The Big Picture |

- Chasing Noise

- Christmas w/ 32 fingers and 8 thumbs

- Succinct Summations of Week’s Events (November 15, 2013)

- EU Fines Financial Institutions Over Fixing Key Benchmarks

- Fun with Corrections!

- 10 Friday AM Reads

- How Do You Define a Bubble? (And are we in one now?)

- Confessions of an Institutional Investor

- Heavy Settle: Just A Cost of Doing Business

- The Curious Case of the Yen as a Safe Haven Currency: A Forensic Analysis

| Posted: 07 Dec 2013 02:00 AM PST |

| Christmas w/ 32 fingers and 8 thumbs Posted: 06 Dec 2013 03:30 PM PST Angels We Have Heard on High 2013 Salt Lake & Boise Christmas Shows! http://smarturl.it/tpgtour |

| Succinct Summations of Week’s Events (November 15, 2013) Posted: 06 Dec 2013 12:30 PM PST Succinct Summations week ending November 15, 2013. Positives:

Negatives:

Thanks, Batman! |

| EU Fines Financial Institutions Over Fixing Key Benchmarks Posted: 06 Dec 2013 11:30 AM PST From the Wall Street Journal:

Source: WSJ |

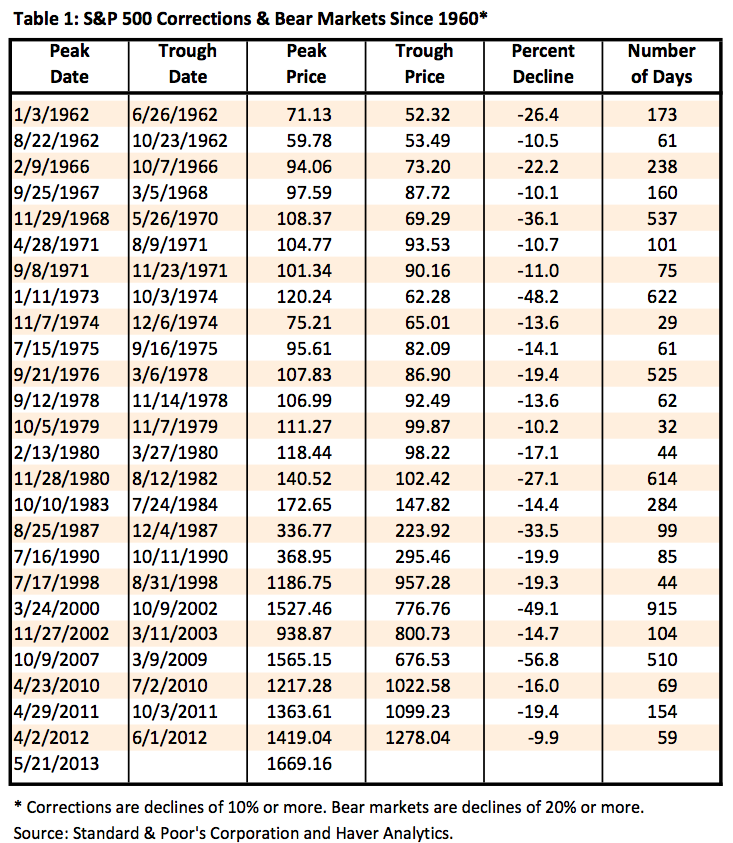

| Posted: 06 Dec 2013 09:54 AM PST click for ginormous table

In this morning's discussion about defining bubbles, a reader made an interesting a posteriori statement: You can tell a bubble after a market has "dived much lower." That sent me hunting for some data as to how often markets actually dive. This table is the result of that quick hunt: Dr. Ed Yardeni's discussion of "S&P 500 Bear Markets & Corrections.” It turns out that these sorts of events are more common than one might have imagined. Defining a correction as a 10 percent or greater drop and a bear market as a 20 percent or worse fall, Yardeni identified 25 such "dives" since 1960. It is interesting to note that we seem to average one of these events (correction or bear market) about every two years. Continues here |

| Posted: 06 Dec 2013 06:52 AM PST My end of week reading materials:

Continues here |

| How Do You Define a Bubble? (And are we in one now?) Posted: 06 Dec 2013 05:00 AM PST

Fridays are the day I like to wax philosophical about all things market related, with an emphasis on the failings of your wetware. This week is no different. The motivation for this week's musings comes from the quote above, courtesy of Clifford Asness, quant analyst and founder of AQR Capital Management. In the Financial Analysts Journal, Asness published a list of his "Top 10 Peeves." I often find myself both intrigued by and in disagreement with Mr. Asness, on matters of economics, politics, and central bankers. (See QE = Currency Debasement and Inflation). However, in his list of peeves, I found myself in utter agreement on the question of whether or not current markets are a bubble. Indeed, I especially found compelling his definition of how to define an equity bubble: "A price that no reasonable future outcome can justify." Now, before we proceed, allow me to share with you a few words about "Question Framing." It is something every first year law student learns. In the art of rhetoric, a properly framed question wins the debate before it even begins. Hence, if you accept a definition of a bubble as defined by Asness, the discussion is more or less already over. Such is the power of framing.

Continues here

|

| Confessions of an Institutional Investor Posted: 06 Dec 2013 04:00 AM PST Josh here – the other day I did a post about the amazing complexity and obsession with tail risk that’s caused so many professionally-managed investment pools to miss the market over the last few years (see: I don’t understand). Every general fights the last war, as they say, and a portfolio geared toward having a 2008-like event every year is a loser. Why invest at all if that’s your expectation? I was inundated with responses to this – from professional investors to fiduciaries who sit on board and councils to my colleagues who advise these gargantuan pools of assets. One incredible response I share with you below. I am leaving the author of this anonymous given their current position, but this is about as raw and honest a take from the inside as you will ever come across. No one working in the field would ever be able to say this out loud. The intent of this author is to (hopefully) influence the current investment management debate. At the institution the author works for, no one is interested in deviating from the status quo, no one wants the risk of picking their heads up and trying something new. The author believes that the consequences of these systemically failed investment policies will ultimately represent a tragedy of lost opportunity and perhaps even unfunded needs. Enjoy! – JB *** I’ve spent my entire career managing institutional portfolios for pensions, endowments and foundations. A few have used a simple, conventional approach while the majority have used the more complex, alternative model that is so popular these days. My current job is with a large fund that uses a complex approach with a focus on downside volatility and the use of hedge funds and private investments. This experience has cemented my opinion that the simple approach is just plain better. I have become extremely disenchanted with the way that the institutions manage their portfolios today. There are many organizations with large portfolios that could benefit from a more conventional philosophy. Many of my peers in the institutional investment industry that I talk to have up to 50, 60 even 70% of their portfolios in alternative investments. This is a recipe for disaster. The high fees, under performance, leverage and lack of transparency for this investing style has been well documented over the past few years, but I have seen other risks above and beyond these issues. Making contributions to hedge funds is easy. They want your money, so you can usually invest on a monthly basis without much notice. But try getting your money out. You usually need at least 90 days' notice and even then you can only redeem on a quarterly or annual basis. If you decide to cut ties with the fund altogether and redeem all of your capital you typically only get 80-90% of your money back from the hedge fund at redemption. The other 10-20% "holdback" doesn’t come back to you until the hedge fund's annual audit which could be up to a year later. So you are forced to sit and wait as your money earns nothing while they make sure the NAV is correct. Contrast this with index funds and ETFs that are priced every second of the trading day. If your hedge fund closes for any reason you get to see the true colors of the illiquid crap these guys are really investing in. Hedge funds can close because of the loss of large investors, untimely investments or simply bored managers that have more than enough money and are sick of meeting client expectations. Our institution was invested in a hedge fund that decided to return capital to investors. They gave us the choice of taking a huge write-down up front or getting the money back as the investments were sold off. We decided to wait and it ended up taking four years to get the entire investment back. And each time they sent chunks of money back the remaining funds got marked down even further. This is a huge opportunity cost. To reduce the risk of a blow-up like this, institutions diversify among multiple hedge funds and strategies, which only increases the likelihood of picking below average funds. Funds normally have at least a 1 year lock-up with your initial investment but it's possible that the lock-up can be 3-5 years in some cases before you can pull your money out. I also witnessed multiple funds side pocket hard to value positions or lock up all investments during the financial crisis. You tell me whether it's worth it to pay 2 & 20 or even more for this deal. I’ve done due diligence on some hedge funds with fees consisting of expenses & 30. Those expenses can run in upwards of 6-8% in good years. So, it could be an 8% management fee & 30% of profits. Private equity also comes with huge opportunity costs. You don't simply hand over the amount you commit to the fund on day one and start investing. With extensions, the investment period could last up to 10 years. How is the original investment thesis still valid after a decade? And what do you do with your money while you wait for it to get called by the fund? Hold cash? Index funds? Plus, you only get about 2 weeks' notice before a capital call is due for investment with no idea about the size so you cannot plan your liquidity ahead of time. PE fees are a sweet deal for the managers too. With the majority of funds, you don't pay management fees on your invested capital. That would make too much sense. You pay on your committed capital. So if you have $30 million committed to a fund but they only call $500,000 in year one, your 2% management fee is over 100% of invested capital. Sounds reasonable, right? Especially when most PE funds can't outperform a simple small cap value ETF. You also must diversify among PE funds by vintage year and strategy to avoid having a single fund blow-up. More chances to be wrong. And good luck finding a PE fund that doesn't claim to be top quartile. Somehow they think they're all top quartile. So why do most institutions in invest this way? 1. It's Interesting What sounds more stimulating as an allocator of capital? a) Traveling to New York, Silicon Valley and London for "due diligence" trips to meet with hedge fund, private equity and venture capital managers, getting wined and dined with free food and booze while getting to hear about complicated strategies, alpha, new technologies and 'what sets us apart.' or b) Finding undervalued asset classes, markets and sectors at a low cost, to achieve a broad diversification and earn multiple streams of beta. You can imagine why most institutional investors choose option a). Don't get me wrong, these trips are a great perk of the job, but I'm not sure how valuable they are for the organization. 2. They Think It's Their Job to Outperform Most institutional investors assume, "My job is to outperform the markets or my benchmark and earn a performance bonus." This is the wrong way to look at a portfolio. Setting a broadly diversified asset allocation, making good decisions, rebalancing to undervalued assets even when it doesn’t feel right, reaching the goals of the organization, reducing fee drag, ensuring liquidity for short-term needs and remembering your time horizon and risk profile should be your job. You can add value without constantly searching for uncorrelated alpha with low downside volatility. The boards at most pensions, endowments and foundations don't help either. They all go right along with the herd mentality. Most are very successful in business, ultra-competitive and want nothing more than to beat the performance of Harvard and Yale. Everyone wants to beat everyone else even with different agendas and somehow complex becomes the norm. 3. They Assume Complex Must be Better The investors that run these portfolios are highly educated individuals who are very intelligent. It's hard for them to admit that the simple solution makes the most sense. Being able to understand complex strategies makes them think they are superior to index funds and ETFs. There is false sense of security when you spend your time talking with brilliant, wealthy alternative managers. I've been in a number of meetings with active managers or consultants who have said the only clients they have lost left to invest with index funds. They wear this fact like a badge of honor. Everyone shares a laugh at the poor investors earning low-cost, market returns. They fail to acknowledge study after study that proves index fund superiority. The assumption that complex financial markets require complex solutions is the first response for institutional investors. But new and exciting is not the same thing as useful. Value at Risk (VAR) and PhD's running risk management models all work until they don't. This is especially true with complex strategies that are impossible to track correctly because of their lack of transparency. You also miss out on the opportunity to rebalance during periods of increased volatility, which is one of the biggest benefits of a more conventional approach. Alternative managers call it forming a long-term partnership, but all it means is less worry for them of the investors using their funds as an ATM when they need the cash the most. Illiquidity gives you the chance to outperform but the obligation to pay higher fees either way. The need to be much better than average to justify the higher fees you're paying leads to extreme results which makes it difficult to maintain a consistent approach. And the loss of the diversification and correlation benefits when you need them the most is sacrificed for increased monitoring costs by having more complex strategies. Most institutional investors have an offshoot of the "Yale Model" that's described by David Swensen in his book, Pioneering Portfolio Management. It serves as the de-facto institutional investment community handbook. Most institutions took his advice on diversification into alternative investments and active management and skipped the most useful advice in the book for 99% of them: "Certainly, the game of active management entices players to enter, offering the often false hope of excess returns. Perhaps those few smart enough to recognize that passive strategies provide a superior alternative believe themselves to be smart enough to beat the market. In any event, deviations from benchmark returns represent an important source of portfolio risk." "Academic research backs up the notion that private equity produces generally mediocre results." "In the context of an extraordinary complex, difficult investing environment, fiduciaries tend to be surprisingly accepting of active management pitches. Institutions all too often pursue the glamorous, exciting (and ultimately costly) hope of market-beating strategies at the expense of reliable, mundane certainty of passive management." "Even if investors could purchase the median result in an alternative asset class, the results would likely disappoint. Longer term median historical returns have lagged comparable marketable security results, both in absolute and risk-adjusted terms." I’ve seen complexity fail over multiple investment cycles in these types of portfolios, but as Keynes told us, "Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for the reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally." Somehow simplicity has become the exception while complexity is now the rule. I believe that meeting long-term spending needs for institutional portfolios and controlling risk can be accomplished through simplicity. That's not to say that it's easy, just less complex. A complicated portfolio relies on the hope of being smarter than your investing peers and the markets while taking on added risks. We all know hope is not an investment strategy. I wish I had an answer for a catalyst for these changes to come about but I'm afraid it's going to take a couple of cycles for this to happen. *** Excellently stated. What do you think? Read Also: |

| Heavy Settle: Just A Cost of Doing Business Posted: 06 Dec 2013 03:00 AM PST Corporations pay the nominal price for years of systemic fraud. The Daily Show (03:34) |

| The Curious Case of the Yen as a Safe Haven Currency: A Forensic Analysis Posted: 06 Dec 2013 02:00 AM PST |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment