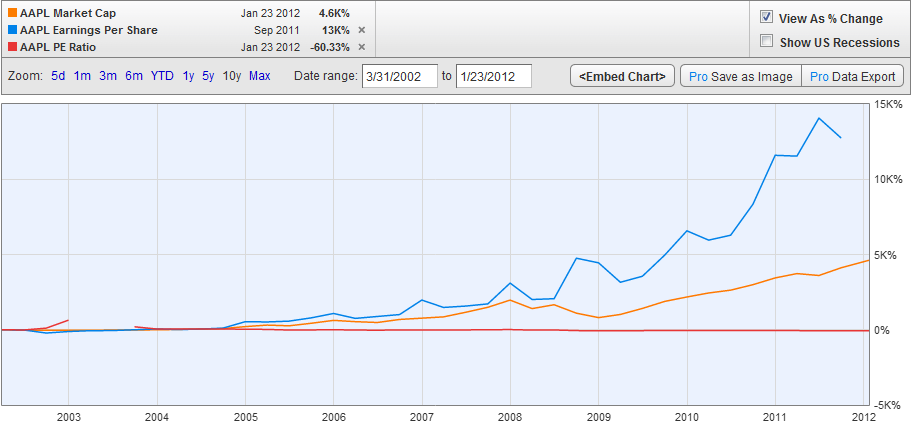

What are you reading? > How Cheap is Apple? Source Ivan Hoff Capital |

| The Fed again brings out its crystal ball Posted: 24 Jan 2012 11:44 AM PST The FOMC tomorrow will tell us at what level they want to price fix the short term cost of money and for how long. This forecast from each individual member will be based on their economic forecasts. While these forecasts will be useful from a market perspective as the Fed’s words alone can influence rates, relying on Fed forecasts as something close to ultimately being accurate has historically proven to be dangerous. For a quick instant replay check over the past 10 years, the Fed believed the US economy was on the cusp of deflation in ’02 thru ’04 and it’s why they lowered the fed funds rate to 1% and kept them there for a full year. This forecast of deflation of course was wrong as one of the great commodity bull markets of all time began in early 1999. We also know this cheap money below the rate of inflation enabled the credit bubble. The other Fed forecast of major consequence was said by Ben Bernanke to Congress on March 28th 2007, “At this juncture…the impact on the broader economy and financial markets of the problems in the subprime markets seems likely to be contained.” My point is that the extra transparency the Fed will give us today is irrelevant if they get the underlying policy wrong and the chances are they will. It is why the marketplace and the countless number of participants should be setting the cost of money, not trained economists doing so based on their econometric models. |

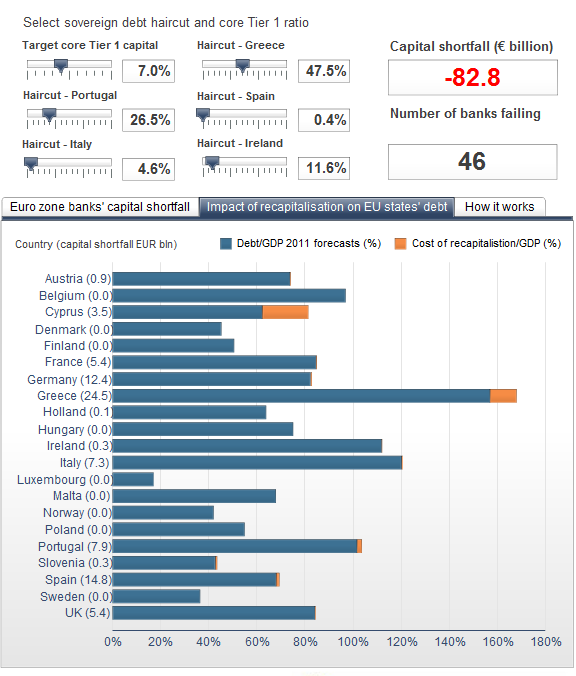

| Posted: 24 Jan 2012 11:30 AM PST Here’s another fun quiz, this one from Reuters Breakingviews: Wanna know how much Capital that needs to be raised by Eurozone banks? How much of a haircut Greek bondholders are going to take? Play with the sliders on this to find out: > Click for interactive chart:

|

| Mitt Romney’s State of the Union Challenge on the Mortgage Crisis Posted: 24 Jan 2012 10:43 AM PST Mitt Romney’s State of the Union Challenge on the Mortgage Crisis ~~~ Finally, a presidential candidate came out and honestly addressed the biggest problem in our economy, the enormous debt overhang in our mortgage market. A few days ago, Mitt Romney was at a forum in Florida talking about foreclosures, and his comments were actually refreshingly honest about our housing and banking situation and the need for a debt write-down.

Mitt Romney was pointing out that the banks are carrying debt on their books at inflated values. When was the last serious politician to make that point, openly? There’s more.

Romney is now saying that if you can’t pay your debts and your lending institution won’t work with you, walk away. Perhaps this isn’t so surprising, though, as Romney is an expert in debt restructuring. This is actually just common business sense. And finally, he offered a real solution to the mortgage debt crisis.

This is the right approach to the problem. If you force the banks to recognize losses on the mortgage debt they are holding, then all of a sudden they will have an incentive to write down debt. Otherwise, a bank will do anything it can to maintain the fiction that the debt is worth 100 cents on the dollar, including lie, harass, and robo-sign. There are ample reasons for cynicism, the cup overfloweth with them, perhaps. Still, what’s shocking about these comments is how casual they are, as if it’s common knowledge that the banking system is still insolvent and that our debt loan cannot be paid back. Among financial elites, it in fact is common knowledge. Tim Geithner noted this when he talked about Lehman Brothers and the “air in marks” on the debt it was holding on its books. And Martin Feldstein on the Republican side and Alan Blinder on the Democratic side are both arguing for debt write-downs. Everyone knows this has to happen, that the accounting manipulation needs to stop. But Mitt Romney actually said it. We’re pretty sure that Romney will walk these comments back if necessary, since he holds positions only insofar as they are convenient. Since at that same forum he called out for praise one of the most bank-friendly state officials in the country, Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi, we can probably measure his adherence to this common-sense approach in micro-seconds. But what this episode shows is that the solutions to our crisis are understood. In the book Greedy Bastards, the question of restructuring debt is considered in detail. We need a debt deal, as Romney inadvertently noted. More fundamentally, getting rid of the accounting gamesmanship will lead to a healthier economy because it will align financial assets with real economic assets. As another example, credit default swaps are linking American banks excessively to an unstable Eurozone. Credit default swaps are in fact yet another accounting game designed to further balance sheet fictions. Dick Grasso offered his solution to this obvious problem. We can, according to Grasso, simply declare these contracts online gaming, and void them. What Americans should be taking from this episode is that finance, while complex, is not conceptually hard. If it’s a lie on the balance sheet, it’s going to be destructive to ordinary people. If you stop the balance sheet lying, the economy will do better. But while Mitt Romney might have said this out loud, they all know it behind closed doors. Our question is, who will be the first to make this a policy reality? |

| Candidate Issue Selection Quiz Posted: 24 Jan 2012 09:30 AM PST According to USA Today, my choices for President are 1) John Huntsman; 2) Barack Obama; and (WTF?!) 3) Rick Santorum. > |

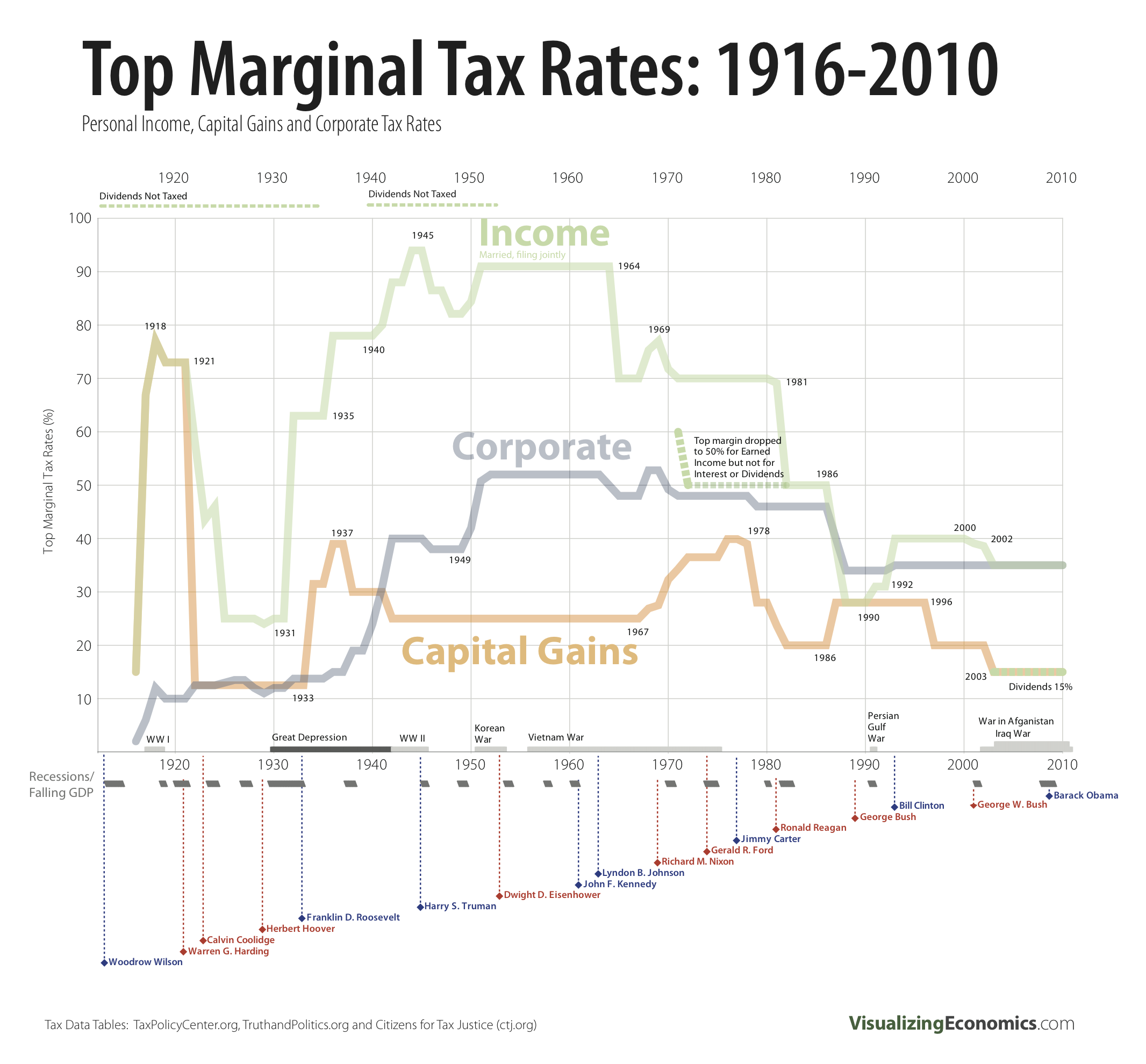

| Comparing Income, Corporate, Capital Gains Tax Rates: 1916-2011 Posted: 24 Jan 2012 08:30 AM PST Catherine Mulbrandon updated her 2010 graph on top marginal tax rates. > (Top Marginal Tax Rates graph is also available for sale as a tabloid size 11″x17″ poster). > Source: |

| David Stockman on Mitt, Newt and Crony Capitalism Posted: 24 Jan 2012 07:09 AM PST

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy January 23, 2012 Transcript after the jump

Former Ronald Reagan OMB director David Stockman joined us on The Dylan Ratigan Show today to explain explicitly why both Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich are incredible offenders and beneficiaries of corporate communism or, as he likes to call it, "crony capitalism." He specifically laid out the atrocious track record that is displayed by Mitt Romney and Bain Capital's ability to make hundreds of millions of dollars on leveraged buyouts (just to name one illustrative example: buying and selling the Yellow Pages from the Italian government.) The most important thing about the Stockman indictment of Romney and Gingrich is that it also speaks to the Obama administration's similar characteristics, through the lens of Geithner and Summers. He points specifically to the failure to reform our banking system, and the massive expansion in too big to fail financial institutions since the financial crisis as the single greatest risk to the Western economy, as well as the greatest cause of distorted incomes, poverty, and unemployment. Stockman proves that it's not about the identity of the politicians, it's about understanding the distinction between aligned interests between investors, entrepreneurs and inventors working together to solve problems — this in contrast with the misaligned interests, crony capitalists and corporate communists who use use access to power to extract money for themselves at the expense of our nation and the world as a whole. Here's the segment, and the full transcript is below: Dylan: Well, just about four hours now until tonight's debate and the economy may well actually make it to center stage here. It's certainly a favorite talking point for both of the big GOP hopefuls right now, not to mention the President himself. New data out today shows that 83% of Americans now say they are dissatisfied with the current economy—looked to poverty, looked at wealth and equality, looked to unemployment. We figure if the 1% has all the money, the other 16% must just be confused in that number. How could anyone be satisfied when, according to Gallup, more than 26% of us are unemployed or underemployed? Just the latest example of the split in the country between those that have and those that do not have and, more importantly, those that are working together in alignment to help each other and those that are screwing each other over, you know what I'm saying? I want to bring in former OMB Director under President Reagan, David Stockman, a man who is one of the most aggressive advocates of capitalism and one of the aggressive opponents of crony capitalism. I just want to continue the conversation we were having, David… David: Sure. Dylan: …about the education Newt and Mitt are giving us as they try to attack each other—your assessment of their indictments of one another. David: Well, you know, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae were a cesspool of crony capitalism; we could go on about that. So Newt was hypocritical in taking money from Freddie Mac and pretending they needed a historian. Why does a cesspool of crony capitalism need a historian? Okay? Dylan: Yes. David: But when you look over on the other side, I think, unfortunately, Romney was disingenuous when he said that he got a graduate education in company creation, job creation, and growing economy as an LBO artist. Let me tell you why. Dylan: Because people that invest money, we were just out in Silicon Valley, lots of folks there invest money all the time, they start businesses, what's the difference between what Mitt Romney was doing and what – David: Because leverage buyouts are just financial speculation. I was in the business for the same period he was and I would not pretend that I learned anything during that time that tells me how to improve the U.S. economy or how to even build companies or create jobs. What I learned was how to strip-mine the cash out of a country, a company to pay the debt. What I learned was how to powder up the pig in order to sell it in the quickest IPO or the best buyer you could do. Dylan: Did you make good money? David: Made some very large gains in some cases and had some bankruptcies in others. So the point, though, is leverage buyouts are not about growing an economy. And when you look at the record of Bain Capital, that's what it shows. Now, everybody's aware of the five companies that went bankrupt, they put in $100 million, they took out $500 million within a year or two, these five companies including Georgetown Steel went bankrupt. Okay, that happens. And frankly, if you're in that business and you want to be a speculator, fine. If you want to own a casino, fine. If you want to own a brothel, fine. I believe in a free economy. But you shouldn't pretend that somehow this gives you superior qualifications to figure out how to run the economy. Now, let's look at the other two companies on the other side to give some idea what leverage buyouts really do. They have… Dylan: Well, slow it down, though, because this is an important lesson. Walk us through it, if you don't mind. David: Well, they had – Bain Capital had two other companies where they invested $100 million and they also… Dylan: $100 million of their own money. David: Of the fund, of the fund – Dylan: So they're managing other people's money. David: Right, right. And they put in $100 million and they took out $500 million. And in these two companies, they were spectacular successes. One was called Experian; they bought it for $1 billion in September 1996. Two months later, they sold it for $1.7 billion. They bought it cheap from TRW, a big conglomerate. I don't think there was an auction. Two months later before they even moved into the house or painted the kitchen or even crossed the front door, they sold it to a British company that was run by Margaret Thatcher's former Staff Director. So I would… Dylan: How's that for crony. I mean, come on. David: So look, they made $200 million in two months, so good for them. That's great speculation. I'd call that an inside job. Now, the other one was that they bought the Yellow Pages in 1997 from the utility in Italy. They put… Dylan: And the Yellow Pages was a 22-bagger. David: Yeah, how can you make a 22-bagger in the Yellow Pages unless you bought it really cheap, you were part of a crony capitalist crowd that took it over on the cheap, which was the case. They were involved with Berlusconi and all the rest of them. Let's call that the "Italian Job." Dylan: Okay. David: So when you look at the record, $100 in and — $200 in a billion out.One was an Italian Job, one was an inside job, and five were a screw job. And that's how you make a billion dollars. Dylan: And that's a way to make money but that is a fraudulent way to represent the narrative of American just capitalism. Tim: So the question is, is there anything – can Romney, can any of these candidates draw a distinction between sort of crony capitalism and capitalism because I think the left is all about blurring those two together. Because Obama will do the crony capitalism while attacking capitalism at the same time. It seems like Gingrich certainly can't make that distinction given his record, but is there – can Romney do it to… Dylan: Or do we, the Press, have to do it? I mean, that's really what we're trying to… David: I think the Press can do it and I think Ron Paul's doing it. Now, whether you like what he has to say or not, he's been consistent over the years and over the years. Let the free market work. Now, if we would only get back to letting the free market work—and, frankly, Obama's been just as bad—they didn't do anything about a banking system that's more out of control today than it was when they came in. They put into the key economic jobs Summers and Geithner and all of the rest of them, Bernanke, who had caused the problem in the first place. Dylan: So how do we solve this? One at a time, one at a time. Sam: How did these people cause the problem in the first place? It was buy regulation. I mean, so this is… Dylan: Let him answer, let him answer. David: It was not deregulation. It was mainly free money from the Fed, almost zero interest rates, massive encouragement for people to leverage, speculate, and then… Dylan: And the swaps market. David: …well, but the reason those worked is you had the Greenspan put and the Bernanke put which told speculators borrow 99 cents, buy 100 cents worth of speculative assets, and don't worry that anything bad is going to happen because the Fed has your back. That's what caused this. Imogen: What you're saying is he's done absolutely nothing since 2008. David: We have done nothing. Imogen: Is it – okay, so is it going to take worldwide financial meltdown thanks to the Euro zone, say… David: Absolutely. Imogen: …for a reset meeting because it sounds to me that – surely, we're going to hit rock bottom somewhere. David: No, we're doing the same thing over and over. The top six banks in 2008 had $6 trillion of assets in the United States; they now have $9 trillion. The top three banks in France have $6 trillion of assets and the GDP is only $2.5 trillion. We have got banks everywhere in the world that are out of control, stuffed with bad asses being propped up by the central banks, the ECB and the Feb, and they're playing this game of kick the can and pretend that everything's rosy. Dylan: So put yourself in the American people's position. So now – because you and I are obviously in full agreement on the – it's the basic theme of Greedy Bastards as a book, it's the theme of this TV show, which is that there's this system with both political parties facilitating a totally distorted capital market with banking, trade, and taxes. If you look here in reality at a President who has facilitated a complete cover up of all that with his apparatus and two potential aspirants, one who's on the take in the classic crony capitalism sense of Fannie and Freddie (I'm your historian), and another one who really is doing the closest masquerade of a capitalist by buying businesses and hiring people and firing people, but the unwritten component is that his motivation is not to create value or the business's motivation is not to create value, it's to extract money using other people's money. As we are all learning this, it becomes remarkably frustrating for the American voter, let alone the people sitting around here and anywhere else, to reconcile it. So I'm interested on your thoughts of how we can apply pressure to all three of these people—the President, Mitt Romney, and Newt Gingrich to talk about the elephant in the room. David: Well, the elephant in the room is really the Federal Reserve. The problem behind all this is the tri-fecta of almost free money. When debt has an interest rate on it of zero overnight or for the short term or 2% for ten years, you're encouraging people to build up leverage and speculate. It doesn't help Main Street, it only showers gains [cross-talking 09:04]. It makes the finance sector bigger and that doesn't help the economy. It's just churning. Sam: You saying that capital constraints – you're saying that any type of regulations about speculation, those would be irrelevant. David: No. Sam: The only issue here is cheap money. Is that what you're saying? David: One issue is cheap money and the second thing is the banks. The banks are not free enterprise institutions. They're wards of the state, they need to be strictly regulated, we need to bring back Glass-Steagall, and we need to get banks out of trading. Banks should be in the business of taking deposits and lending. Dylan: Right. David: If you want to be Goldman Sachs, give up your bank charter… Dylan: Right, and be a man. Be a man. David: And be – if you want to speculate, be a hedge fund, which is what they are, then do that, but don't have the Fed window, don't have deposit insurance, which their bank has… Dylan: And then walk around like you're a tough guy, Mr. Capitalist, while you're taking out of the back. Anyway, thank you very much. Come back sooner rather than later. You're also set the table perfectly for Governor Spitzer's visit tomorrow. There's scorched earth here today. Nice to see you, Sam. Nice to see you, Tim. Nice to see you, Imogen. I look forward to seeing tonight's debate to hear these two throw housing and unemployment at one another. Interesting times. |

| Posted: 24 Jan 2012 06:30 AM PST My morning reads:

WhatTF are you reading? > ECB May Hold Key to Exiting From Greece’s Debt Labyrinth |

| New Reality Show: Real Economists of the Ivory Tower Posted: 24 Jan 2012 05:30 AM PST Dan Alpert is a founding Managing Partner of Westwood Capital. He has more than 30 years of international merchant banking and investment banking experience, including a wide variety of work-out and bankruptcy related restructuring experience. Dan's experience in providing financial advisory services and structured finance execution has extended Westwood's reach beyond the U.S. domestic corporate finance market to East Asia, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. In addition to his structured finance expertise, Dan has extensive experience advising on mergers, acquisitions and private equity financings. He has additional expertise in evaluating and maximizing the recoveries from failed financing vehicles affiliated with a common borrower/issuer. >

Over recent months, an intense debate between two opposing schools of economics has reached a crescendo. The relationships—at least in print—among members of the so-called saltwater school of economists (those leaning towards Keynesian fiscalism, and more-managed forms of capitalism) and economists in the freshwater or Chicago school (broadly favoring less-regulated, free-market economies with an emphasis on monetary matters) has never been overly warm. But the degree of name calling and apparent unwillingness to find common ground has come to a head since the beginning of the year—especially following the U.S. economic profession’s annual conference the first weekend after the New Year’s break. With the World Economic Forum at Davos on tap for this week, providing yet another occasion to read tea leaves and tout theories, it is a good time to consider whether polarization of opinion isn't as much of a problem as polarization of income and wealth in the developed world. Is the almost complete absence of consensus among mainstream economists yielding drama but paralyzing decision? To my view, the answer to the foregoing is a decisive yes. So, I have decided to tackle the issue with a bit of humor, together with my own explanation of the underlying problems and suggestions for how to go about reaching a very elusive meeting of great minds. The debate as it proceeds each week in what I now title Real Economists of the Ivory Tower provides an often amusing diversion for its wonkish audience—but I am afraid it will never be successful mass entertainment. Its cast—Paul, John, Robert, Brad, Simon, Scott, Tyler, and others—can fling their credentials and arguments at one another, but if you don't know who I am referring to in this sentence, I doubt you would DVR the series. (Fortunately, we all have a guy named Mark—who happens to be a new colleague of mine in our work at The Century Foundation—to keep everyone honest, so you can always head over to his invaluable blog if you miss any episodes.) Economist cat fights, alas, seem never to involve sex. There's money, but no bling. And the typical insults run the gamut from “you weren’t listening during Econ 101″ to “you are so out of it that you can’t even understand what I am saying.” That economists don’t understand what each other are saying, of course, comes as no surprise to laymen—as everyone else can't understand them either. So, with that in mind, and as technical as the subject matter may be (this is, actually, a serious essay), I’ll do my best to present in plain language the problem that is the source of the foregoing drama. For more advanced readers, I will provide a somewhat unconventional explanation of a possible middle ground that I will call, for now, an Exogenous Supply Incongruity (so named as to make certain no one understands me either until they read on). The Synopsis to Date In the major nations of the developed world—first in Japan, over a period of nearly two decades, then in the United States, beginning in 2008, and now (however reluctantly) in Europe—monetary authorities (central banks) have been massively increasing the portion of the money supply over which they have direct influence in an effort to revive their economies. In a conventional cyclical downturn, it is received knowledge that looser money encourages additional economic activity (spending, investment, employment, etc.) by making money cheaper and discouraging saving/hoarding. Cheap and ample money would also encourage lending, and thereby would be expected to increase broad money supply—and, ultimately, to induce inflation across economic sectors. In response to economic collapse, central banks have now gone well beyond conventional methods of expanding money supply, including purchasing investment assets (typically government issued or insured) in the open markets and pushing cash out to the sellers of those instruments, in the expectation that they will do something with that that cash to improve economic activity. This action is known as quantitative easing, which is a fancy term for what desperate central banks must resort to when they've already dropped short-term interest rates to essentially zero (the so-called zero lower bound, beyond which conventional monetary policy is obviously useless). A limited amount of re-inflation itself is generally regarded as being a net positive to the recovery of an economy, especially after a debt binge such as we experienced in the 2000's. The principle concern in this regard, however, is not to induce runaway inflation—something that is bad for a whole host of reasons that I do not need to go into here (especially because a majority of Euro-American economists and politicians appear to be preternaturally so afraid of inflation that one must assume that they all must know exactly why that is—or perhaps not, but I digress). In any given developed nation, along with inflation, one would expect to see the value of that nation's currency fall in relation to those of others that are not experiencing similar rates of inflation—thus furthering inflation in imported goods and making the inflating economy more competitive relative to those other countries. One would also then expect interest rates to rise in order to maintain levels of real (inflation adjusted) returns, thus getting things off the zero bound and back to normal. The problem today is that, not only have conventional and extreme/unprecedented forms of monetary easing failed to restart brisk growth in developed economies, but massive monetary growth has not resulted in sustainable inflation, either. To be sure, there have been spikes in U.S., U.K., and European inflation (and slowing deflation in Japan—which is how you need to measure things over there), but they have arisen from expectations that quantitative easing would surely result in sustained inflation—not the actual thing itself.

All of this has, understandably, sent the freshwater crowd into a defensive tizzy of the sort you might hear from the religious right in response to taunts like "God is dead." (Of course, the gods of the Chicago school are dead, which is unfortunate, because I'd love to hear Friedman and Hayak chime in on all of this.) Trying hard to make the facts on the ground fit into theories and models that freshwater economists have spent their careers studying and advancing is a tough business under the current circumstances. Not only are they up against the dreaded zero bound, and the arguments from the other side regarding the existence of a "liquidity trap" (in which excess liquidity tends to exacerbate matters), but the failure of the economy in the first place can be arguably laid at the doorstep of the freshwater crowd, following a quarter-century of road-testing various forms of the supply side-oriented consumerism they directly or indirectly advocate. The dramatic foil for the supply-siders is provided by demand-oriented Keynesian economists, and so-called New Keynesians, who for that same twenty-five-year period have been forced to endure the slings and arrows hurled at them from colleagues whom they still regard as contrarian newcomers. Full disclosure: while I am one-quarter of Austrian lineage (a joke about . . . well, too complicated, let's just say I think there is some degree of moral hazard in "free money"), the other three-quarters of my economic orientation is very much Keynesian. But I am doing my best to be evenhanded here, even critical with respect to those with whom I otherwise agree. The dramatic conflict in our new reality show: it is hard to ignore that aggregate U.S. and global demand is inadequate to foster a robust recovery. Even the supply side/monetarists agree. The issue is how to address that imbalance (and its related imbalances). Thus far, and I am deliberately over-simplifying, the fiscalist Keynesian response has been a lot of "I told you so" combined with calls for governments to spend more money on direct employment to drive demand (I have made similar calls—without, I hope, any vindictive rejoinders). It is also suggested that governments borrow as necessary to finance that spending, on the theory that long-term interest rates have never been lower, excess labor has not been more abundant since the Great Depression, and there is a pretty good history of government spending serving to re-prime private sector economic activity. The position of the saltwater school is thoughtful, pragmatic, and often quite insightful with regard to the flaws in the arguments of the Chicagoans. But the debate has stalled, partly because instead of persuading and finding common ground, the obvious (at least to me) victor is seeking its intellectual spoils. I am a businessman first and a writer on macroeconomics second, and while this stuff may be par for the course in academia, we are not getting the deal done. We are not finding the consensus necessary for those with less knowledge (our political leaders) to be able to trust that there is one, and adopt it. "Call Rewrite!" So, as much as the drama of Real Economists of the Ivory Tower can be entertaining in a sophomoric sense (and it is terribly funny), I'd like to take a shot at coming up with a new treatment that might result in the show getting better ratings. It involves the "coastal" economics crowd doing the following:

Finally, there's that matter of why the monetary "inflationistas" are not seeing things clearly. Yes, there is that little wonky thing about assuming the velocity of money is a constant—which anyone on the coasts knows is untrue, because we can sit at the ocean and watch the waves to contemplate how amplitude, frequency, and velocity are all variables (sorry—really wonked-out joke). But bit of humor helps the medicine go down my friends! And that leads us to, Episode 1: Warren Buffett Walks into a Bar. . . . . . . And he's forgotten his wallet but really craves a beer. So he sidles up next to me at the bar and takes a cocktail napkin and writes an IOU on it for $5 (its Omaha, prices are lower than here in Manhattan) so I will buy him the beer. While it is Warren Buffett, and I therefore might want to just frame the napkin as a collectible, let's assume that I take his IOU because he is, well, loaded, and for the purposes of this argument has nearly infinite credit. The cocktail napkin is basically what is known as fiat currency (assuming it's not a forgery). Warren just created money out of what I would otherwise have used to wipe the salt from the bar nuts off my fingers. After all, he got his $5 worth of beer, he still has his $5, I gave the barkeep my $5 and I have the napkin. There is now $5 more in the world, made out of what otherwise would have been crumpled up tissue (less the $0.01 value of the napkin itself if you want to get all technical). Now, you're saying "no, the IOU is a loan, it is credit, not money." But for the purposes of our story, we are regarding Warren as a de facto money printing press, not only because he has so much money and makes so much more of it every day that he might as well be one, but because of the fact that, like any issuer of fiat currency, the ability to get it accepted as a means of exchange (much less as a reserve for storage of wealth) is dependent on the magnitude of the economy backing the entity that is doing the issuing. You probably see where I am going—but if you don't, then pull out of your pocket the crumpled U.S. dollar bill you've got jammed in there and have a read up top where it says "Federal Reserve Note." Our money is—of course—a note from the Fed promising to pay you with, well, another note just like it. Oh, I forgot to tell you—Warren didn't offer me interest on his cocktail napkin IOU, and neither does the Fed's currency. Greatest deal on earth—the Fed can "drink all the beer" it wants and pass around pieces of paper with no interest that are only redeemable for other pieces of paper. Moreover, when it creates dollars and uses them to buy notes that actually pay interest (like U.S. Treasury Bonds), it can—in theory—make infinite profits. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve actually does have an "owner" that has given it a small amount of actual capital (not that it needs it—since it prints the currency and can always print more). That owner is the U.S. government, the Treasury of which takes the Fed's profits (called "seigniorage," although the word used to mean something else entirely, but is held onto in order to make economists less understandable) and guarantees the solvency of the Fed. Back to Warren. He is a very generous person and keeps writing cocktail napkin IOUs to buy everyone in the bar round after round. You might think that Buffett's Beer Binge would have resulted in the barkeep's ability to raise prices. After all, the bartender can also take those IOUs from people who were handed them by Warren—so the bar quickly fills with a lot of "money." But let's assume that jobs are scarce and some patrons merely hold on to the napkins and leave the bar. If the barkeep tries to raise the price of his goods, he finds that there are a lot of other bars in the neighborhood craving customers, and that there simply aren't enough patrons to go around and support all the bars adequately—despite the plentiful stock of literally paper money. In fact, there are so many bars with so many empty tables that many of them run extended happy hours at deep discounts. Over time, even though our fictional Warren has gotten into the habit of buying everything with cocktail napkin IOUs, and they are used for the purchase of many goods, there are still way too many goods and way too little wage income in Omaha (this of course is a fictional Omaha—Nebraska is enjoying an energy and agricultural boomlet right now, but I've got to take my gazillionaires where I find them). So over time, in the midst of such excess supply, the price of beer and other goods actually falls. And, wouldn't you know, for that original $5 cocktail napkin, I can eventually buy two deeply discounted beers instead of one. Measured in beer, then, the value of my napkin has increased, despite the fact that Warren has gone on a tear and issued napkins like mad, and despite the fact that maybe folks might be worried about napkins' continued efficacy as a means of exchange and a reserve of wealth. But, as I said earlier, Warren is the richest guy out there, and his fortune vastly exceeds the billions of cocktail napkins he's issued—so who else's cocktail napkins are you going to want to hold or accept? The Denouement Ultimately, the foregoing storyline shows us that the dilemma is not about the creation of nearly endless (or potentially endless, in the case of the Fed) amounts of fiat currency. It is also not about the credit of the issuing entity if the fortune (or size of economy) underlying that issuer is large enough. Whether or not inflation will ensue from creating fiat money, whether that money will rise or fall in relation to other currencies, and whether the issuer's affiliated fiscal entity (treasury) will need to pay more or less to borrow is, I believe, ultimately an issue of the relative purchasing power of the currency, which—in the country of its issuance—is a function of supply and demand, both internally and globally. We are not living through "ordinary times"—the developed world is no longer an island unto itself. The imbalances and instabilities that are associated with the continuing absorption of labor in the post-socialist emerging nations, and the excess capacity and capital generated thereby, make the correlation of classical forms of economic thinking with the facts and circumstances prevailing around the globe very difficult, if not impossible. The United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe are in a slump, not only as the result of the bacchanalia of borrowing over the past decade, but also because we are met with extraordinary competition at lower prices. Accordingly, our goods/services pricing, and asset value complex, is being naturally driven downward as the outcome of relatively simple supply and demand calculus. Whatever re-employment we are slowly experiencing in the United States is occurring because wages here are becoming increasingly globally competitive. The dollar is stronger, and medium- and long-term interest rates are lower because the purchasing power of the dollar (domestically) is either growing or is not deteriorating as quickly as it was. If we wish to continue down the path of global re-competitiveness and domestic re-employment, the foregoing must continue. And it must continue in the face of more emerging population being drawn into the global free market each year, until a combination of emerging market demand and a more competitive developed world sufficiently resolves present imbalances. That is the only way we can continue to add jobs, and it involves a very long, painful, and destabilizing path. It is therefore reasonable that, if wages are low and becoming lower, borrowing is cheap, and we have plenty we could be doing to improve our economy; for example, we should consider making our infrastructure more competitive while soaking up some of the excess domestic labor with government-stimulated jobs to take full advantage of our resources. The experience of Japan, which was faced with the rise of the Asian Tiger economies after its own credit bubble burst two decades ago (and then again with the rise of the BRIC nations a decade later), is highly instructive. Japan has maintained its surplus current account and net exporter status (with a few slips along the way) by enduring now-decades of on-again, off-again deflation in wages, prices, and assets. Its globally low borrowing costs and its strong currency reflect the impact of such deflation in the form of higher real returns and greater purchasing power, respectively, to the holders of its government bonds and the Yen. And here's the punch line. One doesn't need to trash the entire freshwater body of work to accept that the facts on the ground have shifted dramatically. Supply-side and broader monetarist views do have a place in the debate. Even the so-called Laffer Curve (which is really an illustration originally made by Keynes) has some legitimacy if governments begin to tax incomes too heavily—although that is certainly not the case today. Let's go back to blaming the communist world (for having terminated itself), if that's what we need to do to get to a sufficiently directive consensus among economists. The followers of Keynes should be magnanimous in victory, not just because it's the right thing to do, but because what makes them right are the very global facts that few of them saw coming either (fair is fair). We have an entire edifice of Euro-American policy and political thought that has been keyed in to arguments (supply enhancement, shrinking government spending, and trickle-down hypotheses) for a quarter century that simply have little application today—despite the theoretical elegance thereof. And until there is some agreement among leading economists that the world has changed and we need to suspend this now-ancient debate for a period (as we would, for example, in a military conflict that threatened our nations), the economics establishment will be of little practical use to governance or to our peoples. That is the reality of this "show." |

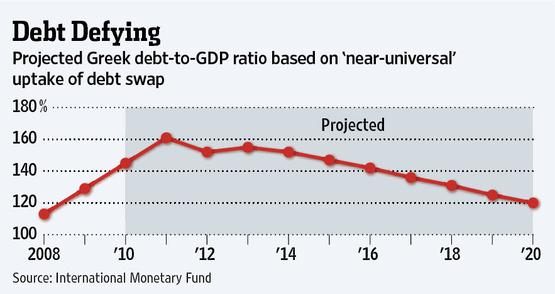

| Posted: 24 Jan 2012 05:23 AM PST European Finance Ministers want more from Greek creditors. The difference between the two parties seem to be coming down to what interest rate Greece will pay going forward and last night Finance Ministers wanted a lower coupon than creditors were willing to pay. Also, aside from the PSI discussions, officials realize that Greece’s economic reform has been “derailed” according to the Dutch FM and Juncker, the head of the FM’s said “it’s obvious the Greek program is off track.” The question of Greece getting another tranche of money to meet its March bond payment is certainly not assured. Italian bond yields are higher for the 1st day in 7 and French banks are trading down after S&P downgraded the ratings of SocGen and Credit Ag last night. Surprisingly, euro zone manufacturing and services composite index rose to 50.4 from 48.3, the best since Aug led by strength in Germany but New Orders, Backlogs and Employment all fell. In Asia, India unexpectedly cut its bank reserve requirement ratio by 50 bps to 5.5% but left interest rates unchanged and they said “the growth/inflation balance of the monetary policy stance has now shifted to growth.” The Sensex index rose 1.5% to the highest since mid Nov in response. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment