The Big Picture |

- Do Forecasters Believe in Okun’s Law? An Assessment of Unemployment and Output Forecasts

- Nine Surprising Things Jesse Livermore Said

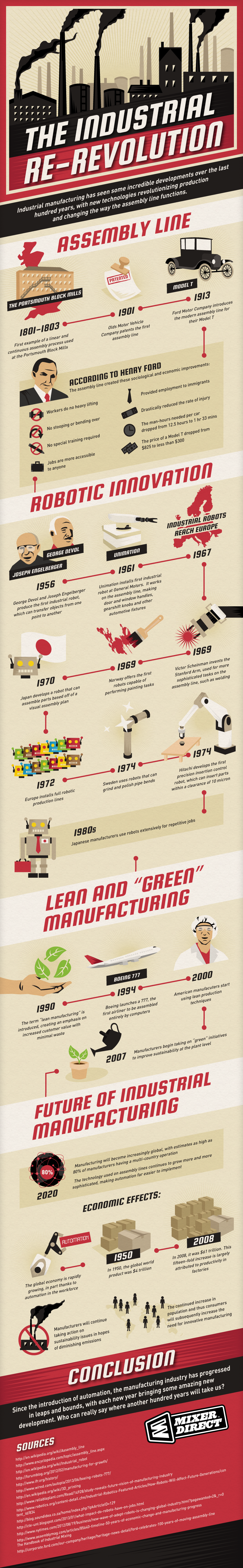

- Industrial Re-Revolution

- When the Consumer is the Consumed

- Seeing the Big Picture

- 10 Mid-Week Reads

- Storm of Stars

| Do Forecasters Believe in Okun’s Law? An Assessment of Unemployment and Output Forecasts Posted: 20 Feb 2014 02:00 AM PST |

| Nine Surprising Things Jesse Livermore Said Posted: 19 Feb 2014 03:00 PM PST There are those who would convince you that it is somehow smart or in your best interest to be manically switching your investments around, back and forth, long and short, on a daily basis. To pay attention to this kind of overstimulation is the height of madness, even for professional traders. The most storied and important trader who ever lived, Jesse Livermore, would be tuning these daily buy and sell calls out were he alive and operating today. Because while he was a trader, he was not of the mindset that there was always some kind of action to be taking. Jesse Livermore's legacy is a bit of a double-edged sword… On the one hand, he was the first to codify the ancient language of supply and demand that is every bit as relevant 100 years later as it was when he first relayed it to biographer Edwin Lefèvre. Livermore himself sums it up thusly: "I learned early that there is nothing new in Wall Street. There can't be because speculation is as old as the hills. Whatever happens in the stock market today has happened before and will happen again. I've never forgotten that." On the other hand, Livermore's undoing came at precisely the moments in which he ignored his own advice. After repeated admonitions about tipsters, for example, Jesse allowed a tip on cotton to lead to a massive loss which grew even larger as he sat on it – violating yet another of his own cardinal rules. And of course, other than for a few moments of temporary triumph in the trading pits and bucket shops of the era, Jesse Livermore was not a happy man. "Things haven't gone well with me," he informed one of his many wives by handwritten note, before putting a bullet through his own head in the cloakroom of the Sherry-Netherland Hotel. But he did leave behind a wealth of knowledge about the art of speculation. His exploits (and cautionary tales of woe) have educated, influenced and inspired every generation of trader since Reminiscences was first published in 1923. In my opinion, some of the most useful bits of knowledge we get from the book concern Jesse's discussion of timeframes and patience. Many traders, particularly rookies, approach the game with the idea that they're supposed to be constantly doing something - in and out, with a trembling finger poised to click the mouse again and again. Consequently, they get on the treadmill of booking wins and losses without ever really moving the needle. They end up with tons of brokerage commissions and taxes to show for their efforts, but not much else. Being a trader doesn't mean one must always be executing a trade, just as being a house painter doesn't mean that every surface needs an endless series of coats. Many rookies are surprised to learn that Livermore, the idol of so many great traders, advocated a lower maintenance, higher patience approach as he matured. In his early days, Livermore was dependent on the short-term funding and scalping activity of the bucket shops. Once he graduated and had his own capital, he was able to lengthen position holding times and could even afford to do nothing for extended periods. Here are nine surprising things Jesse Livermore said regarding excessive trading: 1. "Money is made by sitting, not trading." 2. "It takes time to make money." 3. "It was never my thinking that made the big money for me, it always was sitting." 4. "Nobody can catch all the fluctuations." 5. "The desire for constant action irrespective of underlying conditions is responsible for many losses in Wall Street even among the professionals, who feel that they must take home some money everyday, as though they were working for regular wages." 6. "Buy right, sit tight." 7. "Men who can both be right and sit tight are uncommon." 8. "Don't give me timing, give me time." and finally, the most important thing: 9. "There is a time for all things, but I didn't know it. And that is precisely what beats so many men in Wall Street who are very far from being in the main sucker class. There is the plain fool, who does the wrong thing at all times everywhere, but there is the Wall Street fool, who thinks he must trade all the time. Not many can always have adequate reasons for buying and selling stocks daily – or sufficient knowledge to make his play an intelligent play." Jesse was a trader but he knew the value of staying with positions and sometimes not trading at all. Once he began to follow tips from others or trade when he should have abstained, all of his progress had come undone, and with it, his sanity. We are fortunate to be able to learn from his mistakes and to sidestep the errors that eventually cost him everything. Read Also: *** |

| Posted: 19 Feb 2014 10:00 AM PST

|

| When the Consumer is the Consumed Posted: 19 Feb 2014 09:00 AM PST

When someone tells me that they have abandoned so-called mainstream media, I often envision a person who has pulled his boat to the shore of that proverbial stream to explore alternatives, only to be attacked by savages. But to make this analogy work, I would say that this contrarian news consumer is not aware that the newfound information sources are savages; and he is not immediately attacked. Instead there is an initial curiosity and charm about the savages; and so the consumer happily accepts an invitation to their village. As he consumes everything the savages offer, he thinks himself wiser for his discovery. However, the consumer grows fatter and lazier, unaware that the savages plan to eat him. The consumer becomes the consumed. As both a money manager and a freelance writer, I have the unenviable perspective of seeing the tactics of the savages; uh, I mean financial news sources, which is to steal for their own purposes the attention of the consumer. This also brings to mind a quote from the 20th century psychologist and economist, Herbert Simon, that I share with readers whenever I find the opportunity:

When you pay attention, what is the price? If attention were currency, most human beings would be well below poverty level. The attention theft goes mostly undetected because many consumers that seek information are not aware that, in actuality, it is the source of information that is the seeker, as well as a consumer, albeit higher in the food chain. The unaware hunter will eventually become the hunted. So how do financial media (and almost all media for that matter) hunt their prey? It all begins with the headline:

Note: All of the above are actual headlines I quickly found yesterday on a small handful of financial media sites but I intentionally omitted hyper-links to the content because I did not want to ironically distract from the idea that your attention is constantly at risk of being consumed. It is not just the so-called mainstream media that is the enemy of the thinking person. Any source of information that exists to sell advertising accomplishes its end by means of stealing attention. Therefore its purpose is not to serve the end user, period. Furthermore, there is a proliferation of amateurism in recent years: knowledge and expertise of financial services and products is not necessary to write about them. All that is required is the ability to steal attention, to get that first click on the headline. Once you have arrived at the article or post, the strategy is to keep you there another 10 seconds and then perhaps click on a few other links… mission accomplished. The primary point being made here is that your attention may be the greatest resource you have. Without it, your capacity for good judgment is impaired. To maintain ownership of this resource you must have sufficient awareness of the tactics being used to take it from you. With this awareness, information can become a tool to serve whatever purpose you have for it. If not, it is you that is the tool. To help our fellow readers, what information sources do you believe are some of the most notorious attention thefts? And which sources do you believe are best at providing useful information that is high on facts and low on spin? Kent Thune is the blog author of The Financial Philosopher. You can follow Kent on Twitter @ThinkersQuill. |

| Posted: 19 Feb 2014 05:30 AM PST Robert P. Seawright is the Chief Investment & Information Officer for Madison Avenue Securities, a boutique broker-dealer and investment advisory firm headquartered in San Diego, California. Bob is also a columnist for Research magazine, a Contributing Editor at Portfolioist as well as a contributor to the Financial Times, The Big Picture, The Wall Street Journal's MarketWatch, Pragmatic Capitalism, and Advisor One. ~~~ Barry's wonderful blog – although you may be re-thinking its wonderfulness given that I'm here – is, as you obviously know, called The Big Picture. His idea is to look at the investment universe using a very wide lens for a very broad audience, governed only by "facts, statistics, and informed, data-driven opinions." Most fundamentally, he doesn't want to miss the forest for the trees. He approaches "most investing issues with one foot in the behavioral camp, the other thrown in with the quants." Intriguingly, behavioral finance meets quantitative analysis head-on when it comes to big picture analysis. In a more perfect world – like the false one in which economists tend to live – investors would examine each new investment opportunity by evaluating it in context with other current and potential investments, goals, objectives and needs. If the expected return of the opportunity is sufficient on a risk-adjusted basis and if it would improve the investor's position in the aggregate, the investor would then consider buying it (at the right price, though our economist friends seem to think that every price is the right price). Thus the investor would only get utility from the outcome of the investment indirectly, via its contribution to his or her total wealth and overall situation. But none of us is homo economicus. Instead, we tend to spend all our careful analysis on those pesky trees. Narrow framing is the behavioral phenomenon whereby, when people are offered a new opportunity, they evaluate it in isolation, separately from their other holdings, opportunities and risks as well as their overall situation. In economic terms, they act as if they get utility directly from the outcome of the investment decision, even if and when the investment is just one of many that determines portfolio performance and risk. They also tend to put disproportionate emphasis on short-term returns. As so often happens in behavioral finance, the classic demonstration of this concept is found in the work of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. In this instance, it comes from The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice (1981). Kahneman and Tversky asked subjects the following question. Imagine that you face the following pair of concurrent decisions. First examine both decisions, then indicate the options you prefer: Decision (i). Choose between:

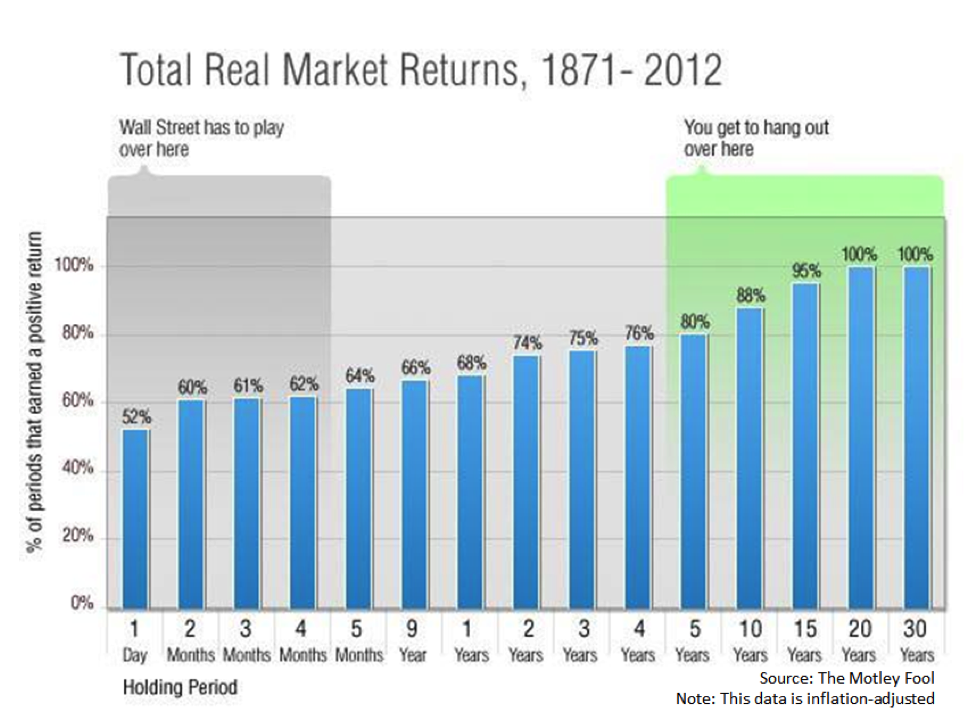

They reported that 84 percent of subjects chose A and that 87 percent chose D. Moreover, 73 percent of subjects chose the combination of A and D, which offered, in the aggregate, a 25 percent chance to win $240 and a 75 percent chance to lose $760 – even though the B and C combo offered a better outcome, namely a 25 percent chance to win $250 and a 75 percent chance to lose $750. Since the subjects were students at Stanford University and at the University of British Columbia, the problem shouldn't have been too difficult (though my younger son – who went to Berkeley and denigrates all things 'furd – will surely disagree). Thus instead of focusing on the combined outcome of decisions (i) and (ii), subjects focused on the outcome of each decision separately. Indeed, subjects who are asked only about decision (i) did overwhelmingly choose A and subjects asked only about decision (ii) did overwhelmingly choose D. Accordingly, the subjects didn't maximize aggregate utility in a rational manner (shocking, I know). One practical investment tidbit to take from this cognitive shortcoming is that investors tend to like diversification more in theory than in practice. They like the idea of diversification preventing loss but hate the idea (as in 2013) of diversification suppressing gain. Every money manager has met with a client after a great year and heard only about the position(s) that didn't do as well rather than the great overall performance. As my wife often tells me (partly in jest), I don't want much, I just want more. A better investment process, then, is careful to evaluate every potential investment within the context of the entire portfolio as well as the investor's overall situation. When we don't and evaluate opportunities too narrowly, we can miss out on diversification opportunities. We can also miss out on quality opportunities in that we see too much risk even though the risk is much more limited within the context of the whole. We might even end up with an investment that, in large measure at least, potentially cancels another out or works against the investor's overall objectives. We also tend to invoke too narrow a frame in terms of time. When we evaluate potential performance over too narrow a time frame, we will surely miss some great opportunities. Axiomatically, long-term investors shouldn't care what happens except over the long-term. But we do. And the time horizon we focus on makes a big difference to how we perceive and evaluate an investment.

For example (see above), major equity indices post losses in nearly half of one-day periods and in about 40 percent of one, two and three-month periods – which makes them seem fairly dangerous, especially because we tend to be so risk and loss averse. But over five years we only observe losses about 20 percent of the time and almost never over 20 years and longer, even when adjusted for inflation. Many investors actually take too little risk because of a myopically narrow frame of reference. In other words, we misalign our decision frame to our objectives. In practical terms, the problem is that we focus too much on yes or no? and not enough on a wider range of choices. As well as looking at individual opportunities, we should also consider (for example) whether another sector or even another asset class might work better. For even professional investors, narrow framing means too much analysis along the lines of Do I like it or not, and not enough along the lines of What am I/should I be after and does this opportunity really help in that regard? When I (long ago, now) worked on a big-time Wall Street trading desk, our focus was almost exclusively on whether the security we were pushing at the time was rich or cheap (or at least upon whether we could construct an argument to make it seem rich or cheap). It was all about the trade today. Smart investors will take a much wider frame of reference and will focus instead upon the longer-term, value, risk (and not just volatility) in the context of his or her goals, objectives and needs. In other words, we should always focus on the big picture.

|

| Posted: 19 Feb 2014 04:00 AM PST Good Wednesday morn . . . Some beach reading for you:

What are you reading?

Gold Above Its 200 DMA |

| Posted: 19 Feb 2014 03:00 AM PST

From Wired:

|

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment