The Big Picture |

- Hitchcock’s Cameos. All of them.

- Lefsetz: Digital Presence

- Why Long-Term Investors Beat Short-Term Traders

- MiB: Jim Chanos, Kynikos Associates

- 10 Weekend Reads

- Mauldin: Bubbles, Bubbles Everywhere

| Hitchcock’s Cameos. All of them. Posted: 16 Aug 2014 05:00 PM PDT From each of the following: The Lodger (1927), Easy Virtue (1928), Blackmail (1929), Murder! (1930), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), Sabotage (1936), Young and Innocent (1937), The Lady Vanishes (1938), Rebecca (1940), Foreign Correspondent (1940), Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941), Suspicion (1941), Saboteur (1942), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Lifeboat (1944), Spellbound (1945), Notorious (1946), The Paradine Case (1947), Rope (1948), Under Capricorn (1949), Stage Fright (1950), Strangers on a Train (1951), I Confess (1953), Dial M for Murder (1954), Rear Window (1954), To Catch A Thief (1955), The Trouble With Harry (1955), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), The Wrong Man (1956), Vertigo (1958), North By Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960), The Birds (1963), Marnie (1964), Torn Curtain (1966), Topaz (1969), Frenzy (1972), Family Plot (1976).

Hat tip Dangerous Minds

|

| Posted: 16 Aug 2014 02:00 PM PDT 1. DIGITAL HOME A. Wikipedia Your goal is to be big enough to have a Wikipedia page. It’s the first place newbies go to learn about you. It’s got the imprimatur of authority, people believe what they read, however inaccurate the details may be. We live in an information age and what we want most is information. Where the act was formed, how you got your name, who the band members are and your discography, including chart placements. It’s best if there’s personal information, who you’re dating, who you’re married to. People want to know you. However, beware of filling out your page by yourself. One can tell when pages are written by those whose pages they are. They go on just a bit too long, there’s too much detail, whereas fans have a different tone, somewhat reverential and completist in a different fashion. After you read someone’s Wikipedia page you should still want more. B. Website/Facebook page/Bandcamp page, etc. If you don’t have a Wikipedia page, because you haven’t got enough traction, buy your name and establish a page at that URL. It’s got so much more gravitas than a Facebook page. You want to let people know you’re for real, that you invested some money, that you’re in it for the long haul, anybody can have a Facebook page, it tends not to be taken seriously. Of course, if you’re big enough to have a Wikipedia page, you need your own website and a Facebook page. Once again, on your website, you need to provide information. Like tour dates. And lyrics. And it’s best if there’s a constant flow of information, so people will come back. And don’t put up a paywall, if people believe they can’t get it all for free, they’re not going to become enamored of you. 2. YOUTUBE America’s radio station and record store all rolled up into one. All your cuts should be up there. Don’t have any fan clips taken down. Just monetize those that appear. The smaller the act, the more important it is to post videos on a regular basis. Of covers. Maybe even of you talking to your audience. But if you’re talking, make it brief, you’re a musician not an orator and if you go on too long chances are people will get bored, or wonder who these clips are made for. 3. SPOTIFY Don’t bitch about payments, put your music up. All of it. And you might as well put it up on the rest of the services, like Rdio, Deezer and Beats, but know that only one will triumph in the long run, it’s the way of the web, there’s only one Google, one Amazon and one Facebook. People gravitate to where everybody else is. Spotify does not have to win, but one streaming service will. 4. SOUNDCLOUD Gets more ink/press/talk than it deserves, but it is true that the younger generation goes there. Put your stuff up. But know to cover the above bases first. 5. iTUNES AND AMAZON Buying is so aughts. The teens are not about ownership but access. Sure, make your stuff available for purchase, but that’s not where the money is, certainly not in the future. Sure, being number one delivers some bragging rights, but it means less than ever before. Today it’s about fanbase and money. Don’t get caught up in charts. Don’t get caught up in smoke and mirrors. So much of what you see hyped gets no traction, never mind not making any money. That’s a fool’s errand, playing the popularity game. If you make it, your fans will make you more popular, they will spread the word, continuously, which news sites never will. News sites are all about the new. They’re voracious predators that will squeeze you dry one day and forget about you the next. Use news to make a splash, but it’s meaningless unless fans become aware of you, embrace you and tell everybody else about you. 6. SOCIAL MEDIA People want to interact with you, but don’t get caught up in believing the social media game is either necessary or important. The bottom line is social media is mostly about making the hoi polloi, consumers, fans, feel important. They’re the ones that are posting and looking for attention. You want to give them enough info so they’ll post about you, but your personal Twitter account doesn’t mean much unless you’re a worldwide superstar, and so often that doesn’t mean much, because those people don’t have time to post themselves. So you want a Facebook page. Don’t feel pressured to post on it yourself, let your minions do so. And you want a Twitter account. It’s great if you post, but Twitter can be a huge time-sucker that pays few dividends. Better to practice your instrument than to live on Twitter. 7. GOSSIP Paris Hilton established the paradigm, Kim Kardashian perfected it. Gossip is a career unto itself, which is why so many of its practitioners are famous for nothing else. So beware of the gossip columns unless that’s your primary game, they make musicians look small, which is why Kanye is faltering. 8. NEWS SITES Press releases are irrelevant unless you’re truly a star and your tour is canceled or you kicked out a band member or you signed a movie deal. However, for the past couple of years, it’s better if you share this info yourself on one of your own sites. It makes the bond to your fans so much clearer. 9. PERIPHERAL SITES Just because it’s available that does not mean anybody will see it. Sure, stream your album on NPR, if it’s available absolutely everywhere else, otherwise it looks like you’re playing in a walled garden, one where most people are unaware of you. It comes down to Google. When I Google your name, what comes up? Hopefully your personal website and then your Wikipedia page, or vice versa. Right now there’s nowhere to go where all of your online presence is listed, which is why the major sites are so important. Sure, some fans might get past the first page of Google, but most don’t get past the first two HITS! Everything I want to know about you should come up there. If not, your team is not doing it right. 10. FADS The longer we live in the Internet age, the more things stay the same. It comes down to the art. The music and then the video. And there’s so much information, that it helps to have money to make an initial impression, to get the ball rolling. And then it’s about being available absolutely everywhere so if someone’s interested in you, they can experience you. Don’t overthink it. Don’t release a single from your album every week. We’re on information overload, we can’t keep paying attention, the only ones who do are the hardest core of fans. Beyonce had it right. Announce and release simultaneously, all of it. Because the truth is very little lasts. So you want the benefit of the splash. You want to sell while you’re promoting. And if you’re lucky, you’ll get traction. Market manipulation is history. You do it in an obvious way. And you make your fans happy. They are the ones who will grow you, it’s very hard to get someone who’s not concerned to be so. So much is hyped every day that people don’t have time to click through and check you out. The plethora of information might get them to your Wikipedia page, to YouTube, which is why you must have a presence there, but the truth is the power lays in the hands of those you’ve already converted, they will not stop talking about you, they will implore others to check you out. Which is why it’s so important to focus. When someone spreads the word, make sure one track stands above. That’s one great thing about Spotify, they list the tracks in order of popularity. Always put yourself in the shoes of the know-nothings. If they get bitten, how can they enter your universe? Make it complicated, require multiple clicks, more Googling, and they won’t make the effort. Meanwhile, keep feeding your fans. You’ve got two trains running, making those already converted happy and entrancing new people, and don’t confuse the two. Don’t wait so long to put out new material that the hard core fan is frustrated and moves on. And don’t think that the newbie is interested in anything more than the single. But if someone is interested, they should be able to go online and go down the rabbit hole into your career. They should be able to spend hours researching, learning and listening. And you’ve got to make it easy for them to do this, by not only being everywhere, but pointing to what they should devour first. You don’t take someone to their first French restaurant and insist that they eat the snails. Start out with the killer onion soup, then maybe the duck. If they like that they’ll sample the foie gras and keep talking about you. Then again, food’s got a whole network devoted to it, where the personalities shine but the food trumps and triumphs. So many in music have lost the plot. Not only does MTV not focus on music, so many musicians are focused on their brand, their stardom and sponsorships. Put the music front and center. If you hew to this mantra the rest will follow.

~~~ – |

| Why Long-Term Investors Beat Short-Term Traders Posted: 16 Aug 2014 08:30 AM PDT No matter what, the long-term investor comes out ahead of the short-term trader

Last time, we looked at why traders are at an almost insurmountable disadvantage against investors due to short-term capital gains taxes. Many of you wrote in to note several factors that would have allowed the active trader to narrow the gap against the long-term investor. A few of you asked how likely it was that a trader would outperform by that margin year after year. This week, I want to review those issues readers raised, looking to see how they affected our competition between the long-term indexer and the short-term trader. Spoiler alert: The issues to which I gave short shrift did improve the performance of the trader, but not nearly enough to narrow the gap between the two. Let's look at the details. There are three factors I oversimplified or overlooked: The first is the tax loss carry forward. This was the biggest issue raised by readers and the one that had the single biggest impact on the net performance of the trader's account. As readers noted, the IRS allows losses from past years to be carried forward, reducing the tax bite in outlying years following a big down year such as 2008 or '09. This will narrow the gap between our two competitors. For the two to see similar performance net of taxes, the trader need only outperform the benchmark index by about 30 percent instead of the 40 percent we discussed. A challenging bogey to be sure, but less so than I originally stated. Second, several people raised the issue of dividends working for the investor but not for the trader. I elected to ignore them for traders in my comparison and ended up understating the trader's performance ever so slightly. An account that is trading equities actively, with relatively short holding periods, may or may not be a holder of record when a dividend is issued in any given quarter. And when a stock goes ex-dividend, its share price typically drops by the amount of the dividend, making it a wash to shorter-term traders. Some readers who trade actively noted that they had healthy dividend incomes each year and had the tax filings to prove it. However, the amounts involved relative to the investor were minor. Consider that an investor who held on to the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index for the year of 2013 captured a dividend yield of a little over 2 percent. I assumed traders missed at least half of that, as they were buying and selling stocks. They then paid taxes on what they did collect. We are left with a likely gain of plus or minus 1 percent, and I suspect for many active traders, it's closer to zero than 1 percent. I discounted the dividend to traders entirely, as it's not especially significant to the total performance. I am going to stay with that call. The third factor several of you pointed out, which is significant, was that the long-term investor still owed taxes on their gains. Assuming the portfolio was not in an IRA or 401(k) or other tax-advantaged structure, long-term capital gains are owed. Our passive index investor is likely to owe a 20 percent capital gains tax when cashing out. Keep in mind, however, that this investor typically draws down 4.5 percent per year in retirement. Their tax bite is going to be at its lowest level in their lifetime during retirement. Given modern life spans, they can also expect to benefit from continuing appreciation of their passive portfolios during their 20-plus years of retirement. These taxes will narrow that gap, but it is offset by potential gains over the retirement period. The extent of the offset depends on how much the market gains over that 20-year period. Active traders do not garner that benefit (unless they roll their trading accounts over into a broad index). Note that I assume none of you plan to spend your golden years watching the market tick by tick and jumping in and out of stocks. In our theoretical competition, if the issues raised by readers are resolved in the trader's favor, the gap between the two is narrowed. Losses carried forward reduce the disadvantage to the trader, dividends help ever so slightly and taxes owed by the investor reduce his net gains. Let's assume that all ties go to the runner: If we were to be aggressive in our assumptions favoring the trader, all the benefits of those issues raised by readers to the active portfolio reduce the outperformance by the indexer. But it is still substantial, as the active trader "only" has to outperform the S&P 500 by 25 percent instead of 40 percent. Those were the issues raised by traders who challenged my underlying premise. Readers who were sympathetic to my argument raised different but just as important questions. Three issues from the investor side were: 1. How likely was it that any trader was going to beat the market in any given year? 2. By how much was that trader likely to beat the market? 3. What are the odds the trader would beat the market 20-plus years in a row? These questions get to the heart of the active vs. passive debate. The data is terribly unfavorable to the active trader by an immense margin. Indeed, the math of active management is daunting. Let's use mutual fund performance as our stand-in for active traders. Data from Morningstar and Vanguard shows that in any given year, 20 to 30 percent of active managers can outperform their benchmarks. Note that this is usually by a few percent, and not the 25 percent we have discussed. But that's for only one year. Where things get interesting is what happens when we look at consecutive years. For any manager who outperforms in a given year, only 1 in 10 will continue to outperform in two of the next three years. In other words, 10 percent of our original outperformers — about 3 percent total — can keep their streak alive for three consecutive years. Over five years, only 1 in 33 of our original alpha generators keeps the winning streak going. Once we figure in their costs and fees, it works out to be less than 1 percent — 1 in 100 — who manage a net outperformance of a few basis points a year. Perhaps the best-known winning streak of all time has been that by Legg Mason's Bill Miller. Over 15 years (1991-2005) his Capital Management Value Trust (LMVTX) outperformed the S&P 500. Note that this period included two Middle East wars, the dot-com crash and the housing boom. Miller, a deep-value manager, saw his streak end when the housing boom busted and the credit crisis crushed the financial sector (LMVTX had concentrated exposure to that sector). The fund went from the top 1 percent of all mutual funds to the bottom 1 percent over the ensuing years. Hence, our thought experiment requires us to begin with what has proved to be an impossibility: beating the market by a substantial percentage for an unprecedented number of years. I may have somewhat overstated some of the tax disadvantages of the active trader vs. the passive indexer. But the bottom line remains the same: Short-term taxes that are paid — and therefore not compounded over the decades — take a huge bite out of a portfolio. That assumes you are a terrific trader. But the odds are that you are not. Forget alpha, or market beating returns. Most people don't even achieve beta, which is market matching returns. In the real world, the win goes to the passive indexer. ~~~ Ritholtz is chief investment officer of Ritholtz Wealth Management. He is the author of "Bailout Nation" and runs a finance blog, the Big Picture. Twitter: @Ritholtz. |

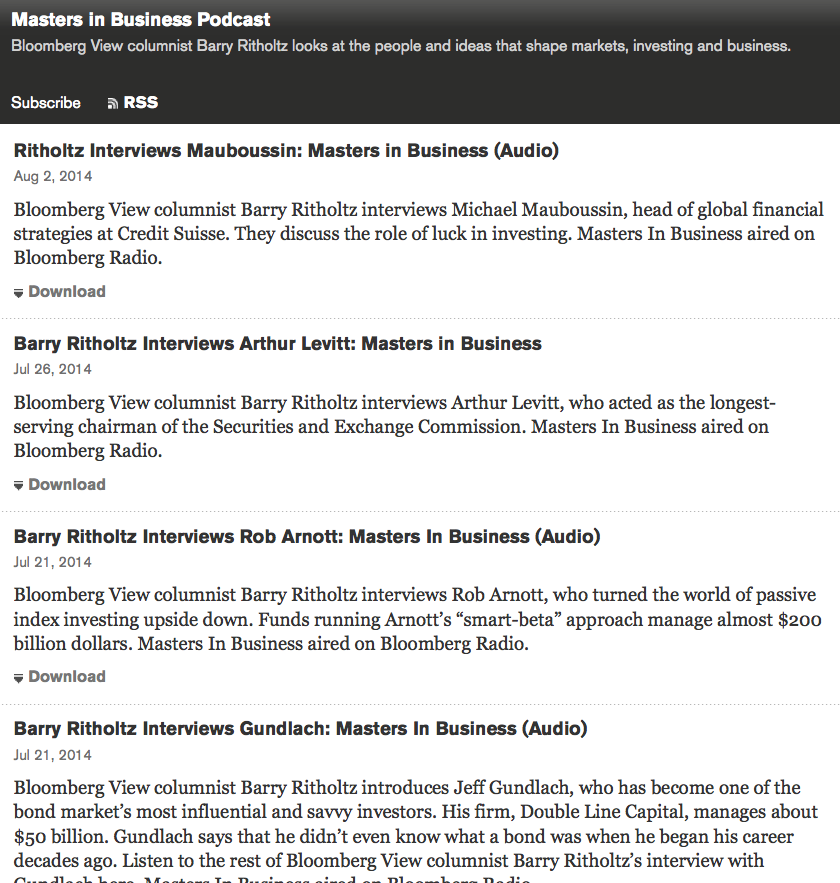

| MiB: Jim Chanos, Kynikos Associates Posted: 16 Aug 2014 06:45 AM PDT This week’s Masters in Business Radio show is on at 10:00 am and 6:00 pm on Bloomberg Radio 1130AM and Siriux XM 119. Our guest is famed short seller and hedge fund manager Jim Chanos. You can listen to live here. All of the past Podcasts are here and at Soundcloud and coming soon to Apple iTunes.

|

| Posted: 16 Aug 2014 04:30 AM PDT Happy weekend! Settle into your favorite easy chair, pour yourself some coffee, and enJoy our long form reads:

What’s up for the weekend?

Banks, Financial Firms Load Up On Cheap Debt

|

| Mauldin: Bubbles, Bubbles Everywhere Posted: 16 Aug 2014 03:00 AM PDT Bubbles, Bubbles Everywhere

Easy Money Will Lead to Bubbles |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment