The Big Picture |

- Financial Players Have “Overrun” Energy Markets

- Strawman Alert

- Tuesday LinkFest

- Gramatik Remix: Led Zep Stairway To Hip-Hop Heaven

- Not a Rally to be Proud of

- Geithner Interview on U.S. Budget

- Talking of Tomorrow

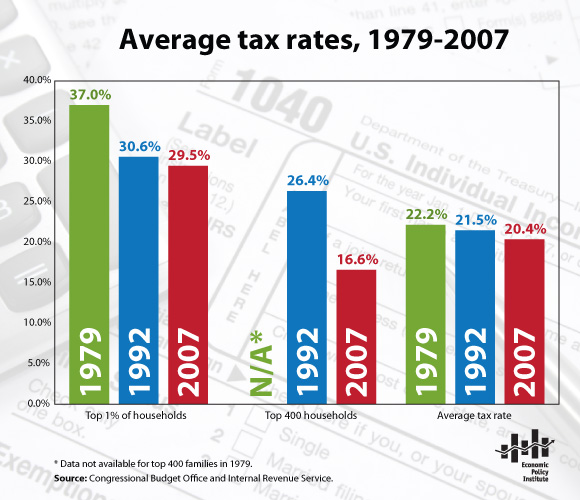

- Taxes Plunge for Rich

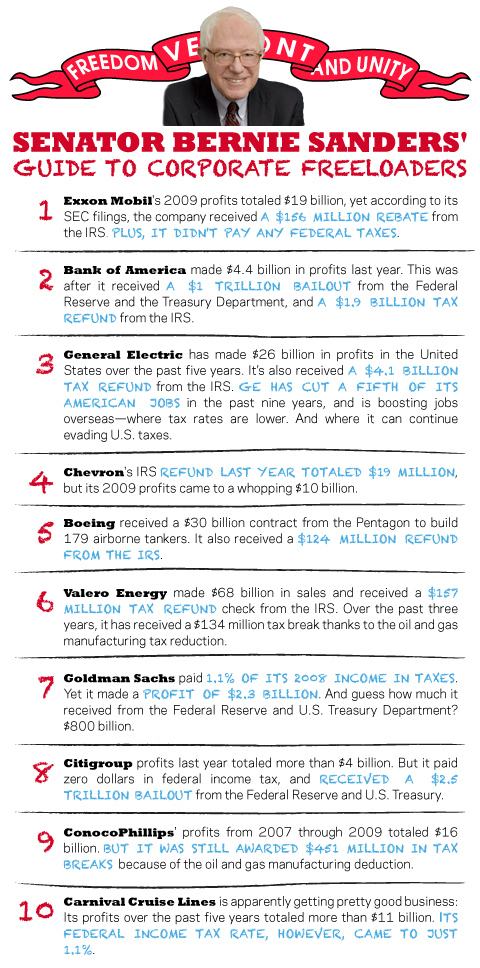

- Corporate Freeloaders

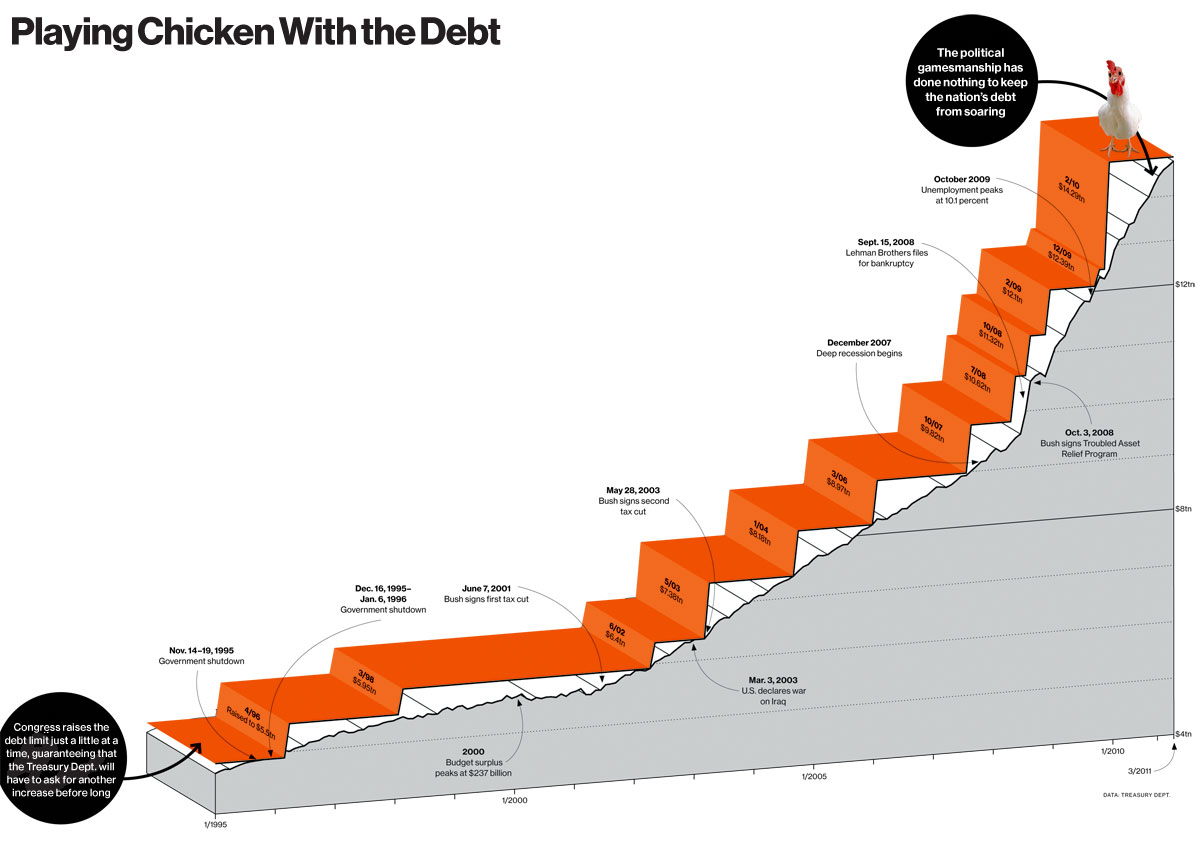

- Playing Chicken With Federal Debt Ceiling

| Financial Players Have “Overrun” Energy Markets Posted: 19 Apr 2011 11:00 PM PDT |

| Posted: 19 Apr 2011 03:30 PM PDT As the Heritage Foundation’s fingers lose their collective grip on the last rung of the ladder of credibility, William Beach, who authored their analysis of the Ryan budget proposal, takes aim at Paul Krugman, who has arguably been the biggest — but hardly the only — thorn in his side. Beach’s open letter is, regrettably, as pathetic as their recent budget analysis and subsequent hide-and-seek shenanigans with the unemployment rate. While I disagree with much of what Beach has written, I think it might be instructive to put that disagreement aside and look instead at another facet of this debate. For those who are just tuning in: Heritage’s original analysis of the Ryan budget proposal had the unemployment rate falling to a near-record-low of 2.8 percent by 2021. This, of course, raised some eyebrows. Among the first to question this projection was Krugman. We at TBP made some quick Obama/Ryan comparisons here. (Personally, I find it hard to believe that anyone from Heritage actually looked at — scrutinized — their output and questioned whether a 2.8 percent unemployment rate — without inflation, mind you — is attainable. Garbage in, garbage out, is what I’m saying. But I digress.) Within 24 hours, Heritage had disappeared the analysis that contained the 2.8 percent unemployment rate and replaced it with one that called for a higher rate. We covered that here. Some, myself included, wondered how Heritage managed to rejigger their numbers so that only the unemployment rate changed. A friend at one of the Fed’s regional banks wondered the same thing, and the widely respected Macroeconomic Advisers — who wrote the most blistering critique of Heritage that I’ve seen — put it this way (footnotes removed):

NationalJournal reported that Nigel Gault – an economist at IHS Global Insight, whose model Heritage used — was incredulous about the output:

Menzie Chinn also weighed in several times on the Heritage analysis. As did Brad DeLong. As did Mike (MISH) Shedlock. And Calculated Risk (CR). And Bonddad. I am still looking for economists/bloggers who – having thoroughly examined the Heritage analysis – have given it their blessing. And, to be clear, that’s not, “Yeah, it’s the conservative/Tea Party position so I’m all for it.” I’m looking for, “Yeah, I have examined these numbers with a fine-tooth comb and they work.” So, to recap: The Heritage analysis has been found wanting by Krugman, DeLong, Chinn, Shedlock, CR, Bonddad, Macroeconomic Advisers (among others), and seriously questioned by IHS Global Insight, whose model Heritage used. Apologies to any econ blogger I may have missed who’s weighed in on this. Yet Heritage, instead of addressing the concerns of its various critics, chooses to go after only Krugman. Why? My guess is that, given Krugman’s liberal leanings, the path of least resistance for Heritage is to simply point at him — to the exclusion of all others — cry “liberal with an agenda,” take their ball and go home. Simply put, Krugman’s the low-hanging fruit. After all, Macroeconomic Advisers’ critique is much more thorough, detailed, and scathing than Krugman’s (“We believe that the main result — that aggressive deficit reduction immediately raises GDP at unchanged interest rates — was generated by manipulating a model that would not otherwise produce this result, and that the basis for this manipulation is not supported either theoretically or empirically. Other features of the results — while perhaps unintended — seem highly problematic to us and seriously undermine the credibility of the overall conclusions.”); why not take them on? Because this exercise is simply not about the facts, the data, or arguing on the merits (or lack thereof) – it is about labeling one’s opponent an ideologue and hoping that’s good enough to discredit him and end the argument. Stay tuned. |

| Posted: 19 Apr 2011 12:15 PM PDT Readin’ is good for ya:

What choo readin’ (when ya aint datin’ yer cuzins?) |

| Gramatik Remix: Led Zep Stairway To Hip-Hop Heaven Posted: 19 Apr 2011 11:41 AM PDT |

| Posted: 19 Apr 2011 11:30 AM PDT April 18th I've been "near-term bullish" for several weeks now and I perpetually feel like I need to run home and take a shower. This is not a rally that we Americans ought to be proud of. It is, however, a rally that is in progress and despite the poor risk/reward that it offers, and despite the inevitability of it ending at some point, professional traders are only fighting the tape (and officially sanctioned chicanery) by going short. For investors, assuming any still exist, my counsel all along – since before the financial crisis – has been to own Treasuries of short duration and gold. That is how my own meager savings are positioned. I've been told that owning Treasuries and gold is a schizophrenic or self-contradictory asset allocation, but I choose to view it as more of a barbell strategy that provides exposure to the only two solutions to our over-indebtedness: let creditors take the pain via inflation of money (long gold) or let debtors take the pain via deflation of credit (long Treasuries, while gold wouldn't necessarily do poorly in real terms either). The beauty of this position, which I envision as a 20-30% gold, 70-80% Treasuries mix but which can be adjusted as circumstances warrant, is that it's difficult to envision both asset classes performing poorly at the same time. In option speak, you're long a straddle on price stability. As with any straddle, the idea is to take a loss on one side of the bet while the gain on the other side of the bet offsets – and then some – the loss. In an inflationary spiral, Treasuries takes a hit but gold becomes more attractive. In a debt deflation, nominal losses in gold are offset by the enhanced purchasing power of your dollar (Treasury) claims. I must concede at this point that policymakers have engineered a "muddle through" situation in which neither inflationary spirals nor crushing debt deflations are present. This is a peculiar, not-particularly-desirable muddle through, however, and both gold and short duration Treasuries have outperformed most other assets including U.S. equities since the financial crisis began.* So, while my asset allocation is set up for severe-but-offsetting losses and gains, the reality has been much different. Why has this happened? Why has my asset allocation outperformed despite what appear to be relatively stable prices? There are two ways to look at this, one of which is a more domestic perspective while the other is global: 1. U.S. policymakers are obsessed with the wealth effect and have changed rules, laws, the value of the currency and investor perceptions such that all financial assets – be they risk assets or flight-to-safety assets – have risen in value (or nearly so, in the case of the equity market recovery). Discrepancies in performance across asset class are incidental. 2. The Fed's attempts to weaken the dollar have led to countervailing actions by Asian/OPEC countries which have in turn benefitted gold and other commodities. Meanwhile, the lack of observable inflationary pressure in the goods and services markets in the U.S. has been a fig leaf for those same Asian/OPEC countries as they recycle dollar surpluses back into U.S. Treasuries. I believe that both of these explanations have merit. Let's address each of them in turn. 1. The "it's all been set up to go higher" theory. This theory plays a large part in my near-term bullishness on the equity market as well as my bullishness on Treasuries. I'll provide two examples which have less to do with "chicanery" (which, it must be said, is present – see the Zero Hedge post titled "Doubling Down to (DXY) Zero" for an example) than with institutional structure and incentives. Example #1: The Fed's zero interest rate policy has created a problem for pension funds' defined benefit plans and for insurance companies offering fixed annuities: collectively, they have promised their beneficiaries a nominal rate of return that they cannot achieve without moving out on the risk curve or increasing the duration of their portfolios. The result is a mechanical appetite for any asset that clears a risk/reward hurdle which has been lowered, if not knocked over completely, by the Fed. I used to work with a bond salesman who covered insurance companies. These insurers are not playing a "spread" game – that is, they aren't terribly concerned with how they are being compensated for credit risk. My bond salesman friend used to tell me, "When Treasury rates back up, these guys love it because they can pick up high quality corporates with respectable yields – 5%, 6%." The reason the insurance companies "love it" is that they've locked in a respectable nominal yield that only needs slight augmentation from an equity, private equity or commodity exposure in order to get them up to the 8-10% that most of them have promised their beneficiaries (that figure comes from www.freeannuityrates.com). Meanwhile, insurance companies and pension funds with longer-term liabilities are happy to lock in 4.5% on a 30-year government bond in order to reduce their asset-liability mismatch. Example #2: Policies favoring short-term financial performance over long-term performance in the corporate sector have seen the supply of equity capital shrink while the use of debt capital has increased. Blame for this phenomenon once again falls at the feet of the Fed. By bailing out the likes of Harley Davidson, Verizon, Caterpillar, McDonald's and Toyota with emergency funding during the financial crisis, the Fed sent a message to investors and corporate managers that the equity capital "buffer" need not be large. Furthermore, the zero interest rate policy allows the corporate sector to borrow cheaply, providing another powerful incentive to issue debt rather than equity. As the supply of equity stagnates or is reduced, which the Fed's Z.1 Flow of Funds report suggests is happening particularly in the nonfinancial sector (see table F.213), prices are supported. 2. The "Bretton Woods II" theory. First, let's address whether or not the Fed's quantitative easing scheme is actually inflationary. Think of financial asset markets as markets where the various claims on cash flows are priced. Some are equity claims and some are debt claims, and those with title to the claims are either owners or creditors. All quantitative easing has done is force commercial banks to operate with a more liquid mix of assets, which has enhanced the perception of liquidity in the markets for those claims. The chart on the following page shows that as bank reserves have expanded, banks' "cash assets" have expanded apace (the original source is the Fed's H.8 report). Banks are taking the Federal Reserve Notes they receive from the Fed's QE operations and depositing it back with the Fed in order to pick up 25 basis points. Thus, it has ceased to become yield-less "cash" and is now a "cash asset" that earns a fixed rate of return. If commercial banks choose to monkey around with the cash before depositing it with the Fed overnight, they can of course do that, but in order to reconcile such behavior with the Fed's H.8 (which shows declining holdings of "other securities," a category which includes equities and other risky assets – see the chart directly above), they would need to be buying and selling in equal amounts throughout the week. So, it's questionable whether or not the "cash" generated by the Fed's quantitative easing program is having any direct effect other than the liquefaction of bank asset holdings. It's probably more accurate to say that policymakers are validating creditors' and owners' claims by way of a vague, poorly understood, perpetual promise to ensure ample liquidity. Because there is no direct inflationary impact from quantitative easing, we have seen price stability (if not outright deflation) in non-tradable U.S. goods and services. Asian and OPEC nations, which run large current account surpluses with the U.S., must keep those surpluses dollar-denominated in order to maintain their export advantage. The only market liquid enough to absorb these "recycled" dollars is the U.S. Treasury market, and given the aforementioned "core" price stability the Asian/OPEC nations can use that market as a repository without looking reckless. Treasury yields are thus held down while the inflation generated by their mercantilist policies creates a global bid for stores of value like gold. In conclusion, my initial, U.S.-centric reasoning for the barbell strategy was flawed, but global forces have underpinned the strategy anyway. * From June 29th, 2007 to present, 2-year Treasury notes have returned +16% or 4% annualized, spot gold has returned +129% or +24% annualized, and the S&P 500 Index has returned -5% or -1% annualized (all measured on a total return basis). A basket of emerging market equities, using the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets Index as a proxy but not including dividend reinvestment, has returned +12% or +3% annualized. (source: Bloomberg) References "Doubling Down to (DXY) Zero," by Tyler Durden |

| Geithner Interview on U.S. Budget Posted: 19 Apr 2011 11:25 AM PDT Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner discusses the U.S. budget deficit. Geithner, speaking with Peter Cook on Bloomberg Television’s “In the Loop,” also discusses banking regulation and the European debt crisis. autoplay video after the jump

|

| Posted: 19 Apr 2011 10:52 AM PDT |

| Posted: 19 Apr 2011 10:42 AM PDT |

| Posted: 19 Apr 2011 10:30 AM PDT |

| Playing Chicken With Federal Debt Ceiling Posted: 19 Apr 2011 08:30 AM PDT Bloomberg Businessweek on the debt ceiling: “Forcing a U.S. default is no small matter, yet many Americans say they want just that. It’s time for cooler heads on Capitol Hill to step up and lead.” I love this graphic: > Source: |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

0 comments:

Post a Comment