The Big Picture |

- A Limited Central Bank

- 75th Anniversary of Lou Gehrig’s speech

- Succinct Summation of Week’s Events 7.3.14

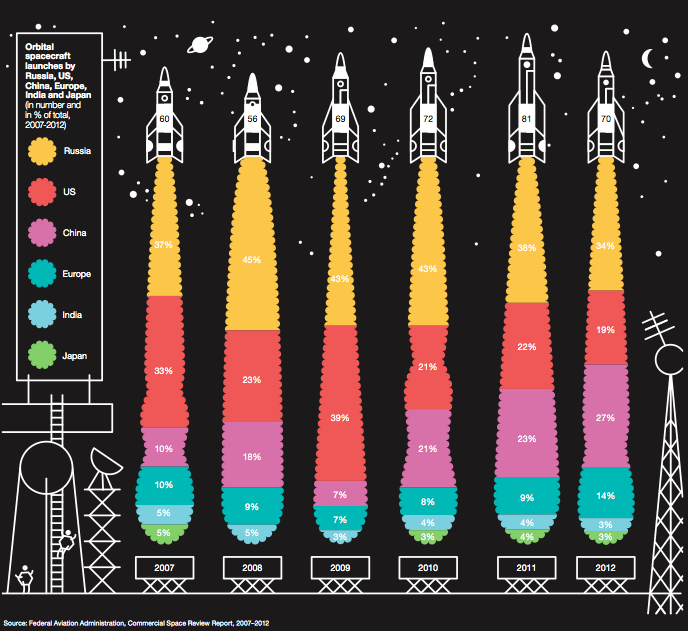

- Orbital spacecraft launches by Russia, US, China, Europe, India & Japan

- 10 Thursday AM Reads

- Job Separation Rate Shows Economic Shifts

- Top Payers of Fines and Settlements to U.S. Authorities

- Chair Janet L. Yellen: Monetary Policy and Financial Stability

| Posted: 04 Jul 2014 02:00 AM PDT A Limited Central Bank As the Fed begins its 100th anniversary year, I believe it is entirely appropriate to reflect on its history and its future. At the same time, we need to reflect on what I believe is the Federal Reserve's essential role and how it might be improved as an institution to better fulfill that role.1 Douglass C. North was cowinner of the 1993 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on the role that institutions play in economic growth.2 North argued that institutions were deliberately devised to constrain interactions among parties both public and private. In the spirit of North's work, one theme of this essay will focus on the fact that the institutional structure of the central bank matters. The central bank's goals and objectives, its framework for implementing policy, and its governance structure all affect its performance. Central banks have been around for a long time, but they have clearly evolved as economies and governments have changed. Most countries today operate under a fiat money regime, in which a nation's currency has value because the government says it does. Central banks are usually given the responsibility to protect and preserve the value or purchasing power of the currency.3 In the U.S., the Fed does so by buying or selling assets in order to manage the growth of money and credit. The ability to buy and sell assets gives the Fed considerable power to intervene in financial markets not only through the quantity of its transactions but also through the types of assets it can buy and sell. Thus, it is entirely appropriate that governments establish their central banks with limits that constrain the actions of the central bank to one degree or another. Yet, in recent years, we have seen many of the explicit and implicit limits stretched. The Fed and many other central banks have taken extraordinary steps to address a global financial crisis and the ensuing recession. These steps have challenged the accepted boundaries of central banking and have been both applauded and denounced. For example, the Fed has adopted unconventional largescale asset purchases to increase accommodation after it reduced its conventional policy tool — the federal funds rate — to near zero. These asset purchases have led to the creation of trillions of dollars of reserves in the banking system and have greatly expanded the Fed's balance sheet. But the Fed has done more than just purchase lots of assets; it has altered the composition of its balance sheet through the types of assets it has purchased. I have spoken on a number of occasions about my concerns that these actions to purchase specific (non-Treasury) assets amounted to a form of credit allocation, which targets specific industries, sectors, or firms. These credit policies cross the boundary from monetary policy and venture into the realm of fiscal policy.4 I include in this category the purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) as well as emergency lending under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, in support of the bailouts, most notably of Bear Stearns and AIG. Regardless of the rationale for these actions, one needs to consider the long-term repercussions that such actions may have on the central bank as an institution. As we contemplate what the Fed of the future should look like, I will discuss whether constraints on its goals might help limit the range of objectives it could use to justify its actions. I will also consider restrictions on the types of assets it can purchase to limit its interference with market allocations of scarce capital and generally to avoid engaging in actions that are best left to the fiscal authorities or the markets. I will also touch on governance and accountability of our institution and ways to implement policies that limit discretion and improve outcomes and accountability. Goals and Objectives The Federal Reserve's goals and objectives have evolved over time. When the Fed was first established in 1913, the U.S. and the world were operating under a classical gold standard. Therefore, price stability was not among the stated goals in the original Federal Reserve Act. Indeed, the primary objective in the preamble was to provide an "elastic currency." The gold standard had some desirable features. Domestic and international legal commitments regarding convertibility were important disciplining devices that were essential to the regime's ability to deliver general price stability. The gold standard was a de facto rule that most people understood, and it allowed markets to function more efficiently because the price level was mostly stable. But the international gold standard began to unravel and was abandoned during World War I.5 After the war, efforts to reestablish parity proved disruptive and costly in both economic and political terms. Attempts to reestablish a gold standard ultimately fell apart in the 1930s. As a result, most of the world now operates under a fiat money regime, which has made price stability an important priority for those central banks charged with ensuring the purchasing power of the currency. Congress established the current set of monetary policy goals in 1978. The amended Federal Reserve Act specifies the Fed "shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy's long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates." Since moderate long-term interest rates generally result when prices are stable and the economy is operating at full employment, many have interpreted these goals as a dual mandate with price stability and maximum employment as the focus. Let me point out that the instructions from Congress call for the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to stress the "long run growth" of money and credit commensurate with the economy's "long run potential." There are many other things that Congress could have specified, but it chose not to do so. The act doesn't talk about managing short-term credit allocation across sectors; it doesn't mention inflating housing prices or other asset prices. It also doesn't mention reducing short-term fluctuations in employment. Many discussions about the Fed's mandate seem to forget the emphasis on the long run. The public, and perhaps even some within the Fed, have come to accept as an axiom that monetary policy can and should attempt to manage fluctuations in employment. Rather than simply set a monetary environment "commensurate" with the "long run potential to increase production," these individuals seek policies that attempt to manage fluctuations in employment over the short run. The active pursuit of employment objectives has been and continues to be problematic for the Fed. Most economists are dubious of the ability of monetary policy to predictably and precisely control employment in the short run, and there is a strong consensus that, in the long run, monetary policy cannot determine employment. As the FOMC noted in its statement on longer-run goals adopted in 2012, "the maximum level of employment is largely determined by nonmonetary factors that affect the structure and dynamics of the labor market." In my view, focusing on short-run control of employment weakens the credibility and effectiveness of the Fed in achieving its price stability objective. We learned this lesson most dramatically during the 1970s when, despite the extensive efforts to reduce unemployment, the Fed essentially failed, and the nation experienced a prolonged period of high unemployment and high inflation. The economy paid the price in the form of a deep recession, as the Fed sought to restore the credibility of its commitment to price stability. When establishing the longer-term goals and objectives for any organization, and particularly one that serves the public, it is important that the goals be achievable. Assigning unachievable goals to organizations is a recipe for failure. For the Fed, it could mean a loss of public confidence. I fear that the public has come to expect too much from its central bank and too much from monetary policy, in particular. We need to heed the words of another Nobel Prize winner, Milton Friedman. In his 1967 presidential address to the American Economic Association, he said, "… we are in danger of assigning to monetary policy a larger role than it can perform, in danger of asking it to accomplish tasks that it cannot achieve, and as a result, in danger of preventing it from making the contribution that it is capable of making."6 In the 1970s, we saw the truth in Friedman's earlier admonitions. I think that over the past 40 years, with the exception of the Paul Volcker era, we failed to heed this warning. We have assigned an ever-expanding role for monetary policy, and we expect our central bank to solve all manner of economic woes for which it is ill-suited to address. We need to better align the expectations of monetary policy with what it is actually capable of achieving. The so-called dual mandate has contributed to this expansionary view of the powers of monetary policy. Even though the 2012 statement of objectives acknowledged that it is inappropriate to set a fixed goal for employment and that maximum employment is influenced by many factors, the FOMC's recent policy statements have increasingly given the impression that it wants to achieve an employment goal as quickly as possible.7 I believe that the aggressive pursuit of broad and expansive objectives is quite risky and could have very undesirable repercussions down the road, including undermining the public's confidence in the institution, its legitimacy, and its independence. To put this in different terms, assigning multiple objectives for the central bank opens the door to highly discretionary policies, which can be justified by shifting the focus or rationale for action from goal to goal. I have concluded that it would be appropriate to redefine the Fed's monetary policy goals to focus solely, or at least primarily, on price stability. I base this on two facts: Monetary policy has very limited ability to influence real variables, such as employment. And, in a regime with fiat currency, only the central bank can ensure price stability. Indeed, it is the one goal that the central bank can achieve over the longer run. Governance and Central Bank Independence Even with a narrow mandate to focus on price stability, the institution must be well designed if it is to be successful. To meet even this narrow mandate, the central bank must have a fair amount of independence from the political process so that it can set policy for the long run without the pressure to print money as a substitute for tough fiscal choices. Good governance requires a healthy degree of separation between those responsible for taxes and expenditures and those responsible for printing money. The original design of the Fed's governance recognized the importance of this independence. Consider its decentralized, public-private structure, with Governors appointed by the U.S. President and confirmed by the Senate, and Fed presidents chosen by their boards of directors. This design helps ensure a diversity of views and a more decentralized governance structure that reduces the potential for abuses and capture by special interests or political agendas. It also reinforces the independence of monetary policymaking, which leads to better economic outcomes. Implementing Policy and Limiting Discretion Such independence in a democracy also necessitates that the central bank remain accountable. Its activities also need to be constrained in a manner that limits its discretionary authority. As I have already argued, a narrow mandate is an important limiting factor on an expansionist view of the role and scope for monetary policy. What other sorts of constraints are appropriate on the activities of central banks? I believe that monetary policy and fiscal policy should have clear boundaries.8 Independence is what Congress can and should grant the Fed, but, in exchange for such independence, the central bank should be constrained from conducting fiscal policy. As I have already mentioned, the Fed has ventured into the realm of fiscal policy by its purchase programs of assets that target specific industries and individual firms. One way to circumscribe the range of activities a central bank can undertake is to limit the assets it can buy and hold. In its System Open Market Account, the Fed is allowed to hold only U.S. government securities and securities that are direct obligations of or fully guaranteed by agencies of the United States. But these restrictions still allowed the Fed to purchase large amounts of agency mortgage-backed securities in its effort to boost the housing sector. My preference would be to limit Fed purchases to Treasury securities and return the Fed's balance sheet to an all-Treasury portfolio. This would limit the ability of the Fed to engage in credit policies that target specific industries. As I've already noted, such programs to allocate credit rightfully belong in the realm of the fiscal authorities — not the central bank. A third way to constrain central bank actions is to direct the monetary authority to conduct policy in a systematic, rule-like manner.9 It is often difficult for policymakers to choose a systematic, rule-like approach that would tie their hands and thus limit their discretionary authority. Yet, research has discussed the benefits of rule-like behavior for some time. Rules are transparent and therefore allow for simpler and more effective communication of policy decisions. Moreover, a large body of research emphasizes the important role expectations play in determining economic outcomes. When policy is set systematically, the public and financial market participants can form better expectations about policy. Policy is no longer a source of instability or uncertainty. While choosing an appropriate rule is important, research shows that in a wide variety of models simple, robust monetary policy rules can produce outcomes close to those delivered by each model's optimal policy rule. Systematic policy can also help preserve a central bank's independence. When the public has a better understanding of policymakers' intentions, it is able to hold the central bank more accountable for its actions. And the rule-like behavior helps to keep policy focused on the central bank's objectives, limiting discretionary actions that may wander toward other agendas and goals. Congress is not the appropriate body to determine the form of such a rule. However, Congress could direct the monetary authority to communicate the broad guidelines the authority will use to conduct policy. One way this might work is to require the Fed to publicly describe how it will systematically conduct policy in normal times — this might be incorporated into the semiannual Monetary Policy Report submitted to Congress. This would hold the Fed accountable. If the FOMC chooses to deviate from the guidelines, it must then explain why and how it intends to return to its prescribed guidelines. My sense is that the recent difficulty the Fed has faced in trying to offer clear and transparent guidance on its current and future policy path stems from the fact that policymakers still desire to maintain discretion in setting monetary policy. Effective forward guidance, however, requires commitment to behave in a particular way in the future. But discretion is the antithesis of commitment and undermines the effectiveness of forward guidance. Given this tension, few should be surprised that the Fed has struggled with its communications. What is the answer? I see three: Simplify the goals. Constrain the tools. Make decisions more systematically. All three steps can lead to clearer communications and a better understanding on the part of the public. Creating a stronger policymaking framework will ultimately produce better economic outcomes. Financial Stability and Monetary Policy Before concluding, I would like to say a few words about the role that the central bank plays in promoting financial stability. Since the financial crisis, there has been an expansion of the Fed's responsibilities for controlling macroprudential and systemic risk. Some have even called for an expansion of the monetary policy mandate to include an explicit goal for financial stability. I think this would be a mistake. The Fed plays an important role as the lender of last resort, offering liquidity to solvent firms in times of extreme financial stress to forestall contagion and mitigate systemic risk. This liquidity is intended to help ensure that solvent institutions facing temporary liquidity problems remain solvent and that there is sufficient liquidity in the banking system to meet the demand for currency. In this sense, liquidity lending is simply providing an "elastic currency." Thus, the role of lender of last resort is not to prop up insolvent institutions. However, in some cases during the crisis, the Fed played a role in the resolution of particular insolvent firms that were deemed systemically important financial firms. Subsequently, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act has limited some of the lending actions the Fed can take with individual firms under Section 13(3). Nonetheless, by taking these actions, the Fed has created expectations — perhaps unrealistic ones — about what the Fed can and should do to combat financial instability. Just as it is true for monetary policy, it is important to be clear about the Fed's responsibilities for promoting financial stability. It is unrealistic to expect the central bank to alleviate all systemic risk in financial markets. Expanding the Fed's regulatory responsibilities too broadly increases the chances that there will be short-run conflicts between its monetary policy goals and its supervisory and regulatory goals. This should be avoided, as it could undermine the credibility of the Fed's commitment to price stability. Similarly, the central bank should set boundaries and guidelines for its lending policy that it can credibly commit to follow. If the set of institutions having regular access to the Fed's credit facilities is expanded too far, it will create moral hazard and distort the market mechanism for allocating credit. This can end up undermining the very financial stability that it is supposed to promote. Emergencies can and do arise. If the Fed is asked by the fiscal authorities to intervene by allocating credit to particular firms or sectors of the economy, then the Treasury should take these assets off of the Fed's balance sheet in exchange for Treasury securities. In 2009, I advocated that we establish a new accord between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve that protects the Fed in just such a way.10 Such an arrangement would be similar to the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951 that freed the Fed from keeping the interest rate on longterm Treasury debt below 2.5 percent. It would help ensure that when credit policies put taxpayer funds at risk, they are the responsibility of the fiscal authority — not the Fed. A new accord would also return control of the Fed's balance sheet to the Fed so that it can conduct independent monetary policy. Many observers think financial instability is endemic to the financial industry, and therefore, it must be controlled through regulation and oversight. However, financial instability can also be a consequence of governments and their policies, even those intended to reduce instability. I can think of three ways in which central bank policies can increase the risks of financial instability. First, by rescuing firms or creating the expectation that creditors will be rescued, policymakers either implicitly or explicitly create moral hazard and excessive risking-taking by financial firms. For this moral hazard to exist, it doesn't matter if the taxpayer or the private sector provides the funds. What matters is that creditors are protected, in part, if not entirely. Second, by running credit policies, such as buying huge volumes of mortgage-backed securities that distort market signals or the allocation of capital, policymakers can sow the seeds of financial instability because of the distortions that they create, which in time must be corrected. And third, by taking a highly discretionary approach to monetary policy, policymakers increase the risks of financial instability by making monetary policy uncertain. Such uncertainty can lead markets to make unwise investment decisions — witness the complaints of those who took positions expecting the Fed to follow through with the taper decision in September 2013. The Fed and other policymakers need to think more about the way their policies might contribute to financial instability. I believe that it is important that the Fed take steps to conduct its own policies and to help other regulators reduce the contributions of such policies to financial instability. The more limited role for the central bank I have described here can contribute to such efforts. Conclusion The financial crisis and its aftermath have been challenging times for global economies and their institutions. The extraordinary actions taken by the Fed to combat the crisis and the ensuing recession and to support recovery have expanded the roles assigned to monetary policy. The public has come to expect too much from its central bank. To remedy this situation, I believe it would be appropriate to set four limits on the central bank:

These steps would yield a more limited central bank. In doing so, they would help preserve the central bank's independence, thereby improving the effectiveness of monetary policy, and, at the same time, they would make it easier for the public to hold the Fed accountable for its policy decisions. These changes to the institution would strengthen the Fed for its next 100 years. ENDNOTES 1 This essay is based on a speech by the author, "A Limited Central Bank," presented at the Cato Institute's 31st Annual Monetary Conference, November 14, 2013, in Washington, D.C. The views expressed here are the author's and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve System or the Federal Open Market Committee. |

| 75th Anniversary of Lou Gehrig’s speech Posted: 03 Jul 2014 03:00 PM PDT

|

| Succinct Summation of Week’s Events 7.3.14 Posted: 03 Jul 2014 10:00 AM PDT Succinct Summations for the week ending July 3rd Positives:

Negatives:

Thanks, Batman. |

| Orbital spacecraft launches by Russia, US, China, Europe, India & Japan Posted: 03 Jul 2014 09:00 AM PDT

|

| Posted: 03 Jul 2014 06:30 AM PDT My pre-holiday morning reads (Continues here):

|

| Job Separation Rate Shows Economic Shifts Posted: 03 Jul 2014 04:00 AM PDT |

| Top Payers of Fines and Settlements to U.S. Authorities Posted: 03 Jul 2014 03:00 AM PDT

|

| Chair Janet L. Yellen: Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Posted: 03 Jul 2014 02:00 AM PDT Chair Janet L. Yellen: Monetary Policy and Financial Stability At the 2014 Michel Camdessus Central Banking Lecture, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C. July 2, 2014

It is an honor to deliver the inaugural Michel Camdessus Central Banking Lecture. Michel Camdessus served with distinction as governor of the Banque de France and was one of the longest-serving managing directors of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In these roles, he was well aware of the challenges central banks face in their pursuit of price stability and full employment, and of the interconnections between macroeconomic stability and financial stability. Those interconnections were apparent in the Latin American debt crisis, the Mexican peso crisis, and the East Asian financial crisis, to which the IMF responded under Camdessus’s leadership. These episodes took place in emerging market economies, but since then, the global financial crisis and, more recently, the euro crisis have reminded us that no economy is immune from financial instability and the adverse effects on employment, economic activity, and price stability that financial crises cause. The recent crises have appropriately increased the focus on financial stability at central banks around the world. At the Federal Reserve, we have devoted substantially increased resources to monitoring financial stability and have refocused our regulatory and supervisory efforts to limit the buildup of systemic risk. There have also been calls, from some quarters, for a fundamental reconsideration of the goals and strategy of monetary policy. Today I will focus on a key question spurred by this debate: How should monetary and other policymakers balance macroprudential approaches and monetary policy in the pursuit of financial stability? In my remarks, I will argue that monetary policy faces significant limitations as a tool to promote financial stability: Its effects on financial vulnerabilities, such as excessive leverage and maturity transformation, are not well understood and are less direct than a regulatory or supervisory approach; in addition, efforts to promote financial stability through adjustments in interest rates would increase the volatility of inflation and employment. As a result, I believe a macroprudential approach to supervision and regulation needs to play the primary role. Such an approach should focus on “through the cycle” standards that increase the resilience of the financial system to adverse shocks and on efforts to ensure that the regulatory umbrella will cover previously uncovered systemically important institutions and activities. These efforts should be complemented by the use of countercyclical macroprudential tools, a few of which I will describe. But experience with such tools remains limited, and we have much to learn to use these measures effectively. I am also mindful of the potential for low interest rates to heighten the incentives of financial market participants to reach for yield and take on risk, and of the limits of macroprudential measures to address these and other financial stability concerns. Accordingly, there may be times when an adjustment in monetary policy may be appropriate to ameliorate emerging risks to financial stability. Because of this possibility, and because transparency enhances the effectiveness of monetary policy, it is crucial that policymakers communicate their views clearly on the risks to financial stability and how such risks influence the appropriate monetary policy stance. I will conclude by briefly laying out how financial stability concerns affect my current assessment of the appropriate stance of monetary policy. Balancing Financial Stability with Price Stability: Lessons from the Recent Past Despite these complementarities, monetary policy has powerful effects on risk taking. Indeed, the accommodative policy stance of recent years has supported the recovery, in part, by providing increased incentives for households and businesses to take on the risk of potentially productive investments. But such risk-taking can go too far, thereby contributing to fragility in the financial system.1 This possibility does not obviate the need for monetary policy to focus primarily on price stability and full employment–the costs to society in terms of deviations from price stability and full employment that would arise would likely be significant. I will highlight these potential costs and the clear need for a macroprudential policy approach by looking back at the vulnerabilities in the U.S. economy before the crisis. I will also discuss how these vulnerabilities might have been affected had the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy in the mid-2000s to promote financial stability. Looking Back at the Mid-2000s In the private sector, key vulnerabilities included high levels of leverage, excessive dependence on unstable short-term funding, weak underwriting of loans, deficiencies in risk measurement and risk management, and the use of exotic financial instruments that redistributed risk in nontransparent ways. In the public sector, vulnerabilities included gaps in the regulatory structure that allowed some systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) and markets to escape comprehensive supervision, failures of supervisors to effectively use their existing powers, and insufficient attention to threats to the stability of the system as a whole. It is not uncommon to hear it suggested that the crisis could have been prevented or significantly mitigated by substantially tighter monetary policy in the mid-2000s. At the very least, however, such an approach would have been insufficient to address the full range of critical vulnerabilities I have just described. A tighter monetary policy would not have closed the gaps in the regulatory structure that allowed some SIFIs and markets to escape comprehensive supervision; a tighter monetary policy would not have shifted supervisory attention to a macroprudential perspective; and a tighter monetary policy would not have increased the transparency of exotic financial instruments or ameliorated deficiencies in risk measurement and risk management within the private sector. Some advocates of the view that a substantially tighter monetary policy may have helped prevent the crisis might acknowledge these points, but they might also argue that a tighter monetary policy could have limited the rise in house prices, the use of leverage within the private sector, and the excessive reliance on short-term funding, and that each of these channels would have contained–or perhaps even prevented–the worst effects of the crisis. A review of the empirical evidence suggests that the level of interest rates does influence house prices, leverage, and maturity transformation, but it is also clear that a tighter monetary policy would have been a very blunt tool: Substantially mitigating the emerging financial vulnerabilities through higher interest rates would have had sizable adverse effects in terms of higher unemployment. In particular, a range of studies conclude that tighter monetary policy during the mid-2000s might have contributed to a slower rate of house price appreciation. But the magnitude of this effect would likely have been modest relative to the substantial momentum in these prices over the period; hence, a very significant tightening, with large increases in unemployment, would have been necessary to halt the housing bubble.2 Such a slowing in the housing market might have constrained the rise in household leverage, as mortgage debt growth would have been slower. But the job losses and higher interest payments associated with higher interest rates would have directly weakened households’ ability to repay previous debts, suggesting that a sizable tightening may have mitigated vulnerabilities in household balance sheets only modestly.3 Similar mixed results would have been likely with regard to the effects of tighter monetary policy on leverage and reliance on short-term financing within the financial sector. In particular, the evidence that low interest rates contribute to increased leverage and reliance on short-term funding points toward some ability of higher interest rates to lessen these vulnerabilities, but that evidence is typically consistent with a sizable range of quantitative effects or alternative views regarding the causal channels at work.4 Furthermore, vulnerabilities from excessive leverage and reliance on short-term funding in the financial sector grew rapidly through the middle of 2007, well after monetary policy had already tightened significantly relative to the accommodative policy stance of 2003 and early 2004. In my assessment, macroprudential policies, such as regulatory limits on leverage and short-term funding, as well as stronger underwriting standards, represent far more direct and likely more effective methods to address these vulnerabilities.5 Recent International Experience For example, Canada, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom have expressed a willingness to use monetary policy to address financial stability concerns in unusual circumstances, but they have similarly concluded that macroprudential policies should serve as the primary tool to pursue financial stability. In Canada, with inflation below target and output growth quite subdued, the Bank of Canada has kept the policy rate at or below 1 percent, but limits on mortgage lending were tightened in each of the years from 2009 through 2012, including changes in loan-to-value and debt-to-income caps, among other measures.7 In contrast, in Norway and Sweden, monetary policy decisions have been influenced somewhat by financial stability concerns, but the steps taken have been limited. In Norway, policymakers increased the policy interest rate in mid-2010 when they were facing escalating household debt despite inflation below target and output below capacity, in part as a way of “guarding against the risk of future imbalances.”8 Similarly, Sweden’s Riksbank held its policy rate “slightly higher than we would have done otherwise” because of financial stability concerns.9 In both cases, macroprudential actions were also either taken or under consideration. In reviewing these experiences, it seems clear that monetary policymakers have perceived significant hurdles to using sizable adjustments in monetary policy to contain financial stability risks. Some proponents of a larger monetary policy response to financial stability concerns might argue that these perceived hurdles have been overblown and that financial stability concerns should be elevated significantly in monetary policy discussions. A more balanced assessment, in my view, would be that increased focus on financial stability risks is appropriate in monetary policy discussions, but the potential cost, in terms of diminished macroeconomic performance, is likely to be too great to give financial stability risks a central role in monetary policy decisions, at least most of the time. If monetary policy is not to play a central role in addressing financial stability issues, this task must rely on macroprudential policies. In this regard, I would note that here, too, policymakers abroad have made important strides, and not just those in the advanced economies. Emerging market economies have in many ways been leaders in applying macroprudential policy tools, employing in recent years a variety of restrictions on real estate lending or other activities that were perceived to create vulnerabilities.10 Although it is probably too soon to draw clear conclusions, these experiences will help inform our understanding of these policies and their efficacy. Promoting Financial Stability through a Macroprudential Approach In weighing these questions, I find it helpful to distinguish between tools that primarily build through-the-cycle resilience against adverse financial developments and those primarily intended to lean against financial excesses.12 Building Resilience In the United States, considerable progress has been made on each of these fronts. Changes in bank capital regulations, which will include a surcharge for systemically important institutions, have significantly increased requirements for loss-absorbing capital at the largest banking firms. The Federal Reserve’s stress tests and Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review process require that large financial institutions maintain sufficient capital to weather severe shocks, and that they demonstrate that their internal capital planning processes are effective, while providing perspective on the loss-absorbing capacity across a large swath of the financial system. The Basel III framework also includes liquidity requirements designed to mitigate excessive reliance by global banks on short-term wholesale funding. Oversight of the U.S. shadow banking system also has been strengthened. The new Financial Stability Oversight Council has designated some nonbank financial firms as systemically important institutions that are subject to consolidated supervision by the Federal Reserve. In addition, measures are being undertaken to address some of the potential sources of instability in short-term wholesale funding markets, including reforms to the triparty repo market and money market mutual funds–although progress in these areas has, at times, been frustratingly slow. Additional measures should be taken to address residual risks in the short-term wholesale funding markets. Some of these measures–such as requiring firms to hold larger amounts of capital, stable funding, or highly liquid assets based on use of short-term wholesale funding–would likely apply only to the largest, most complex organizations. Other measures–such as minimum margin requirements for repurchase agreements and other securities financing transactions–could, at least in principle, apply on a marketwide basis. To the extent that minimum margin requirements lead to more conservative margin levels during normal and exuberant times, they could help avoid potentially destabilizing procyclical margin increases in short-term wholesale funding markets during times of stress. Leaning Against the Wind Nonetheless, some macroprudential tools can be adjusted in a manner that may further enhance resilience as risks emerge. In addition, macroprudential tools can, in some cases, be targeted at areas of concern. For example, the new Basel III regulatory capital framework includes a countercyclical capital buffer, which may help build additional loss-absorbing capacity within the financial sector during periods of rapid credit creation while also leaning against emerging excesses. The stress tests include a scenario design process in which the macroeconomic stresses in the scenario become more severe during buoyant economic expansions and incorporate the possibility of highlighting salient risk scenarios, both of which may contribute to increasing resilience during periods in which risks are rising.13 Similarly, minimum margin requirements for securities financing transactions could potentially vary on a countercyclical basis so that they are higher in normal times than in times of stress. Implications for Monetary Policy, Now and in the Future First, it is critical for regulators to complete their efforts at implementing a macroprudential approach to enhance resilience within the financial system, which will minimize the likelihood that monetary policy will need to focus on financial stability issues rather than on price stability and full employment. Key steps along this path include completion of the transition to full implementation of Basel III, including new liquidity requirements; enhanced prudential standards for systemically important firms, including risk-based capital requirements, a leverage ratio, and tighter prudential buffers for firms heavily reliant on short-term wholesale funding; expansion of the regulatory umbrella to incorporate all systemically important firms; the institution of an effective, cross-border resolution regime for systemically important financial institutions; and consideration of regulations, such as minimum margin requirements for securities financing transactions, to limit leverage in sectors beyond the banking sector and SIFIs. Second, policymakers must carefully monitor evolving risks to the financial system and be realistic about the ability of macroprudential tools to influence these developments. The limitations of macroprudential policies reflect the potential for risks to emerge outside sectors subject to regulation, the potential for supervision and regulation to miss emerging risks, the uncertain efficacy of new macroprudential tools such as a countercyclical capital buffer, and the potential for such policy steps to be delayed or to lack public support.14 Given such limitations, adjustments in monetary policy may, at times, be needed to curb risks to financial stability.15 These first two principles will be more effective in helping to address financial stability risks when the public understands how monetary policymakers are weighing such risks in the setting of monetary policy. Because these issues are both new and complex, there is no simple rule that can prescribe, even in a general sense, how monetary policy should adjust in response to shifts in the outlook for financial stability. As a result, policymakers should clearly and consistently communicate their views on the stability of the financial system and how those views are influencing the stance of monetary policy. To that end, I will briefly lay out my current assessment of financial stability risks and their relevance, at this time, to the stance of monetary policy in the United States. In recent years, accommodative monetary policy has contributed to low interest rates, a flat yield curve, improved financial conditions more broadly, and a stronger labor market. These effects have contributed to balance sheet repair among households, improved financial conditions among businesses, and hence a strengthening in the health of the financial sector. Moreover, the improvements in household and business balance sheets have been accompanied by the increased safety of the financial sector associated with the macroprudential efforts I have outlined. Overall, nonfinancial credit growth remains moderate, while leverage in the financial system, on balance, is much reduced. Reliance on short-term wholesale funding is also significantly lower than immediately before the crisis, although important structural vulnerabilities remain in short-term funding markets. Taking all of these factors into consideration, I do not presently see a need for monetary policy to deviate from a primary focus on attaining price stability and maximum employment, in order to address financial stability concerns. That said, I do see pockets of increased risk-taking across the financial system, and an acceleration or broadening of these concerns could necessitate a more robust macroprudential approach. For example, corporate bond spreads, as well as indicators of expected volatility in some asset markets, have fallen to low levels, suggesting that some investors may underappreciate the potential for losses and volatility going forward. In addition, terms and conditions in the leveraged-loan market, which provides credit to lower-rated companies, have eased significantly, reportedly as a result of a “reach for yield” in the face of persistently low interest rates. The Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation issued guidance regarding leveraged lending practices in early 2013 and followed up on this guidance late last year. To date, we do not see a systemic threat from leveraged lending, since broad measures of credit outstanding do not suggest that nonfinancial borrowers, in the aggregate, are taking on excessive debt and the improved capital and liquidity positions at lending institutions should ensure resilience against potential losses due to their exposures. But we are mindful of the possibility that credit provision could accelerate, borrower losses could rise unexpectedly sharply, and that leverage and liquidity in the financial system could deteriorate. It is therefore important that we monitor the degree to which the macroprudential steps we have taken have built sufficient resilience, and that we consider the deployment of other tools, including adjustments to the stance of monetary policy, as conditions change in potentially unexpected ways. Conclusion

Other Formats 80 KB PDF1. The possibility that periods of relative economic stability may contribute to risk-taking and the buildup of imbalances that may unwind in a painful manner is often linked to the ideas of Hyman Minsky (see Hyman P. Minsky (1992), “The Financial Instability Hypothesis (PDF),” 2. For a discussion of this issue encompassing experience across a broad range of advanced economies in the 2000s, including the United States, see Jane Dokko, Brian M. Doyle, Michael T. Kiley, Jinill Kim, Shane Sherlund, Jae Sim, and Skander Van Den Heuvel (2011), “Monetary Policy and the Global Housing Bubble,” 3. The notion that tighter monetary policy may have ambiguous effects on leverage or repayment capacity is illustrated in, for example, Anton Korinek and Alp Simsek (2014), “Liquidity Trap and Excessive Leverage (PDF),” 4. See, for example, Tobias Adrian and Hyun Song Shin (2010), “Liquidity and Leverage,” 5. This evidence and experience suggest that a reliance on monetary policy as a primary tool to address the broad range of vulnerabilities that emerged in the mid-2000s would have had uncertain and limited effects on risks to financial stability. Such uncertainty does not imply that a modestly tighter monetary policy may not have been marginally helpful. For example, some research suggests that financial imbalances that became apparent in the mid-2000s may have signaled a tighter labor market and more inflationary pressure than would have been perceived solely from labor market conditions and overall economic activity. Hence, such financial imbalances may have called for a modestly tighter monetary policy through the traditional policy lens focused on inflationary pressure and economic slack. See, for example, David M. Arseneau and Michael Kiley (2014), “The Role of Financial Imbalances in Assessing the State of the Economy,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, April 18). Return to text 6. For a summary of house price developments across a range of countries through 2013, see International Monetary Fund (2014), “Global Housing Watch.” 7. For a discussion of macroprudential steps taken in Canada, see Ivo Krznar and James Morsink (2014), “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility: Macroprudential Tools at Work in Canada,” 8. See Norges Bank (2010), “The Executive Board’s Monetary Policy Decision–Background and General Assessment,” 9. See Per Jansson (2013), “How Do We Stop the Trend in Household Debt? Work on Several Fronts,” 10. For a discussion, see Min Zhu (2014), “Era of Benign Neglect of House Price Booms Is Over,” 11. These questions have been explored in, for example, International Monetary Fund (2013), The Interaction of Monetary and Macroprudential Policies (PDF) 12. The IMF recently discussed tools to build resilience and lean against excesses (and provided a broad overview of macroprudential tools and their interaction with other policies, including monetary policy); see International Monetary Fund (2013), Key Aspects of Macroprudential Policy (PDF) 13. See the Policy Statement on the Scenario Design Framework for Stress Testing at Regulation YY–Enhanced Prudential Standards and Early Remediation Requirements for Covered Companies (PDF), 12 C.F.R. pt. 252 (2013), Policy Statement on the Scenario Design Framework for Stress Testing. Return to text 14. For a related discussion, see Elliott, Feldberg, and Lehnert, “The History of Cyclical Macroprudential Policy in the United States.” Return to text 15. Adam and Woodford (2013) present a model in which macroprudential policies are not present and housing prices experience swings for reasons not driven by “fundamentals.” In this context, adjustments in monetary policy in response to house price booms–even if such adjustments lead to undesirable inflation or employment outcomes–are a component of optimal monetary policy. See Klaus Adam and Michael Woodford (2013), “Housing Prices and Robustly Optimal Monetary Policy (PDF),” |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment