The Big Picture |

- More Signs You Are a Terrorist: Young or Use Social Media

- The Fed Still Hung Up On Wealth Effect . . .

- The Pandora Letter

- 10 Tuesday PM Reads

- How Much Do Market Peaks Lead Business Cycles?

- Spain to request a full scale bail out, finally?

- S&P 500 Index at Inflection Points, Market Returns

- Spain/RBA

- Five Questions about the Federal Reserve and Monetary Policy

- Big Picture Conference Tickets Reader Contest!

| More Signs You Are a Terrorist: Young or Use Social Media Posted: 02 Oct 2012 10:30 PM PDT U.S. Military May Consider You a Potential Terrorist If You Are Young, Use Social Media, Or Question "Mainstream Ideologies"

Wired reports today:

And the government has more or less classified journalists as terrorists. So it's time for an updated list of actions and beliefs which government officials have said may indicate "potential terrorism" … The following actions may get an American citizen living on U.S. soil labeled as a "suspected terrorist" today:

Holding the following beliefs may also be considered grounds for suspected terrorism:

|

| The Fed Still Hung Up On Wealth Effect . . . Posted: 02 Oct 2012 05:11 PM PDT |

| Posted: 02 Oct 2012 02:30 PM PDT http://bit.ly/RKfiSk He’s on the wrong side. His own. Read any financial analysis and you’ll learn investors are not bullish on Pandora, because it pays most of its income in royalties. Is this the listener’s problem? Is this the artist’s problem? Is this anything but Tim Westergren’s problem? If you want to screw others, if you want a personal advantage, you execute behind the scenes. Does Justin Bieber e-mail all his followers and say he’s scalping his own tickets? That fewer than 10% are available at the public onsale? If it’s dirty work you’re involved in, you want no sunshine on the subject. In other words, Tim Westergren doesn’t know Internet Rule #1. That on the Internet, the public comes first, people count. Be duplicitous, be less than honest, and your audience will disappear. Look at Netflix… All its reasons for changing fees had to do with the company’s bottom line, it didn’t make sense for the customer, which is why there’s been a backlash that has permanently hobbled the company. Netflix used to be cool, now it’s just another outlet that streams content. Pandora’s gonna be crushed by Apple. Hell, that’s what Apple’s done time and time again. It crushed Diamond, maker of the Rio MP3 player, it killed Nokia… Know anything about computing, and you know the big kahuna can turn your cash cow into a feature and you can go out of business. Once upon a time, spell checkers were standalone programs, that you purchased… Can you imagine paying for a third-party spell-checking program for Microsoft Word today? Hell, can you imagine needing the bloated features of Microsoft Word tomorrow? That’s Microsoft’s challenge. Preparing for tomorrow. That’s what the Surface is all about. A way out of the desktop mess. Desktops are disappearing like buggies drawn by horses. Turns out most people don’t need the horsepower and the features, of either desktops or laptops. A tablet is good enough. Turns out you pick what you want to hear from Spotify and also get a Pandora-like radio service. What’s Pandora’s end game? EXTINCTION! What Westergren has done right is get apps in cars. That’s what built Sirius XM, he’s following their blueprint. As for comparing Sirius XM with Pandora, the day Pandora gets Howard Stern on the service is the day I change my opinion. Pandora is just a bunch of stuff you don’t want to hear mixed amongst a few unknown gems that make you feel good because you discovered them. Is this the future of music discovery? Panning for gold? No, on the Internet people deliver gold right to your inbox. Pandora is inefficient. But that’s just my personal bias. Your mileage may vary. You may like Pandora, that’s fine with me. But why should you be obligated to ensure Tim Westergren and his company make more money? It’s like Bank of America e-mailing me to support deregulation of the financial sector because I’ve got an account there. How is this going to benefit me? How is it going to benefit the listener if Pandora pays fewer royalties? It’s not like my computer is gonna turn into an ATM and spit out cash. Greed. That’s what our country runs on. Everybody’s willing to step on another to get even more. It’s not only Westergren and bankers, it’s artists, it’s everybody. Class warfare? It’s what we’ve got all day long. Teachers are chumps who should be pushed down the food chain. Military men and women are lauded, just don’t make me join their ranks and while we’re at it, let’s lower their benefits. It is not my obligation to improve Pandora’s business model. It’s not my obligation to make the stock go up and line Pandora’s pocket. I’m stunned that Tim Westergren is too blind to see this. – http://www.twitter.com/lefsetz – http://www.lefsetz.com/lists/?p=subscribe&id=1 |

| Posted: 02 Oct 2012 01:00 PM PDT My afternoon train reading

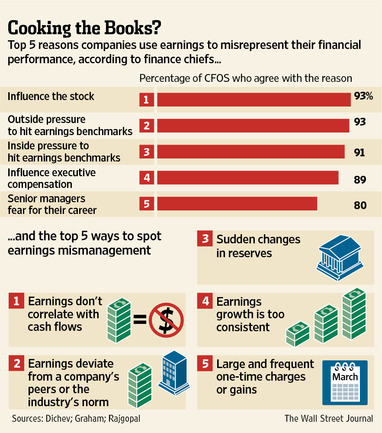

What are you reading? > Earnings Wizardry |

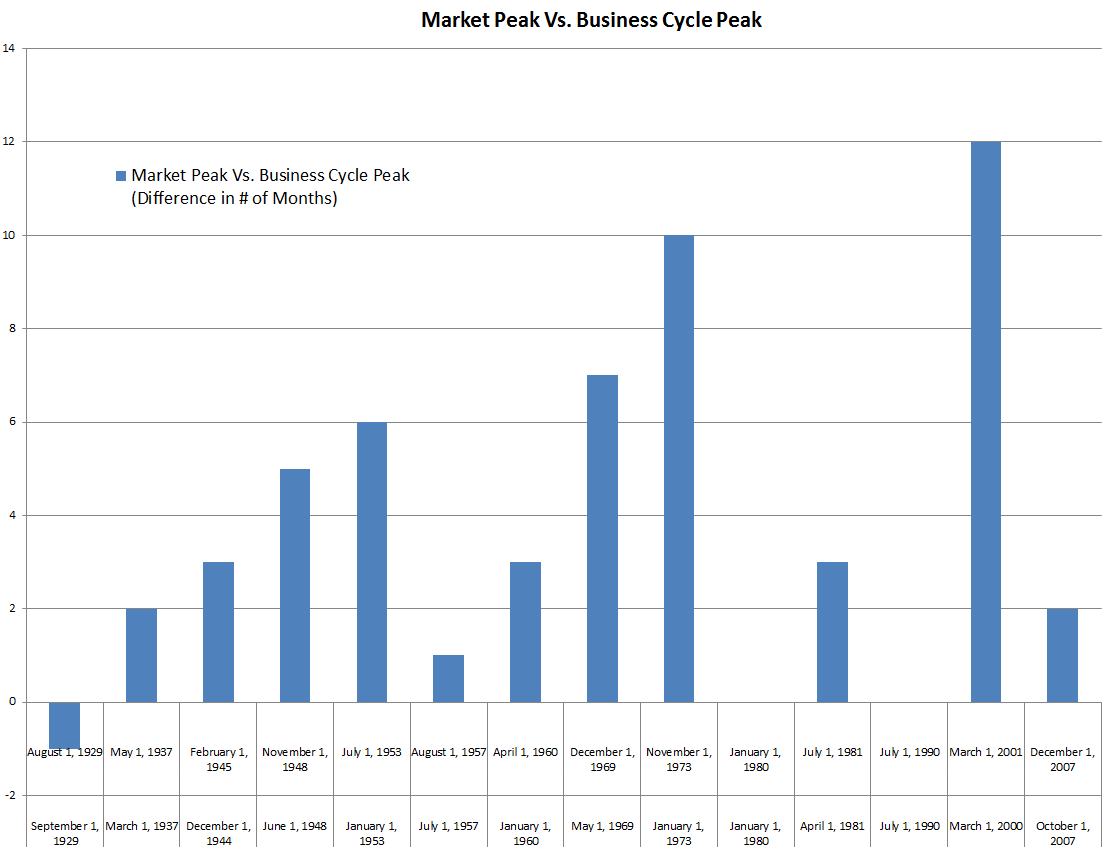

| How Much Do Market Peaks Lead Business Cycles? Posted: 02 Oct 2012 10:23 AM PDT

Its one of those things you hear your entire career: “Markets always lead economic cycles.” Indeed, I’ve heard this repeated most often by people saying “The markets lead the economy by 6 months to a year.” What does the data show? It shouldn’t be that hard to figure out what the NBER peak cycle was and to plot that against market highs. As it turns out, there have been 14 such cycles since 1929. Sometimes, the business cycle peaks before the market does. Most of the times, the market peaks out before hand — but not by as much as you might imagine. The lead has been contemporaneous a few times, or as much as The average of these 14 events is just under ~~~ UPDATE: We had a 1 year error in the spreadsheet for 2000 (breaking in new intern) — I fixed it and updated the chart (old chart is below)

|

| Spain to request a full scale bail out, finally? Posted: 02 Oct 2012 07:50 AM PDT The Australian central bank, the RBA, cut interest rates by 25bps to 3.25%, as I had expected – the lowest since 2009. The news, which was not forecast by the majority of analysts, has weakened the A$, currently US$1.0307. The RBA added that they wanted to stimulate demand outside of the mining sector and, in addition, that “The peak in resource investment is likely to occur next year and may be at a lower level than earlier expected”. Australia’s economy is materially dependent on China (roughly a quarter of its exports go to China) and with a slowing China…….Mr Stevens, the RBA governor reported that “Growth in China has also slowed, and uncertainty about near-term prospects is greater than it was some months ago”. The RBA may well cut rates further this year, quite possibly as early as next month, though most likely in December; The Japanese economy minister Mr Maehara is threatening to buy foreign bonds to weaken the Yen and to create inflation of 1.0%, the target set by the BoJ. He added that the government will be more vigilant of the BoJ’s actions. At present its just talk, but the Japanese will be forced to act soon. I keep watching the Yen, but will not short at present. However, in due course……; South Korean inflation rose to +2.0% Y/Y in September (+0.7% M/M), from +1.2% in August, higher than estimates of +1.8%, due to higher food costs as a result of typhoons, but is at the banks minimum target of +2.0%, suggesting that central bank will cut rates this month. With a country dependent on exports – which are tanking, the authorities have little choice, other than to ease. September PMI fell to 45.71, from 47.5 in August, confirming the severe downturn facing the economy; Negotiations between the Troika and Cyprus have broken down. The Cypriots, who are lead by a Communist Party, are seeking a bail out from the EZ and are threatening to leave the Euro if the terms are too tough.They are also talking to the Russians to provide aid on suitable terms – good luck. Basically, its those Greeks again; Talks continue between the Troika and the Greek authorities to resolve further austerity cuts deemed necessary. Apparently, the Troika has requested “clarification” on certain issues (some E2bn of alleged savings proposed by the Greeks) – basically diplomatic language for get real and stop the playing games. Well, no surprise – after all, it is Greece. More comments from German’s that Greece will need more aid – looks like the German’s are going to try and help. That’s going to be interesting, given the reluctance of the Dutch and the Finns to continue to bail out the country; Moody’s report that Spanish banks need E70bn to E105bn in new capital to maintain the capital ratios of its banks above the targets it set last year. The Spanish believe that E53.7bn will be sufficient, a figure reported by their advisers Oliver Wyman. Whether even E105bn will be sufficient is questionable – what’s clear however is that Spanish banks need a lot more than E53.7bn though. Messers Wyman used a core capital ratio of just 6.0% under stressed conditions, rather than the 8% to 10% used. Ireland, for example, used a 9% core capital ratio. The Spanish are unwilling to seek additional funds as they do not want their debt to GDP ratio to increase even further. However, the bottom line is that the current debt load is unsustainable and Spain will need to restructure its debts in due course, most likely; The French bank Credit Agricole’s foray into Greece has cost it E9bn. Credit Agricole is to sell its its Greek bank Emporiki for E1, yep that’s E1 – no typo. In addition, they are to inject E550mn of capital ahead of the sale and will subscribe to E150bn in convertible bonds to be issued by the purchaser, Alpha bank; It looks as if the Spanish authorities have finally come to their senses are are to request a bail out from the EZ in the near future. However, Germany has asked the Spanish to hold off, preferring to deal with all of the countries that require a bail out at one time (Greece, Cyprus and Spain), rather than one at a time, due to possible problems with the Bundestag. In addition, the Germans are conscious that they have just agreed to a E100bn bank bail out facility for Spain. Not at all sure that Spain can wait, though. Spanish unemployment rose by +1.7% M/M in September, increasing the total unemployed to 4.7mn – Spanish unemployment is around 25%. Mr Rajoy is testing sentiment in the 17 regions before deciding on how to proceed; EZ August PPI rose to +2.7% Y/Y` (+0.9% M/M), above +1.8% Y/Y in July and forecasts of +2.6% – higher commodity costs and tax increases, basically; German newspapers allege that Mr Draghi’s/ECB’s plans to buy short term peripheral debt could be illegal - a view expressed by Mr Weidmann or Mr Weirdmann, as I prefer to call him – who is seeking a legal view. I understand the arguments, but (I stress I’m no lawyer) I don’t believe that they will be upheld; The US ISM factory index unexpectedly rose to 51.5 in September, from 49.6 in August and well above the forecast of 49.7. The new orders component rose to 52.3, from 47.1 in August, a 4 month high. The employment component also increased materially to 54.7, from 51.6. However, prices paid rose to 58,.0 from 54.0. The better US numbers are in stark contrast with equivalent data in Asia and Europe and also are much better than weaker recent US economic data; Mr Bernanke reiterated that the FED would hold rates at low levels into mid 2015, though stated that he did not expect the economy to be weak up to that date. He emphasized that inflation had not risen and that expectations of future inflation levels “remain quite stable”. He reminded politicians that they had responsibility for fiscal issues ie deal with the fiscal cliff problem, boys and girls. Mr Paul Volcker confirmed that he did not see inflationary problems, as yet; Bloomberg reports that the lack of interest in buying derivatives to protect against possible inflation has not materialised, suggesting that a material rise in US inflation is not expected over the next 6 months at the very least. I very much believe that alarmist comments of rising inflation in the US, following the easier policies by the FED, is unwarranted. Longer term bond yields have also declined, not what you would expect if investors fear impending inflation; US construction spending declined by -0.6% in August, the 2nd consecutive monthly decline. August’s data was revised higher though. The decline was due to lower non residential spending; J P Morgan has been sued for allegedly defrauding investors who have allegedly lost more than US$20bn on MBS’s issued by Bear Sterns. The New York attorney-general stated that Bear Sterns “had committed multiple fraudulent and deceptive acts in promoting and selling” MBS’s. Together with J P Morgan, Goldman’s and Wells Fargo have also received notices from the SEC, warning them that they may face civil charges for alleged failure to provide information to investors on the quality of the loans, including delinquency rates and defaults; Outlook A number of Asian markets were closed today. The rest closed flat to marginally higher. European markets are trading somewhat higher. US futures suggest a higher opening. November Brent is trading around US$112.31, with gold at US$1781. The Euro is up above US$1.29 today – cant understand why. I remain short. The A$, though is weakening – I remain short. EZ peripheral bond yields are lower on expectations that Spain will seek a bail out shortly, which will enable the ECB to buy short term Spanish debt. Whilst central bank policy action is supportive, markets are likely to drift and don’t look terribly exciting, ex, as usual, geo political risks. Yes, the US earnings season is just around the corner, but markets are really moving on Central Bank and government policy action, rather on fundamentals. Closed my mining shorts, though retain my European (mainly UK) financials. Cant see China doing anything ahead of the confirmation of the leadership at the Congress commencing on 8th November. However, the Chinese will want stability ahead of the Congress and have the tools/firepower to play their markets – they have control of significant funds, which they could use. Subsequently, I continue to believe that the Chinese authorities will have to embark on some kind of stimulus programme – their economy is declining, I believe, far faster than most think. However, I remain increasingly bearish on China, in particular, in the medium to longer term. Kiron Sarkar 2nd October 2012 |

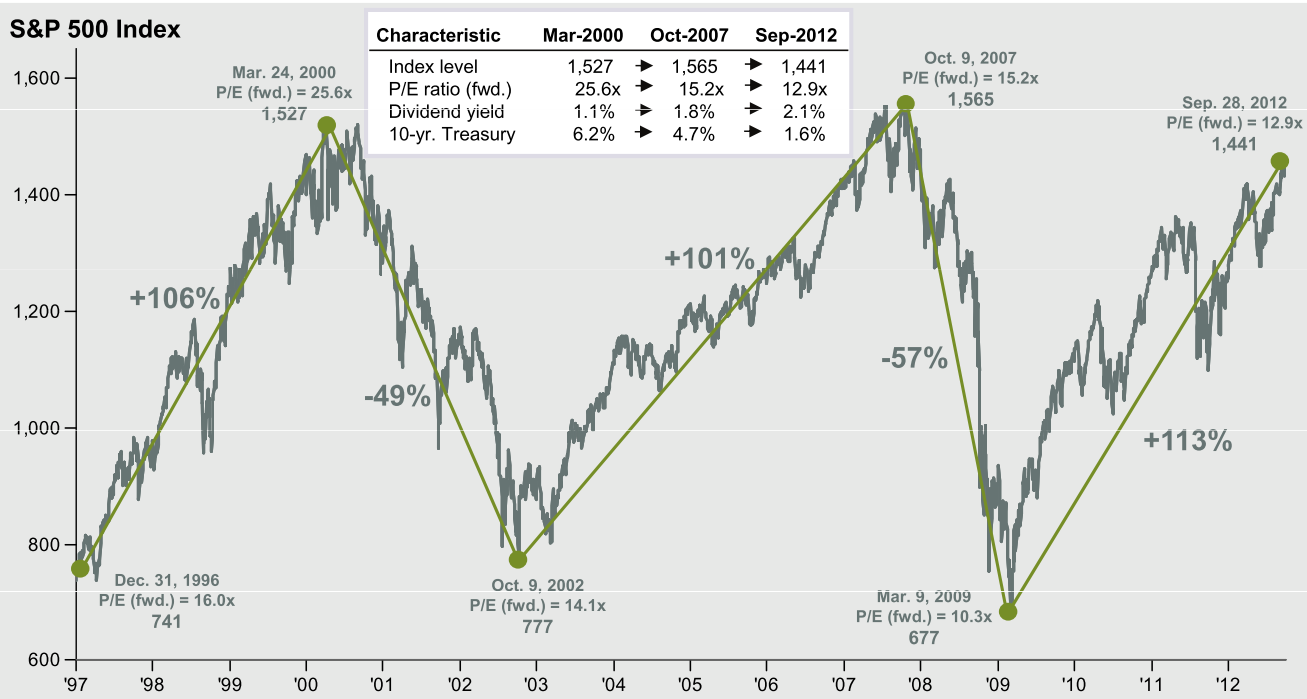

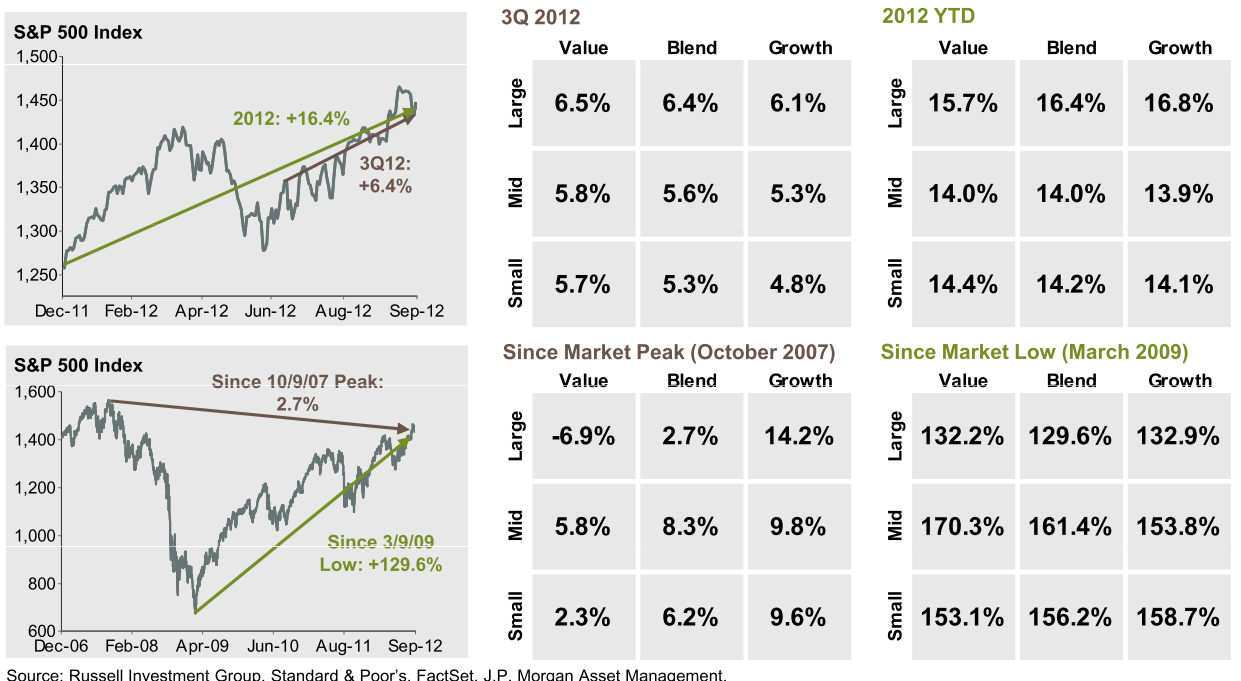

| S&P 500 Index at Inflection Points, Market Returns Posted: 02 Oct 2012 06:30 AM PDT My favorite quarterly chart book is out via JPMorgan. Here are two charts to tease you — go download the entire desk here.

S&P500 Index at Inflection Points ~~~ Market Returns Q3, 2012 Chart reflects index levels (price only). All returns and annotations reflect total returns, including dividends. (Data updated as of 9/30/12).

Source: JPMorgan |

| Posted: 02 Oct 2012 05:58 AM PDT Following yesterday’s story that Spain is on the cusp of finally asking for help with German reluctance to agree, the Spanish Economic Minister after meeting with EU head Rehn yesterday said they are still analyzing the situation and “it will take the best decision for the interests of the Spanish economy and the whole of the euro zone.” Spain knows what conditions are expected from the EU and now seem to be studying how involved the ECB will be. Spanish stocks and bonds are rallying in the belief that we’re very close to finally getting on with this inevitable bailout. At the same time, we must get clarity on how the ESM will be utilized in capitalizing Spanish banks.

Of note elsewhere, the RB of Australia unexpectedly cut interest rates by 25 bps to 3.25% and the ASX responded with a 1% rally and the Aussie is near a 1 month low vs the US$. The RBA said “the growth outlook for next yr looked a little weaker, while inflation was expected to be consistent with the target.” The RBA had rates at 7.25% before the debt crisis then cut them to 3% by Apr ’09. Rates went up to 4.75% and now back to 3.25%. If there is one thing separating the RBA from other central banks is that REAL rates always stay positive. South Korea’s Sept Mfr’g PMI fell to 45.7 from 47.5, the lowest since early ’09. |

| Five Questions about the Federal Reserve and Monetary Policy Posted: 02 Oct 2012 05:00 AM PDT Five Questions about the Federal Reserve and Monetary Policy

Good afternoon. I am pleased to be able to join the Economic Club of Indiana for lunch today. I note that the mission of the club is “to promote an interest in, and enlighten its membership on, important governmental, economic and social issues.” I hope my remarks today will meet that standard. Before diving in, I’d like to thank my former colleague at the White House, Al Hubbard, for helping to make this event possible. As the head of the National Economic Council under President Bush, Al had the difficult task of making sure that diverse perspectives on economic policy issues were given a fair hearing before recommendations went to the President. Al had to be a combination of economist, political guru, diplomat, and traffic cop, and he handled it with great skill. My topic today is “Five Questions about the Federal Reserve and Monetary Policy.” I have used a question-and-answer format in talks before, and I know from much experience that people are eager to know more about the Federal Reserve, what we do, and why we do it. And that interest is even broader than one might think. I’m a baseball fan, and I was excited to be invited to a recent batting practice of the playoff-bound Washington Nationals. I was introduced to one of the team’s star players, but before I could press my questions on some fine points of baseball strategy, he asked, “So, what’s the scoop on quantitative easing?” So, for that player, for club members and guests here today, and for anyone else curious about the Federal Reserve and monetary policy, I will ask and answer these five questions:

What Are the Fed’s Objectives, and How Is It Trying to Meet Them? As the nation’s central bank, the Federal Reserve is charged with promoting a healthy economy–broadly speaking, an economy with low unemployment, low and stable inflation, and a financial system that meets the economy’s needs for credit and other services and that is not itself a source of instability. We pursue these goals through a variety of means. Together with other federal supervisory agencies, we oversee banks and other financial institutions. We monitor the financial system as a whole for possible risks to its stability. We encourage financial and economic literacy, promote equal access to credit, and advance local economic development by working with communities, nonprofit organizations, and others around the country. We also provide some basic services to the financial sector–for example, by processing payments and distributing currency and coin to banks. But today I want to focus on a role that is particularly identified with the Federal Reserve–the making of monetary policy. The goals of monetary policy–maximum employment and price stability–are given to us by the Congress. These goals mean, basically, that we would like to see as many Americans as possible who want jobs to have jobs, and that we aim to keep the rate of increase in consumer prices low and stable. In normal circumstances, the Federal Reserve implements monetary policy through its influence on short-term interest rates, which in turn affect other interest rates and asset prices.1 Generally, if economic weakness is the primary concern, the Fed acts to reduce interest rates, which supports the economy by inducing businesses to invest more in new capital goods and by leading households to spend more on houses, autos, and other goods and services. Likewise, if the economy is overheating, the Fed can raise interest rates to help cool total demand and constrain inflationary pressures. Following this standard approach, the Fed cut short-term interest rates rapidly during the financial crisis, reducing them to nearly zero by the end of 2008–a time when the economy was contracting sharply. At that point, however, we faced a real challenge: Once at zero, the short-term interest rate could not be cut further, so our traditional policy tool for dealing with economic weakness was no longer available. Yet, with unemployment soaring, the economy and job market clearly needed more support. Central banks around the world found themselves in a similar predicament. We asked ourselves, “What do we do now?” To answer this question, we could draw on the experience of Japan, where short-term interest rates have been near zero for many years, as well as a good deal of academic work. Unable to reduce short-term interest rates further, we looked instead for ways to influence longer-term interest rates, which remained well above zero. We reasoned that, as with traditional monetary policy, bringing down longer-term rates should support economic growth and employment by lowering the cost of borrowing to buy homes and cars or to finance capital investments. Since 2008, we’ve used two types of less-traditional monetary policy tools to bring down longer-term rates. The first of these less-traditional tools involves the Fed purchasing longer-term securities on the open market–principally Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by government-sponsored enterprises such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Fed’s purchases reduce the amount of longer-term securities held by investors and put downward pressure on the interest rates on those securities. That downward pressure transmits to a wide range of interest rates that individuals and businesses pay. For example, when the Fed first announced purchases of mortgage-backed securities in late 2008, 30-year mortgage interest rates averaged a little above 6percent; today they average about 3-1/2 percent. Lower mortgage rates are one reason for the improvement we have been seeing in the housing market, which in turn is benefiting the economy more broadly. Other important interest rates, such as corporate bond rates and rates on auto loans, have also come down. Lower interest rates also put upward pressure on the prices of assets, such as stocks and homes, providing further impetus to household and business spending. The second monetary policy tool we have been using involves communicating our expectations for how long the short-term interest rate will remain exceptionally low. Because the yield on, say, a five-year security embeds market expectations for the course of short-term rates over the next five years, convincing investors that we will keep the short-term rate low for a longer time can help to pull down market-determined longer-term rates. In sum, the Fed’s basic strategy for strengthening the economy–reducing interest rates and easing financial conditions more generally–is the same as it has always been. The difference is that, with the short-term interest rate nearly at zero, we have shifted to tools aimed at reducing longer-term interest rates more directly. Last month, my colleagues and I used both tools–securities purchases and communications about our future actions–in a coordinated way to further support the recovery and the job market. Why did we act? Though the economy has been growing since mid-2009 and we expect it to continue to expand, it simply has not been growing fast enough recently to make significant progress in bringing down unemployment. At 8.1 percent, the unemployment rate is nearly unchanged since the beginning of the year and is well above normal levels. While unemployment has been stubbornly high, our economy has enjoyed broad price stability for some time, and we expect inflation to remain low for the foreseeable future. So the case seemed clear to most of my colleagues that we could do more to assist economic growth and the job market without compromising our goal of price stability. Specifically, what did we do? On securities purchases, we announced that we would buy mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by the government-sponsored enterprises at a rate of $40 billion per month. Those purchases, along with the continuation of a previous program involving Treasury securities, mean we are buying $85 billion of longer-term securities per month through the end of the year. We expect these purchases to put further downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, including mortgage rates. To underline the Federal Reserve’s commitment to fostering a sustainable economic recovery, we said that we would continue securities purchases and employ other policy tools until the outlook for the job market improves substantially in a context of price stability. In the category of communications policy, we also extended our estimate of how long we expect to keep the short-term interest rate at exceptionally low levels to at least mid-2015. That doesn’t mean that we expect the economy to be weak through 2015. Rather, our message was that, so long as price stability is preserved, we will take care not to raise rates prematurely. Specifically, we expect that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the economy strengthens. We hope that, by clarifying our expectations about future policy, we can provide individuals, families, businesses, and financial markets greater confidence about the Federal Reserve’s commitment to promoting a sustainable recovery and that, as a result, they will become more willing to invest, hire and spend. Now, as I have said many times, monetary policy is no panacea. It can be used to support stronger economic growth in situations in which, as today, the economy is not making full use of its resources, and it can foster a healthier economy in the longer term by maintaining low and stable inflation. However, many other steps could be taken to strengthen our economy over time, such as putting the federal budget on a sustainable path, reforming the tax code, improving our educational system, supporting technological innovation, and expanding international trade. Although monetary policy cannot cure the economy’s ills, particularly in today’s challenging circumstances, we do think it can provide meaningful help. So we at the Federal Reserve are going to do what we can do and trust that others, in both the public and private sectors, will do what they can as well. What’s the Relationship between Monetary Policy and Fiscal Policy? In short, monetary policy and fiscal policy involve quite different sets of actors, decisions, and tools. Fiscal policy involves decisions about how much the government should spend, how much it should tax, and how much it should borrow. At the federal level, those decisions are made by the Administration and the Congress. Fiscal policy determines the size of the federal budget deficit, which is the difference between federal spending and revenues in a year. Borrowing to finance budget deficits increases the government’s total outstanding debt. As I have discussed, monetary policy is the responsibility of the Federal Reserve–or, more specifically, the Federal Open Market Committee, which includes members of the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors and presidents of Federal Reserve Banks. Unlike fiscal policy, monetary policy does not involve any taxation, transfer payments, or purchases of goods and services. Instead, as I mentioned, monetary policy mainly involves the purchase and sale of securities. The securities that the Fed purchases in the conduct of monetary policy are held in our portfolio and earn interest. The great bulk of these interest earnings is sent to the Treasury, thereby helping reduce the government deficit. In the past three years, the Fed remitted $200 billion to the federal government. Ultimately, the securities held by the Fed will mature or will be sold back into the market. So the odds are high that the purchase programs that the Fed has undertaken in support of the recovery will end up reducing, not increasing, the federal debt, both through the interest earnings we send the Treasury and because a stronger economy tends to lead to higher tax revenues and reduced government spending (on unemployment benefits, for example). Even though our activities are likely to result in a lower national debt over the long term, I sometimes hear the complaint that the Federal Reserve is enabling bad fiscal policy by keeping interest rates very low and thereby making it cheaper for the federal government to borrow. I find this argument unpersuasive. The responsibility for fiscal policy lies squarely with the Administration and the Congress. At the Federal Reserve, we implement policy to promote maximum employment and price stability, as the law under which we operate requires. Using monetary policy to try to influence the political debate on the budget would be highly inappropriate. For what it’s worth, I think the strategy would also likely be ineffective: Suppose, notwithstanding our legal mandate, the Federal Reserve were to raise interest rates for the purpose of making it more expensive for the government to borrow. Such an action would substantially increase the deficit, not only because of higher interest rates, but also because the weaker recovery that would result from premature monetary tightening would further widen the gap between spending and revenues. Would such a step lead to better fiscal outcomes? It seems likely that a significant widening of the deficit–which would make the needed fiscal actions even more difficult and painful–would worsen rather than improve the prospects for a comprehensive fiscal solution. I certainly don’t underestimate the challenges that fiscal policymakers face. They must find ways to put the federal budget on a sustainable path, but not so abruptly as to endanger the economic recovery in the near term. In particular, the Congress and the Administration will soon have to address the so-called fiscal cliff, a combination of sharply higher taxes and reduced spending that is set to happen at the beginning of the year. According to the Congressional Budget Office and virtually all other experts, if that were allowed to occur, it would likely throw the economy back into recession. The Congress and the Administration will also have to raise the debt ceiling to prevent the Treasury from defaulting on its obligations, an outcome that would have extremely negative consequences for the country for years to come. Achieving these fiscal goals would be even more difficult if monetary policy were not helping support the economic recovery. What Is the Risk that the Federal Reserve’s Monetary Policy Will Lead to Inflation? With monetary policy being so accommodative now, though, it is not unreasonable to ask whether we are sowing the seeds of future inflation. A related question I sometimes hear–which bears also on the relationship between monetary and fiscal policy, is this: By buying securities, are you “monetizing the debt”–printing money for the government to use–and will that inevitably lead to higher inflation? No, that’s not what is happening, and that will not happen. Monetizing the debt means using money creation as a permanent source of financing for government spending. In contrast, we are acquiring Treasury securities on the open market and only on a temporary basis, with the goal of supporting the economic recovery through lower interest rates. At the appropriate time, the Federal Reserve will gradually sell these securities or let them mature, as needed, to return its balance sheet to a more normal size. Moreover, the way the Fed finances its securities purchases is by creating reserves in the banking system. Increased bank reserves held at the Fed don’t necessarily translate into more money or cash in circulation, and, indeed, broad measures of the supply of money have not grown especially quickly, on balance, over the past few years. For controlling inflation, the key question is whether the Federal Reserve has the policy tools to tighten monetary conditions at the appropriate time so as to prevent the emergence of inflationary pressures down the road. I’m confident that we have the necessary tools to withdraw policy accommodation when needed, and that we can do so in a way that allows us to shrink our balance sheet in a deliberate and orderly way. For example, the Fed can tighten policy, even if our balance sheet remains large, by increasing the interest rate we pay banks on reserve balances they deposit at the Fed. Because banks will not lend at rates lower than what they can earn at the Fed, such an action should serve to raise rates and tighten credit conditions more generally, preventing any tendency toward overheating in the economy. Of course, having effective tools is one thing; using them in a timely way, neither too early nor too late, is another. Determining precisely the right time to “take away the punch bowl” is always a challenge for central bankers, but that is true whether they are using traditional or nontraditional policy tools. I can assure you that my colleagues and I will carefully consider how best to foster both of our mandated objectives, maximum employment and price stability, when the time comes to make these decisions. How Does the Fed’s Monetary Policy Affect Savers and Investors? However, I would encourage you to remember that the current low levels of interest rates, while in the first instance a reflection of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy, are in a larger sense the result of the recent financial crisis, the worst shock to this nation’s financial system since the 1930s. Interest rates are low throughout the developed world, except in countries experiencing fiscal crises, as central banks and other policymakers try to cope with continuing financial strains and weak economic conditions. A second observation is that savers often wear many economic hats. Many savers are also homeowners; indeed, a family’s home may be its most important financial asset. Many savers are working, or would like to be. Some savers own businesses, and–through pension funds and 401(k) accounts–they often own stocks and other assets. The crisis and recession have led to very low interest rates, it is true, but these events have also destroyed jobs, hamstrung economic growth, and led to sharp declines in the values of many homes and businesses. What can be done to address all of these concerns simultaneously? The best and most comprehensive solution is to find ways to a stronger economy. Only a strong economy can create higher asset values and sustainably good returns for savers. And only a strong economy will allow people who need jobs to find them. Without a job, it is difficult to save for retirement or to buy a home or to pay for an education, irrespective of the current level of interest rates. The way for the Fed to support a return to a strong economy is by maintaining monetary accommodation, which requires low interest rates for a time. If, in contrast, the Fed were to raise rates now, before the economic recovery is fully entrenched, house prices might resume declines, the values of businesses large and small would drop, and, critically, unemployment would likely start to rise again. Such outcomes would ultimately not be good for savers or anyone else. How Is the Federal Reserve Held Accountable in a Democratic Society? The Federal Reserve was created by the Congress, now almost a century ago. In the Federal Reserve Act and subsequent legislation, the Congress laid out the central bank’s goals and powers, and the Fed is responsible to the Congress for meeting its mandated objectives, including fostering maximum employment and price stability. At the same time, the Congress wisely designed the Federal Reserve to be insulated from short-term political pressures. For example, members of the Federal Reserve Board are appointed to staggered, 14-year terms, with the result that some members may serve through several Administrations. Research and practical experience have established that freeing the central bank from short-term political pressures leads to better monetary policy because it allows policymakers to focus on what is best for the economy in the longer run, independently of near-term electoral or partisan concerns. All of the members of the Federal Open Market Committee take this principle very seriously and strive always to make monetary policy decisions based solely on factual evidence and careful analysis. It is important to keep politics out of monetary policy decisions, but it is equally important, in a democracy, for those decisions–and, indeed, all of the Federal Reserve’s decisions and actions–to be undertaken in a strong framework of accountability and transparency. The American people have a right to know how the Federal Reserve is carrying out its responsibilities and how we are using taxpayer resources. One of my principal objectives as Chairman has been to make monetary policy at the Federal Reserve as transparent as possible. We promote policy transparency in many ways. For example, the Federal Open Market Committee explains the reasons for its policy decisions in a statement released after each regularly scheduled meeting, and three weeks later we publish minutes with a detailed summary of the meeting discussion. The Committee also publishes quarterly economic projections with information about where we anticipate both policy and the economy will be headed over the next several years. I hold news conferences four times a year and testify often before congressional committees, including twice-yearly appearances that are specifically designated for the purpose of my presenting a comprehensive monetary policy report to the Congress. My colleagues and I frequently deliver speeches, such as this one, in towns and cities across the country. The Federal Reserve is also very open about its finances and operations. The Federal Reserve Act requires the Federal Reserve to report annually on its operations and to publish its balance sheet weekly. Similarly, under the financial reform law enacted after the financial crisis, we publicly report in detail on our lending programs and securities purchases, including the identities of borrowers and counterparties, amounts lent or purchased, and other information, such as collateral accepted. In late 2010, we posted detailed information on our public website about more than 21,000 individual credit and other transactions conducted to stabilize markets during the financial crisis. And, just last Friday, we posted the first in an ongoing series of quarterly reports providing a great deal of information on individual discount window loans and securities transactions. The Federal Reserve’s financial statement is audited by an independent, outside accounting firm, and an independent Inspector General has wide powers to review actions taken by the Board. Importantly, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has the ability to–and does–oversee the efficiency and integrity of all of our operations, including our financial controls and governance. While the GAO has access to all aspects of the Fed’s operations and is free to criticize or make recommendations, there is one important exception: monetary policymaking. In the 1970s, the Congress deliberately excluded monetary policy deliberations, decisions, and actions from the scope of GAO reviews. In doing so, the Congress carefully balanced the need for democratic accountability with the benefits that flow from keeping monetary policy free from short-term political pressures. However, there have been recent proposals to expand the authority of the GAO over the Federal Reserve to include reviews of monetary policy decisions. Because the GAO is the investigative arm of the Congress and GAO reviews may be initiated at the request of members of the Congress, these reviews (or the prospect of reviews) of individual policy decisions could be seen, with good reason, as efforts to bring political pressure to bear on monetary policymakers. A perceived politicization of monetary policy would reduce public confidence in the ability of the Federal Reserve to make its policy decisions based strictly on what is good for the economy in the longer term. Balancing the need for accountability against the goal of insulating monetary policy from short-term political pressure is very important, and I believe that the Congress had it right in the 1970s when it explicitly chose to protect monetary policy decisionmaking from the possibility of politically motivated reviews. Conclusion Now that I’ve answered questions that I’ve posed to myself, I’d be happy to respond to yours. 1. The Fed has a number of ways to influence short-term rates; basically, they involve steps to affect the supply, and thus the cost, of short-term funding. |

| Big Picture Conference Tickets Reader Contest! Posted: 02 Oct 2012 04:14 AM PDT

To enter: Tweet the link to this page, adding the hashmark #TBPconference. Post this link and hashmark to your Facebook, Google Plus, and LinkedIn pages. (Or Tweet the hashmark + this link: http://thebigpictureconference.eventbrite.com/ ) We will select the 5 people who generate the most retweets of that link by the end of this week, as well as 5 random readers who repost the link. Full conference schedule is after the jump

The Big Picture Conference 8:00 Registration and Breakfast in the Atrium 8:30 Introductions 8:45 Neil Barosfsky 9:30 Dylan Grice in conversation with Rich Yamarone 10:15 –break– 10:30 James O'Shaugnessy 11:15 Barry Ritholtz 12:00 Lunch sponsored by TD Ameritrade served in the Atrium 1:00 David Rosenberg 1:45 Jim Bianco 2:30 Michael Belkin 3:15 –break– 3:30 Bill Gurtin 4:15 Sal Arnuk, Scott Patterson & Josh Brown 5:00 Networking with Wine & Cheese served in the Atrium |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment