The Big Picture |

- Stephen Moore’s Ode to the American Workers His Policies Harm

- FOMC Minutes

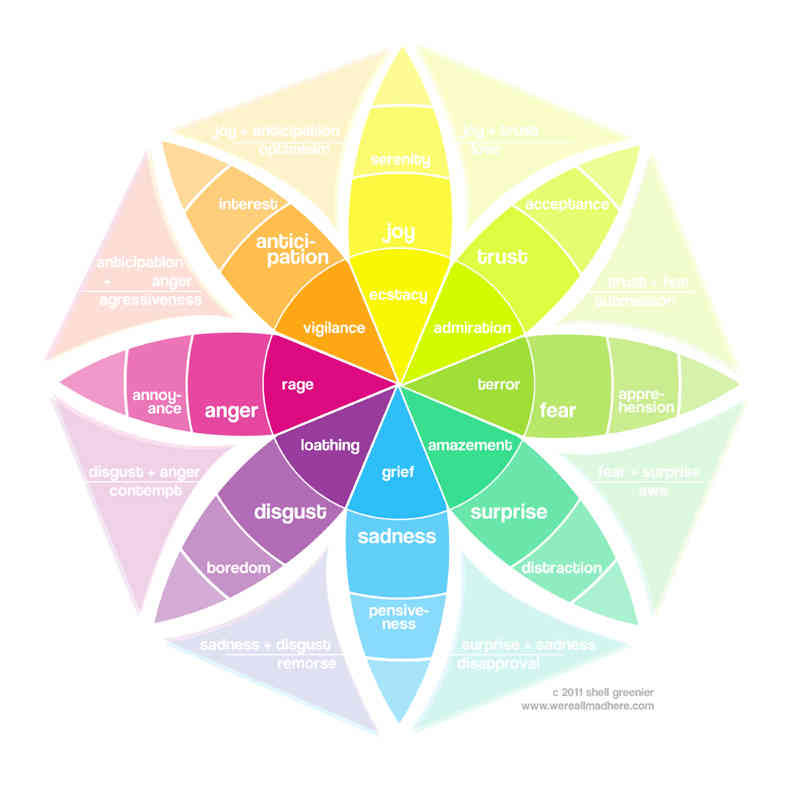

- Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions

- Oil Price Shock—Again by Phil Dodge

- Employment Chart Update

- Don’t Be a Clown With This Market

- United States Federal Tax Dollars

- When Do You Fire a Manager?

- ISM services soften a bit

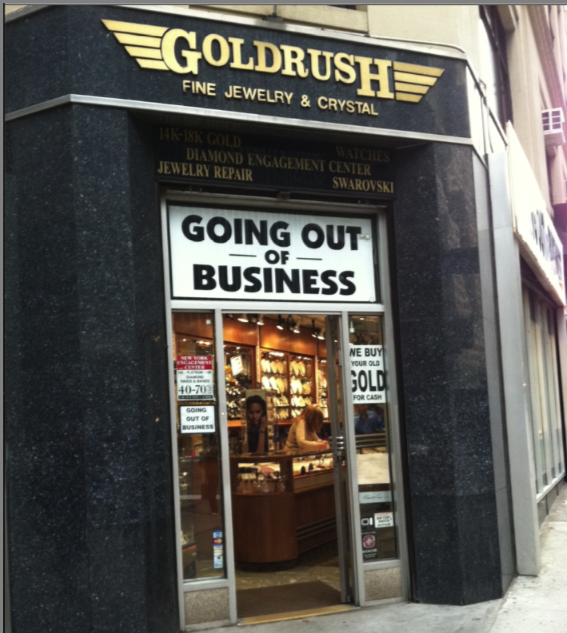

- Is the Gold Rush Over?

| Stephen Moore’s Ode to the American Workers His Policies Harm Posted: 05 Apr 2011 10:30 PM PDT Stephen Moore's ode to the American Workers his Policies Harm > My next columns address three writings by Stephen Moore, the Wall Street Journal’s "senior economics writer." White Collar Witch Hunt: Why do Republicans so easily accept Neobolshevism as a cost of doing business? [The article appeared in the American Spectator in September 2005.] “Bullish on Bush: How the Ownership Society Is Making America Richer.” [Madison Books, 2004.] We’ve Become a Nation of Takers, Not Makers. [Wall Street Journal, April 1, 2011.] Moore’s column deplores the debasement of the American economy by government employees.

The claim that employees involved in making physical things that are purchased in the markets are uniquely valorous is an odd argument for someone with his professional career (Moore ran the ultra conservative, "supply side" anti-tax group, the Club for Growth). The trade and tax policies he embraces encouraged U.S. businesses to export their manufacturing plants (and their jobs) to low-wage/low-tax nations and to import food produced in those low-wage/low-tax nations. Moore has praised both states and nations that serve as tax havens. He has singled out the Texas model – low wage, low tax, low government services, and hostile to safety rules. Moore has worked for years to punish the "makers" and produce the condition he deplores in which the number of U.S. "makers" has fallen sharply. His column decries the budgetary crises in states and localities, but it was the Great Recession driven by the criminogenic environment his anti-regulatory policies created together with the anti-tax hysteria generated by his repeatedly falsified fantasy that slashing taxes for the rich increases tax revenues that drove that budgetary crisis. Architects of the crisis like Moore who write primarily to excuse their consistent failures should stop. They have done enough damage to the world for a dozen lifetimes. Consider the implications of Moore’s assertion that people who do not work in manufacturing and farming are "takers." Under this dichotomy the world is divided between "makers" and "takers," the biggest "takers" in the world work on Wall Street, the City of London, and the worst kleptocracies – the Wall Street Journal’s core readership. If "makers" of manufactured goods and crops are uniquely valorous, then Moore’s logic requires that it is the workers in these sectors – not the managers, professionals, and clerical workers – who are the actual "makers" who embody that unique valor. (Again, it is passing strange that Moore has dedicated his life to rewarding these uniquely valorous Americans by exporting their jobs and leaving them unemployed or employed at lower wages.) If one can claim to be a "maker" by performing functions that merely assist the actual "makers" make things, then we are all "makers." Moore, however, implicitly makes two assertions about government employees – all government employees are "takers" and only government employees are "takers." Moore doesn’t attempt to support any of his assertions, and they are logically inconsistent. These truths are apparently self-evident to Mr. Moore – people are not created equal. Americans who choose to be government employees are inferior because they are not endowed by their creator with an adequate taste for risk.

In Moore’s world, an American who wishes to work as a "maker" and develops the skills to be a "maker" has no inalienable right to a job as a "maker" at a living wage. Why? If (1) there really is something particularly virtuous about working in manufacturing or farming, (2) there are too few Americans working in those industries, and (3) the Americans who wish to work in those industries embrace "tak[ing] career risks" and have prepared themselves by education to be able to be productive "makers" why not commit the U.S. to ensure that these virtuous, risk-loving young people can find jobs in manufacturing and farming in the U.S. Moore is not strong on nuance. All government employees are "bureaucrats" in his parable of "makers" and "takers." No corporations are bureaucratic. Moore’s fable is crude propaganda. Let us add some reality. Our largest group of federal employees provides national security (DoD, CIA, NSA, DHS, DOJ/FBI, VA, etc.). Many of these "bureaucrats" are living their parasitical life of ease as "takers" in Iraq and Afghanistan. (The virtuous Taliban are busy being "makers" – cultivating poppies.) I do not recommend telling our troops that they are risk-averse "takers" and bureaucrats. The exact number of federal employees engaged in national security is unknown because many employees in other agencies, e.g., NASA, actually work on national security under various degrees of deliberately misleading information. There are over a million federal military personnel. DoD, Homeland Security (DHS), and the VA have nearly a million civilian employees. The only other federal sector with very large numbers of employees is the Postal Service (around 600,000 – less than one-third the size of the federal workforce in the national security sector). The Postal Service, of course, provides a productive service – communications. Moore does not even attempt to explain why our federal troops or our federal communications workers are supposedly parasitical "takers." Moore does not even attempt to prove that Americans choose to work for the nation or their State because they fear taking risks. I took far more risks as a federal employee than as a private sector employee. Charles Keating hired private detectives twice to investigate me. He sued me for $400 million in my individual capacity. Another fraudulent CEO also sued me for millions of dollars. Speaker of the House James Wright sought to get me fired. One of the presidential appointees running my agency conducted what he claimed was an investigation of me with the hope that he would be able to get me fired or sued. Charles Keating gave a "secret file" to senior members of my agency that he purported had adverse information about me. The agency excluded me from meetings with Keating and removed our jurisdiction over Lincoln Savings. The head of my agency attacked me publicly in the press and in congressional testimony. (I returned the favor – he resigned in disgrace.) I was a mere financial regulator.

The overwhelmingly dominant sectors of state and local governmental employment are teaching, police, fire, and prison officers and staff. Each of these jobs would be shunned by those afraid to take risks. Moore views this hypothetical as his nightmare of American decline:

I have never met a college graduate (the context of this excerpt from Moore’s column) who aspires to work at DMV. I doubt that Moore has ever met one with that career goal. Moore chooses DMV as his example in order to disparage government and government employees. Moore believes that government workers are mediocre. Too scared and too incompetent to work in real jobs, government workers are parasitical "takers."

Ah, yes, the "rank and yank" system and executive and professional compensation have been a brilliant success in "private companies." Private systems have worked so brilliantly that they destroyed tens of trillions of dollars of wealth by creating a criminogenic environment in which private incentives became so perverse that they drove the epidemic of accounting control fraud that produced a massive financial crisis and the Great Recession. Moore thinks that failed private system should be our model for the public sector. Moore has been disastrously wrong about nearly every major economic policy issue of importance. He has learned nothing useful from his failures. Mr. Raines explained in response to a media question what was causing the repeated scandals at elite financial institutions:

Mr. Raines was speaking on behalf of the Business Roundtable, which picked him as its spokesperson to explain to the media why the epidemic of Enron-era accounting control frauds was occurring. (You can’t compete with unintended self-parody.) Raines knew what he was talking about – as Fannie’s CEO he employed an executive compensation system that created these perverse incentives. During the crisis, the fraudulent CEOs running the fraudulent liar’s lenders deliberately created intense, perverse incentives among their loan brokers, loan officers, appraisers, auditors, and rating agencies by creating a "Gresham’s" dynamic in which bad ethics drove good ethics out of the marketplace. They were exceptionally effective in achieving the desired results. The CEOs were consistently able to get overstated appraisals, overstated borrower income, clean opinions for financial statements that were not prepared in accordance with GAAP, and "AAA" ratings for toxic waste. CEOs can and do use compensation for good or evil. Moore’s discussion reveals more about him than about government employees. He can’t imagine employee excellence not based overwhelmingly on fear or quasi-bribery. He can’t imagine anyone wanting to be a teacher, a regulator, a soldier, a firefighter, a CDC scientist, a VA doctor, an FBI special agent, or a police officer. He can’t imagine people who voluntarily accept lower pay than they could get in the private sector because they want to protect people from harm. He can’t even imagine people who want a job in the local prison because they live in rural areas with high unemployment and the prison job is the best way to continue to live and work where they can help a sick mother. People work for the government for myriad reasons. Effective leaders, whether they are in the private or public sector, do not rely on threats or bribes to motivate their teams. They choose good people, train them, praise them, and give them constructive feedback. Effective leaders demonstrate through their actions integrity and dedication to the mission. Accomplishing that mission – teaching a child to read, closing fraudulent banks, putting out fires, arresting rapists, preventing a terrorist attack, or preventing criminals from escaping prison – becomes a matter of the best kind of pride and purpose. Government employees often work far longer hours than required for no additional compensation. This is, for example, overwhelmingly true of teachers. Why does Moore believe that human capital is so unimportant? His supposed "takers" are the leading "makers" and protectors of the "makers" he claims epitomize valor. It is teachers that help us become productive (and civilized). The police, firefighters, CDC, and the FDA safeguard lives. Does Moore find that unproductive? The literature on performance pay shows that even when it is not used deliberately by fraudulent leaders to create perverse incentives it can often disrupt work teams and make them less effective by creating divisiveness. It is as if a mother declared that certain of her children were superior to others. The effort to create performance pay is also perverse because it leads to demands for quantification of performance. Moore errs when he claims the government does not use performance pay. The "Reinventing Government" movement (championed by Vice President Gore and (then) Texas Governor Bush as well as many academics was premised on applying private sector management practices in the public sector. For example, Moore’s column complains about students’ test scores not improving. Student test scores did, infamously, improve dramatically in Houston, as did graduation rates, in response to performance pay tied to test performance and dropout rates. The Houston "miracle" led to Bush’s education program ("No child left behind"). The miracle was actually a fraud. The dropout rates were scammed by the Houston leadership and teachers simply taught to the test. The SEC and Justice Department use "objective" performance measures to determine bonuses. This increases the perverse incentive to bring cases against minor wrongdoers rather than against the most damaging frauds in which it is far more difficult and time-consuming to obtain convictions. The other bright idea of Reinventing Government was to order the bank regulators to refer to the banks they were supposed to regulate as their "customers." That too was a direct steal from private sector management. It is a destructive practice in the regulatory context. Moore claims that the private sector is always more efficient in providing services.

Yes, there are badly designed studies that make these claims, and then there is the reality of privatization. For example, some studies on prison operations find that private prisons are cheaper than public prisons. The problem is that these studies compare average costs of public imprisonment with the costs of private prisons for the lowest risk prisoners. Security drives prison expense, so these studies are meaningless. Privatization can also create perverse incentives. The most notorious example is the CEO of the private prison who bribed judges to sentence innocent juveniles to extensive imprisonment in order to increase the CEO’s compensation. The private sector can always cream skim some aspects of public services at what appears to the uninformed to be a saving. A private school that does not provide services to special needs students is not more efficient – it is simply taking advantage of a cross subsidy from the public sector. Privatization does not typically lead to "competitive bidding for government services" by "equally qualified private-sector workers." The sales of public assets are often not competitive and are not made at market prices. Privatization tends to be a giveaway, making the cronies with the strongest political connections wealthy (think Mexico). I have provided examples of why the "government services" provided under privatization of prisons and schools are often not equivalent because the private sector cream skims the lowest cost aspects of those services, which does nothing to reduce overall costs. The private parties often do not provide "equally qualified private-sector workers." In college education, for example, GAO studies have found that "for profit" schools have a terrible reputation for endemic fraud. They do not provide equally qualified staff. Private prisons often do the same. Private military contractors are more expensive than government troops and produce recurrent scandals because of their CEOs’ perverse incentives. American workers do fear the dynamic Moore has long championed. What is the American worker supposed to do if the outsourcing to the private sector is to India and the wages there are one-twentieth of the U.S. wages? That dynamic would lead to the impoverishment of tens of millions of American workers. In the regulatory world we have just run a real world experiment with applying private sector management theories to the private sector. We privatized many regulatory activities by adopting self-regulation. We used "early outs" to shrink the FDIC (losing many of our most experienced federal employees). We shrank the FDIC by more than three-quarters. The FDIC adopted "MERIT" (non) examination of banks (the "M" and "E" stood for "maximum efficiency). We brought the bank lobbyists "inside the tent" in financial rulemaking, i.e., in creating Basel II. We gave performance bonuses to senior FDIC officials for dramatically reducing FDIC employees. We preempted the State regulators and AGs seeking to protect consumers from predatory nonprime lenders. Each of these actions contributed to the abject regulatory failure. To sum it up, private sector financial employees, due to the perverse incentives their CEOs put in place and that Moore wishes to spread, were far worse than "mediocre" at hundreds of lenders. The incentives became so perverse that they produced multiple epidemics of fraud and led our most prestigious professionals to aid those frauds. The results were catastrophic. Moore wants to spread those perverse compensation systems and incentives throughout the public sector, where they are even more inappropriate and destructive. We have a catastrophe because the private sector incentives were perverse and the political leaders appointed anti-regulatory leaders to run the agencies. Moore invariably bases his solutions to the problems of the public sector on the private sector approach without examining the problems of the private sector approach or whether that approach makes sense in the public sector. Moore’s theme song is a straight steal from My Fair Lady: "Why can’t a woman be more like a man?" Real men ("makers") embrace risk and work in the private sector. If only government workers ("takers" – women and men too scared to take those risks) could be made more like the private sector employees all would be solved. In the movie, the song is satire designed to expose male prejudice. Moore doesn’t get the satire. |

| Posted: 05 Apr 2011 12:26 PM PDT The Fed’s minutes are here (calendar here). Courtesy of The Disciplined Investor, here is the side-by-side comparo with last meetings minutes: > |

| Posted: 05 Apr 2011 12:00 PM PDT Interesting: From Wikipedia:

|

| Oil Price Shock—Again by Phil Dodge Posted: 05 Apr 2011 11:00 AM PDT Oil Price Shock—Again by Phil Dodge

>

The call for energy independence has been made many times since President Nixon first set out that objective 37 years ago. Nixon was responding to the oil price shock that followed an embargo by the Arab members of OPEC in October 1973. The implicit assumption was and is that energy independence as an objective will avoid price shocks. The record shows otherwise. U.S. crude oil imports were 3.2 million barrels a day (BD) in 1973. They were 5.3 million BD in 1980, when the aftermath of the Iranian revolution triggered another price shock. Crude oil imports today are about 11.5 million BD. In the meantime, there has been major sloganeering, accompanied by minor steps to reverse the oil dependence that periodically causes price shocks. In March, President Obama put forth a goal of reducing oil imports one-third by 2025. In contrast to the goal set by Richard Nixon and his successors, Obama has made a proposal that can be achieved. A one-third decrease in 14 years is 3.8 million BD, or about 270,000 BD annually. In perspective, the annual reduction target is only 1-2% of consumption. Reaching that goal would seem readily achievable if proposals for both demand decreases and supply increases march forward together. To his credit, President Obama has avoided pitfalls in previous plans, which involved various factions going head to head with their own specific solutions. And they may continue to do so, even though the President includes something for just about everybody, e.g., accelerated oil drilling and expansion of nuclear power. The problem with the Obama goals is that they could be reached without avoiding future price shocks. Victory would still allow for about 7.7 million BD of oil imports, and less growth in U.S. production (perhaps none) in the meantime. Some consolation is offered, in that the mix in the 7.7 million BD plus-or-minus would shift from less Middle East to more Canada and other politically stable sources. However, oil does not know where it is coming from. Disruptions in the Middle East could still cause price shocks globally. The U.S. would be unavoidably affected, even if it no longer directly imported from Saudi Arabia, etc. This part of the problem has been largely ignored. Even if the U.S. becomes disconnected from oil imports, the Middle East, China, India, and Europe will not. Refiners in those consuming regions would bid up the price of crude oil around the world if there were a supply disruption anywhere. Oil independence would need to be across the board to avoid oil price shocks. In fact, there may be only two effective ways that future oil price shocks can be avoided. One would be a long shot. That would be if global crude oil producing capacity increases enough to offset supply disruptions that would lead to price shocks. Considerable effort is put into answering that question by the International Energy Agency, CERA, the U.S. Energy Information Administration, and OPEC. Here's where Tuohy Brothers Investment Research comes out on this issue. Demand will grow 1% annually between 2010 and 2015, or 4.1 million BD. Supply from projects currently underway will increase 14.5 million BD. Production from evolving or new discoveries will add 6.8 million BD. Those total increases will be partially offset by a decline of 19.0 BD in the base production level, at a rate of 5% annually. On those assumptions, surplus global oil producing capacity will shrink to 5% in 2015 from 7% in 2010. That outcome would be what can be called creeping oil price shock. Surplus capacity of only 5% would be tight. It would be a recipe for generally upward pressure on oil prices. If demand grows more than 1% annually, as it recently has done, the ability to replace disrupted supply would be minimal and the price impact intense. Pressure would be less if the annual decline rate on base production decreases from 5%, as both Chevron and ExxonMobil have recently indicated is a possibility. Growing production from Iraq under the new Technical Services Contracts could also play a positive role. An increase of 1.7 million BD by 2015 would seem reasonable. On paper, it could be more than 1.7 million BD, perhaps a lot more. Maybe because of the interaction of these variables, surplus capacity could be above 5% in 2015. Nevertheless, even the recent 7% has not been enough to avoid the 2011 price spike. Since uprisings began in Tunisia last January and then spread to other Arab countries, the price of oil has risen from $87 to more than $105. The only actual loss of crude oil has been about one million BD from Libya. Much of this shortfall has been made up for by higher production from Saudi Arabia, albeit with some compromise in quality. It has nevertheless been informative that a 1% decline in production has led to a 20% increase in price in less than three months. Obviously there is concern about more possible disruptions, a risk premium that has existed to some degree over the past few years. It is inflated by actual disruptions. The other and more manageable way that the U.S. and major consuming countries can mitigate price shocks is to make temporary use of strategic petroleum reserves. The U.S. has 727 million barrels in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR), and other OECD countries typically have 90 days. The U.S. SPR can support near-term withdrawals of up to 4.4 million BD. These reserves could be a powerful fighter against oil price shocks. In the past, the United States has made the distinction that the SPR would be used only to replace lost supplies but not to attack price spikes. This distinction appears inappropriate in two ways. First, tapping the SPR would deal effectively with price shocks if the disruptions are fairly temporary. Second, the expectation that the SPR would provide incremental supply if prices went up too much would be a powerful deterrent against the risk premium. If other OECD countries were on board, the impact would be considerably greater. We thank Phil for his guest commentary. David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer Philip Dodge is an Energy Analyst with Tuohy Brothers Investment Research in New York. He is a many decade veteran of analysis in the oil/energy sector. |

| Posted: 05 Apr 2011 09:30 AM PDT |

| Don’t Be a Clown With This Market Posted: 05 Apr 2011 09:17 AM PDT |

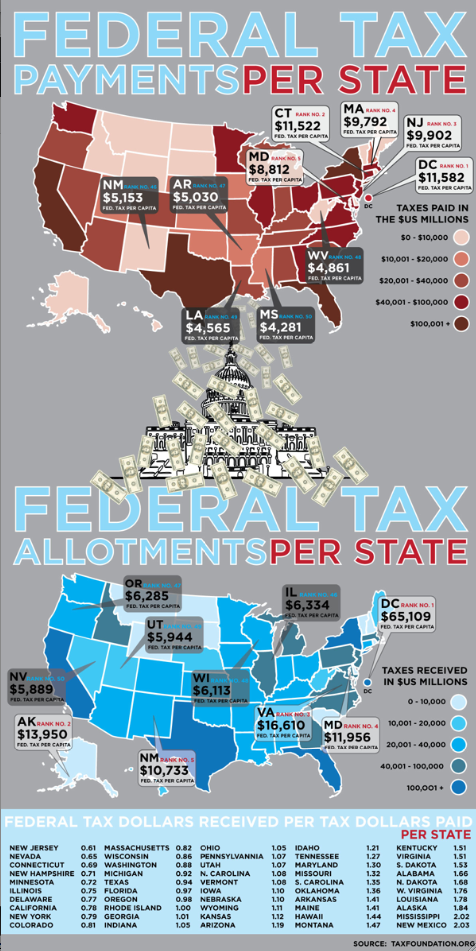

| United States Federal Tax Dollars Posted: 05 Apr 2011 08:30 AM PDT April 15th is but 10 days away, and that gives us an opportunity to post a giant tax graphic. Via Visual Economics comes this ginormous US map showing the total Federal tax dollar allotment made and received on a per state basis.The biggest states send and receive back the greatest allocation of dollars. What really matters is the per capita breakdown; you can find those in the table at the bottom of each map VE notes:

Surprising that many of the states that have the highest net tax gain are in favor of less government spending, while the states that reap the least per capita are more government spending . . . |

| Posted: 05 Apr 2011 07:00 AM PDT In one of the model portfolios we run, there are 5 best of breed mutual funds. But one of the holdings in the group, Fairholme Funds, managed by Bruce Berkowitz, has seen some recent changes. The manager became a champion of real estate developer the St. Joe Company (JOE). The fund now owns a whopping 29% of the company. Berkowitz has become a director and chairman of JOE. He is battling Greenlight Capital’s David Einhorn over the stock. Einhorn laid out his case for why he is short St. Joes (here), and believes it should be trading under $10. From an investor’s perspective, all of the above is nonsense. It appears to have been a distraction to Berkowitz, and Fairholme Funds performance has suffered. So we fired him. To be blunt, I have no interest int he outcome of this fight, These are two smart guys, and both are excellent managers. But I don’t want client’s to be the kids caught in the middle of a divorce, collateral damage of two parents arguing. Its a huge distraction, and it is not why we selected Berkowitz’s fund in the first place. It was easy to replace his value fund with the dividend SPX index (SDY), which cut the management fees to the investor by 60%. But it raises an interesting question: When do you fire your mutual fund manager? Here are my 5 criteria:

Notice that Performance is not a factor in any of the 5 bullet points above. There are two reasons for that

These are my reasons to be replace a formerly favored active manager with another vehicle. What are your reasons? |

| Posted: 05 Apr 2011 06:51 AM PDT The March ISM services index at 57.3 was 2.2 pts below expectations and down from a very high 59.7 in Feb. To put into perspective, 57 was the average in the previous expansion. Business Activity moderated to 59.7 from 66.9, the lowest since Oct. New Orders fell a touch while Backlogs rose 4 pts. Export Orders rose 2.5 pts to the best since Nov. Employment fell almost 2 pts to a 3 month low. Prices Paid fell slightly by 1.2 pts but remains high at 72.1. Of the 18 industries surveyed, 16 reported growth. Bottom line, the Japanese earthquake and rising commodity costs are the 2 main factors in the moderation, albeit at a still healthy level, as ISM specifically said “Respondents’ comments reflect concern about the recent natural disasters in Japan and the associated supply chain ramifications. Additionally, there is concern over rising costs, most notably for fuel and fuel products. Overall, most respondents remain confident about the direction of the economy.” |

| Posted: 05 Apr 2011 06:00 AM PDT |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

0 comments:

Post a Comment