The Big Picture |

- A Credible Solution to Europe’s Debt Crisis: A “Trichet Plan” for the Eurozone

- Monday Reads

- Mac vs PC People

- Silver

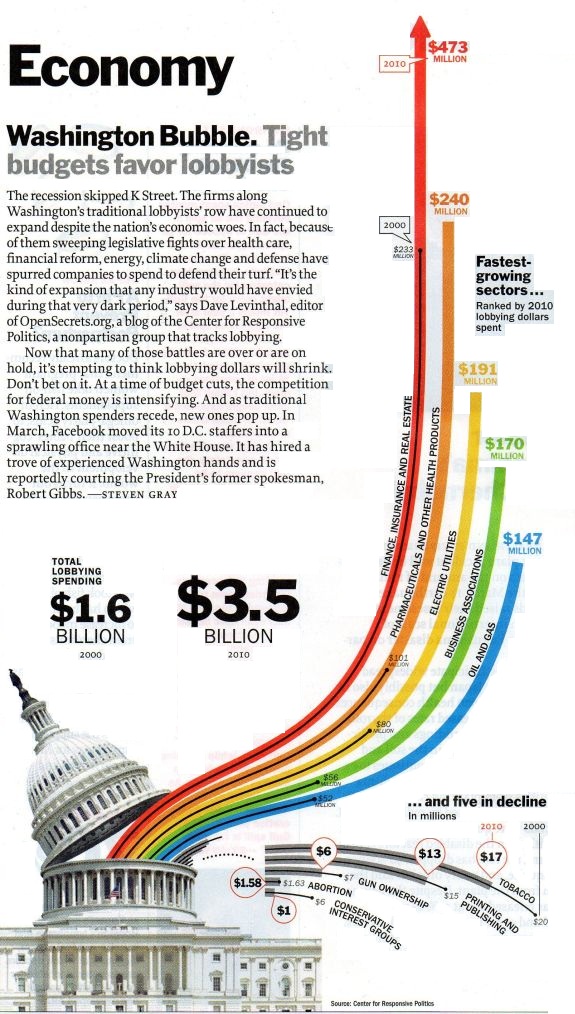

- The Lobbying Bubble

- New Home Sales Fall 22% Year Over Year

- The Power of Words

- Is It 1994 Again?

- Cheapest Homes in 40 Years? Not Even Close…

- He’ll talk about monetary policy but will he say US$?

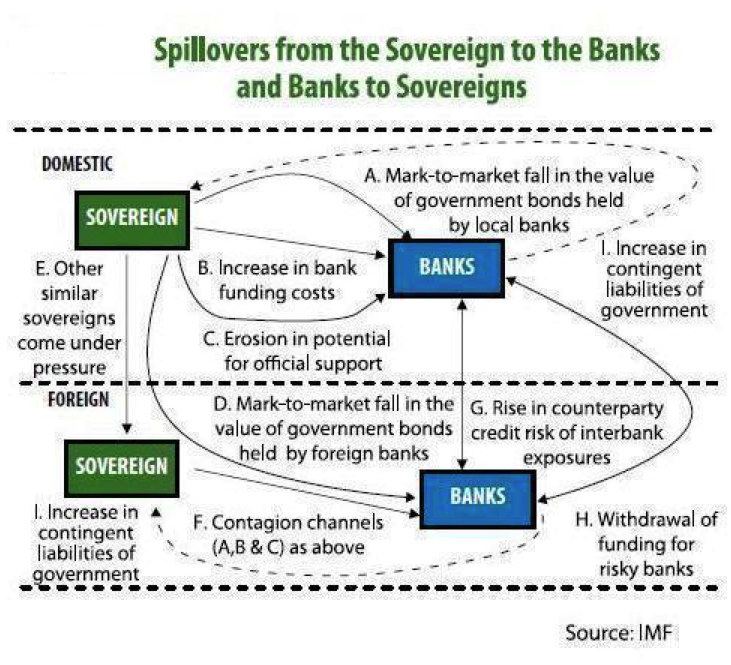

| A Credible Solution to Europe’s Debt Crisis: A “Trichet Plan” for the Eurozone Posted: 25 Apr 2011 10:30 PM PDT A Credible Solution to Europe's Debt Crisis: A "Trichet Plan" for the Eurozone Executive Summary In April 1989, Mexico's external debt negotiator, Angel Gurria, asked his country's commercial bank creditors for a 55 percent haircut. This was the opening pitch of the newly created Brady Plan, which finally addressed both the debt overhang of developing countries and the weak balance sheets of their commercial bank creditors, ultimately resolving the LDC Debt Crisis. More than twenty years later, Europe is in the midst of a similar sovereign debt and banking crisis. The EU is in a destabilizing feedback loop that it cannot control. Sovereign credit is deteriorating and this is reducing confidence in national banking systems, causing or increasing the likelihood that sovereigns will have to assume bank liabilities. This further impairs the sovereign credit and increases the lack of confidence in the banks. We review the basic tenets of the Brady Plan in the context of our personal experience working on many of these sovereign restructurings and how they could apply in a comprehensive solution for the European debt crisis. The markets and the Eurozone desperately need a positive confidence shock in the form a comprehensive plan that simultaneously addresses the sovereign debt overhang and the balance sheets of European commercial banks. Introduction It will be twenty-two years ago this month when Mexico's external debt negotiator, Angel Gurria, now Secretary-General of the OECD, fired the first pitch of the Brady Plan, named after the Treasury Secretary of new administration of President Bush #41. President Carlos Salinas of Mexico had taken office just four months earlier and stated his administration's debt policy while campaigning: "If we don't grow, we don't pay." He believed that only after addressing the debt overhang could Mexico return to stable economic growth. The LDC debt crisis (Less Developed Counties) erupted seven years earlier in August 1982 when Mexico declared a 90-day moratorium on external debt payments. Tight monetary policy in the U.S. had driven up interest rates and, coupled with falling commodity prices, impaired the capacity of these countries to refinance their external debt. Most of the debt was medium term loans at floating rates of interest (three or six-LIBOR plus a spread) to commercial banks in France, Germany, Japan, Italy, Switzerland, the UK and the US. Economic and Political Crisis Similar to the current situation in the Eurozone, the LDC debt crisis was really two major problems, which, in its early stage created an unstable feedback loop. It was first an economic problem which morphed into a political crisis for many highly indebted sovereigns. Second, it was a banking crisis.

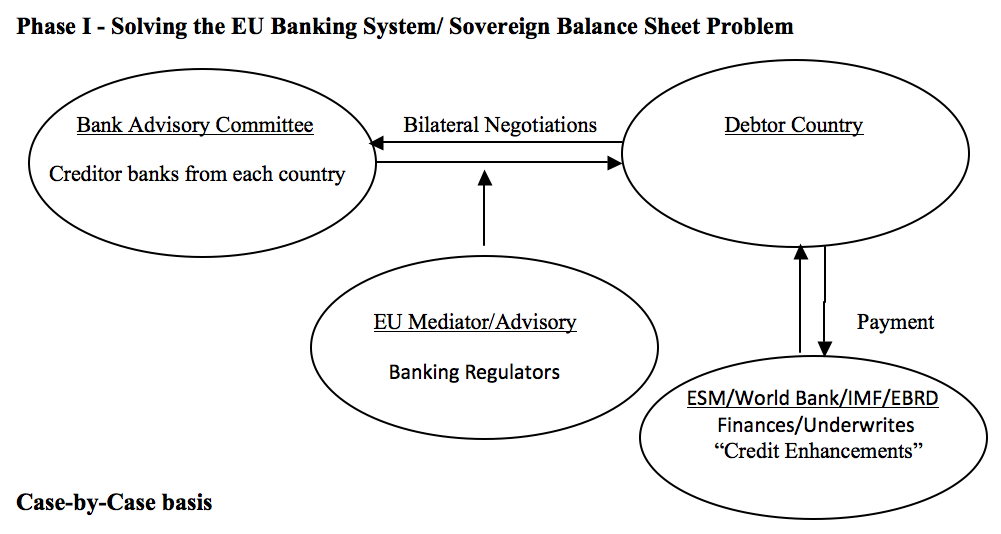

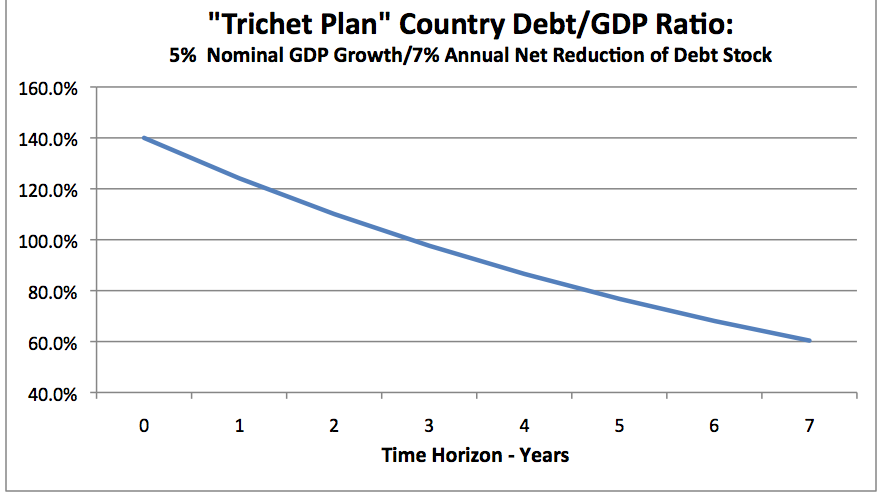

Second, the LDC Debt Crisis was a commercial banking crisis. Many of the large global banks were heavily exposed to LDCs and some faced losses that approached their equity capital. Faced with this threat, the international financial community fashioned a coordinated response that managed to stabilize things for about six years. They negotiated agreements almost every year for each country rolling over (or rescheduling) loan principal payments and extending new loans to keep interest payments flowing. BofA had been slowly building reserves but not enough to cover the secondary market discounts and a forced mark-to-market would have driven the bank to the brink of insolvency. The bank had great cash flow generation from its consumer businesses but needed more time to "grow" out of the LDC debt problem. Though the markets were becoming impatient, the bank was increasing reserves and slowly selling down portions of its LDC portfolio. A mandatory mark-to-market would have been disaster. We spent many hours in those days on talking points to counter the Congressional pressure for mandatory write downs. Banks on the BAC carefully negotiated the terms of each option to ensure that the international banking community could live with the haircut and could choose the form in which the haircuts would be granted. They structured options to optimize capital under the different accounting, tax, and regulatory regimes of the international banking community. The goal of many banks, including BofA, who understood the new Brady bonds would continue to trade at large price discounts in the secondary market for some time, was to structure a deal that would prevent a mandatory mark-to-market of their LDC portfolio. By protecting equity capital and allowing the losses to be spread over a longer time horizon a significant reduction in bank balance sheets was averted. Just about half of Mexico's banks chose the Par Bond option. This bond had a semi-annual coupon, of 6.25 percent (at the time six-month LIBOR was close to 10 percent) and allowed the original loans to be converted a "par" with no reduction in principal. A bullet principal payment was due in December 2019 and was collateralized in full by U.S. Treasury zero coupon bonds. The bond included a mechanism, which would collateralize three semi-annual coupon payments and roll forward every time Mexico made a payment. U.S. banks used the FASB 15 accounting rule to avoid a write-down when they swapped their loans for Brady bonds. The rule allowed for restructured loans kept as long-term investments to be booked at original face value if the sum of nominal income and principal payments exceeded the original loan extended. Conversely, some European banking regulatory and tax agencies made the Discount Bond relatively more attractive, as their policy was to incentivize banks to reduce their LDC exposure. The Discount Bond was exchanged at 65 percent of the original loan amount for a floating rate 30-year bond. The bond had a semi-annual coupon of Libor plus 13/16 percent and bullet principal payment in December 2019, collateralized in full by U.S. Treasury zero coupon bonds. It also included the same interest collateral as the Par Bond. Value Recovery Rights The Mexico Par and Discount bonds included a value recovery mechanism linked to Mexico's oil revenues. The mechanism required Mexico to pay up to an annual 300 basis points in extra coupon payments in the event the Pemex oil price and export volumes exceeded a certain negotiated threshold beginning six years after issuance. We helped design and negotiate the value recovery mechanism and recall many bankers predicting that they "would never see a dime of recovery value." To their surprise, Mexico made payments under the value recovery in the first year of eligibility in 1996. This helped to motivate Mexico to buy back and retire its Brady Bonds almost twenty years before they matured. If Mexico's 6.25 percent Par Brady Bond were still outstanding and trading today, the oil-linked value recovery rights would be deep in the money and paying at the maximum 300 bps per annum. The Par Bond would be trading close to a price of 150% of face value, providing a 16 percent plus hypothetical annual return if the bond was purchased at market value at the date of issuance. This compares to a 6 percent annual return on the S&P 500 over the same time period. Mr. Gurria insisted that the agreement allow for early retirement of the bonds through buybacks or market exchanges. Many bankers on the BAC did not take Mr. Gurria seriously on this point as they believed the country would be back at the negotiating table sooner rather seeking more debt relief. Many bankers, jaded by seven years of annual rescheduling negotiations ad infinitim, simply could not imagine that the Mexico's debt crisis was about to be resolved with a single transaction. European Sovereign Debt Crisis The Eurozone is in a destabilizing feedback loop that it cannot control. Sovereign credit in the periphery is deteriorating fast and this is reducing confidence in the region's banking systems, causing or increasing the likelihood that sovereigns will have to assume bank liabilities. This further impairs the sovereign credit and increases the lack of confidence in the banks Europe needs a plan with the same two objectives as the Brady Plan: 1) reduce the debt overhang of the periphery sovereigns; and 2) bolster the balance sheets of the banks and preserve their capital by controlling the form and magnitude of losses that they will have to realize. Haircut Realized Over Several Year Time Horizon If not already on the books, the Financial Stability Board may need to write specialized accounting and tax regulations for the "Trichet Plan." This would be similar to the benefit of U.S. FASB 15 accounting for US banks in the Brady plan. How best to do this, though, would hinge on an analysis of the banks' balance sheets, especially their holdings of this debt, the availability, if any, of dedicated capital, and the strength of income from other assets. The second phase would launch an offer with comparable terms to all non-bank bond holders and non-EU banks. This phase could also be negotiated, but this may not be necessary if the first phase establishes a new benchmark bond or two, with liquidity by virtue of having been chosen by the largest bank creditors. Phase one will determine all of the major terms of the secondary exchange offer, though some terms might be tailored to non-bank creditors. A "Trichet Plan" must also be flexible and deal with each country on a case-by-case basis. For example, during its Brady negotiations, Brazil said that it had up front access to only $2 billion of collateral, far short of the amount needed to cover the choices banks were expected to make from Brazil's Brady bond menu. Brazil's commercial bank debt was $50 billion. The banks wanted full collateralization at the close of the deal and the Brazilians refused, arguing it couldn't afford it. This caused negotiations to stall. Because Brazil said it could access more funds from the IMF and World Bank to purchase the collateral over time, we designed temporary Phase-in Bonds, which gave Brazil no debt relief and relatively onerous terms, which Brazil would call and exchange for Brady Bonds when the cash collateral was obtained. This satisfied both banks and the Brazilian government and worked very well allowing the restructuring to close probably years before than would have been the case. Another example of case-by-case flexibility of the Brady Plan was the size of haircut. The haircut was a central element of negotiations and varied depending on the needs of the case at hand. Early Brady countries, such as Mexico (1990), Venezuela (1990) and Uruguay (1991) had smaller debt overhangs and received debt reduction in the neighborhood of 30-35 percent. Later Brady countries, such as Poland (1994), Panama (1996) and Peru (1996) had bigger debt overhangs in part because of a need to capitalize larger past-due interest claims. These countries negotiated haircuts in the neighborhood of 45 to 50 percent. Yet another example of case-by-case flexibility is Uruguay's value recovery warrants. Unlike the oil-linked value recovery mechanisms in Mexico and Venezuela (both of which paid), Uruguay's value recovery was a modified terms-of–trade index. We included in the numerator the price of the country's main exports, wool, beef, and rice, and because the country imported oil, the denominator was simply the price of crude oil. Value Recovery One alternative that has been suggested is GDP warrants. This type of facility would require the sovereign to make extra coupon payments in the event an index of its real GDP were to surpass a certain threshold after a period of grace of ten years or so. Value recovery of this sort has been used successfully in a number of cases, including Costa Rica in 1990 and Argentina in 2001. Other alternatives might include an index linked to an international price such as a commodity price or market or industrial index which directly impacts and provides the debtor country with windfall revenues or expenditure reductions. Special Accounting and Tax Treatment for Restructured Debt A "Trichet Plan" needs first to address the balance sheets of the banks. An exchange offer with a menu of options could easily be crafted in which enhanced "replacement bonds or credits" can resolve debt overhangs and be tailored to the needs of the banks. These instruments could spread the haircut over several years. This could be achieved in different ways. One possibility, for example, is a FASB 15-style conversion of old bonds for new Par Bonds with losses realized quarter by quarter as coupon payments received fall below banks' funding costs. Another possibility is enhanced step-up fixed or floating rate Par Bonds or front-loaded interest reduction bonds. Alternatively, a discount instrument could phase in the discount (reduce the face amount of the bonds) over time, say 5-10 percent per annum over a seven year period, a "Phase-in Discount Bond," for example. Similar to Poland's Paris Club deal, the discounting of the principal and interest reduction in each year would be linked to the country remaining current in an IMF program. This would have the benefit of ensuring a reduction of the debt stock, while incentivizing fiscal and economic discipline. Unlike other European debt proposals, we believe that the stakeholders, both borrower and lender, with some guidance from EU regulators, should take the losses. They should set the terms of the restructuring, and design the instruments in a menu of options, which fits their best interests. The "Trichet Plan" deals first with overexposed Eurozone banks and will alleviate the fear of banking collapse and Lehman-like systemic contagion, which has made even the talk of restructuring a "taboo" topic. Furthermore, the pragmatic and more realistic structure will relieve political pressures in the European core as the bailouts will stop and insolvency issues will finally be addressed. The principles we have outlined here are proven and pragmatic; they were the core of the successful resolution of the last major sovereign debt crisis, and have been accepted by global capital markets and the international financial community. EFSF/ESM Funds for Banking Recapitalization The EFSF/ESM funds, currently being used and earmarked for the sovereign bailouts, could then be used more effectively to recapitalize and further strengthen the Eurozone banking system, for example. If designed and executed correctly, the political friction within the Eurozone could fade as taxpayers in the core countries, rather than assuming the debt of the periphery, could actually profit from such a recapitalization plan. Debt-for-equity, education, environment and poverty swaps Debt-for-poverty swaps could allow charitable organizations to purchase the bonds to pay for government services, public lands for food production, or public buildings for low income housing. These swap mechanisms could be carefully designed to be additive on a fiscal basis as not to substitute for current revenues. The subsidy of the swap, the difference of the secondary price and redemption value, would incentivize the private sector to create public goods. In addition, the debtor country would retire debt by capturing most of the secondary market discount. Long-term Perspective: "Seven-year 5 and 7 Plan" In a hypothetical example, if a "Trichet Plan" country with an initial 140 percent debt to GDP ratio can grow by 5 percent per annum (in nominal terms) over a seven years, while, at the same time, reducing its net debt stock by 7 percent every year, the Debt/GDP ratio would decline to 60 percent of GDP. Conclusion We think that the EU has a range of good options for structuring enhanced replacement bonds, which would have an implicit seniority, contingent guarantees, value recovery mechanisms and debt swap provisions. This structure would be a much more efficient, less costly and more politically acceptable and sustainable use of EFSF and IMF funds than what we have seen so far. The special EFSF programs could be redirected to make contingent financing available to sovereigns in the form of stand-by letters of credit for partial guarantees on the issue of replacement bonds. These enhancements could take many forms, such as guarantees on all or portions of principal due at maturity or according to an amortization schedule, or guarantees on portions of coupon interest. By first focusing on bolstering European bank balance sheets and dealing with their sovereign exposure to the periphery, the fear of systemic contagion of a European sovereign restructuring would be greatly reduced. Furthermore, a bold and comprehensive "Trichet Plan" seems to be the only way to break the vicious feedback loop Europe finds itself in. Our proposal, unlike other European debt proposals, is predicated on the notion that the borrowers and lenders and not outside parties should take the losses, set terms of the restructuring, and design the instruments in a menu of options which best fits their needs. The consenting adults who created Europe's crisis are the ones who should resolve it – albeit with assistance from EU regulators and officials There is much at stake, not just for Europe, but the rest of the highly-indebted West. Forbearance by piling debt upon debt to deal with what is ultimately an insolvency issue is no longer an option in the Eurozone and further stumbles could increase global systemic risk. Policymakers should not entirely discount the risk that the crisis in the periphery could spread to the core of Europe and even skip across continents and oceans. ~~~ The authors wish to thank Barry Eichengreen for his valuable comments on this article. * Gary Evans is an independent trader and economist. At Bank of America, he worked on several Brady Plan sovereign restructurings, including Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Poland. He was Poland’s financial advisor during their Brady Plan and headed several emerging market bond trading desks. He began his career at the World Bank in the mid-1980′s. gevans33-at-msn.com * Peter Allen is an economist living in Northern California. He is a specialist in sovereign debt restructuring. As Vice President of Bank of America, he worked on the Brady Plan restructurings for Uruguay, Ecuador, Brazil, and Argentina. He later served as a special advisor to the Governments of Poland, Panama and Vietnam. Most recently he advised bondholders in the sovereign restructurings by Russia and Argentina. peterallen -at- vom.com |

| Posted: 25 Apr 2011 01:30 PM PDT Some interesting reading to start off your week:

What are you reading? |

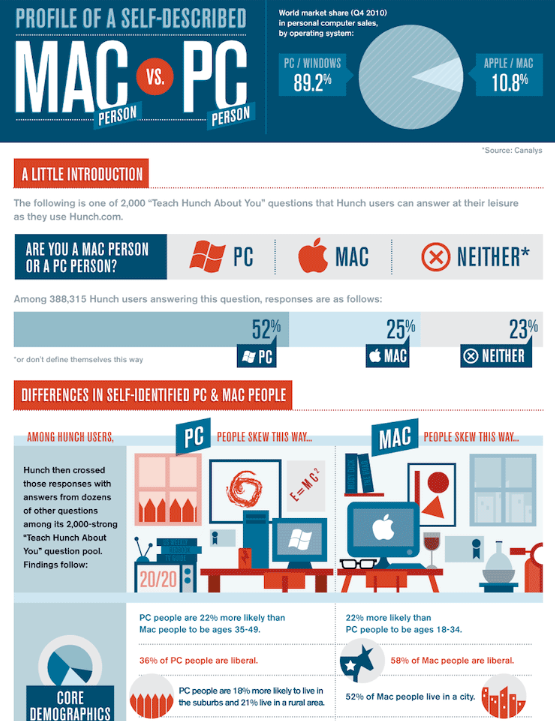

| Posted: 25 Apr 2011 11:30 AM PDT Mac users are more politically liberal, more urban, younger and more educated than their PC-using counterparts. That is according to a new survey by affinity aggregator Hunch. Among the more interesting findings:

There is a great infographic on this, from Hunch and Column Five:

click for ginormous graphic > Sources: |

| Posted: 25 Apr 2011 08:46 AM PDT With the 14 day RSI rising above 90 this morning in silver, reflecting the parabolic nature of its recent move, all it took was a slight $ bounce against the euro after the early morning’s weakness to get silver and other commodities to reverse course. In terms of the broader market, silver is a great gauge to watch both in its non $ play, gold friend play of course and industrial use/global growth story but also the momentum game in the short term as markets play a game of chicken with the end of Fed Treasury purchases in two months. |

| Posted: 25 Apr 2011 08:30 AM PDT In the podcast I did with Dylan Ratigan last week, I mentioned we needed a Constitutional amendment mandating public funding of all federal elections. It seems to be the only way imaginable to get all of the dirty money and corporate lobbying efforts out of each and every attempt to close tax loopholes, reduce overall spending, and fix the tax code. As if on cue, Tim Iacono points to this outrageous chart (via Time Magazine) showing how much dirty lobbying money has poured into DC over the past decade: > Source: Time magazine. > If you want to understand why the problems in DC are intractable, start with that graph above. > Previously: |

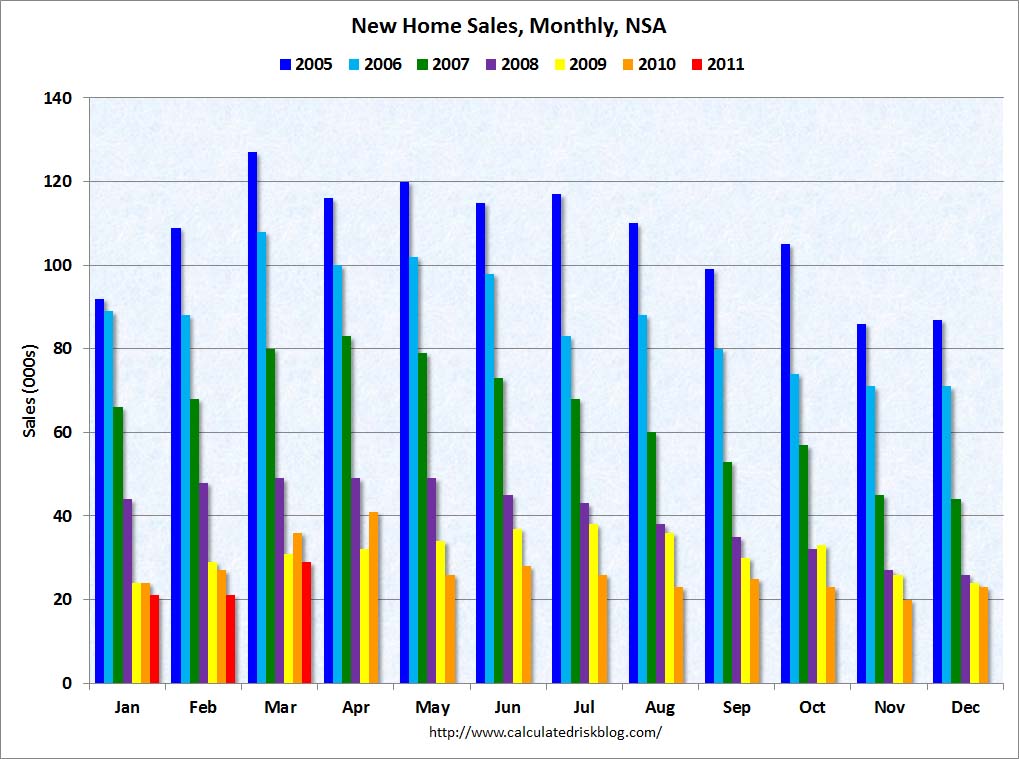

| New Home Sales Fall 22% Year Over Year Posted: 25 Apr 2011 07:34 AM PDT

Note the margin of error. The monthly gain of 11% is not statistically significant with an error of +/- 21.7%. On the other hand, the year over year drop of 21.9% is statistically significant with an error of +/- 11.1%. > New Home Sales (March 2011)click for larger chart |

| Posted: 25 Apr 2011 06:00 AM PDT This short film illustrates the power of words to radically change your message and your effect upon the world: Created by RedSnappa (www.redsnappa.com) Homage to Historia de un letrero, The Story of a Sign by Alonso Alvarez Barreda |

| Posted: 25 Apr 2011 05:30 AM PDT

His new book, Panderer for Power: The True Story of How Alan Greenspan Enriched Wall Street and Left a Legacy of Recession, was published by McGraw-Hill in November 2009. He was Director of Asset Allocation Services at John Hancock Financial Services in Boston. In this capacity, he set investment policy and asset allocation for institutional pension plans. ~~~ There are several similarities between current trends and those in 1994, a year when many institutions were left destitute. Historical analogies can help us imagine what might happen, but identification of differences should be noted too. The greatest dissimilarity is probably the structure of markets. There was some official (government-sponsored) interference in 1994, the most obvious being the Federal Reserve’s authorized pegging of interest rates. There was, however, no comparison to the government’s merrymaking in 2011. Official policy to boost the stock market is well known. See, for instance The Fed Underwrites Asset Explosion. Rumblings that the Federal Reserve is writing put options on U.S. Treasury securities circulate, the particulars of which can be read on various websites and in the Financial Times (see: ft.com/alphaville: “More on the Literal Bernanke Put,” April 18, 2011.) The result of such interference is, or, would be, (depending on your inclination), to relieve fears of bondholders. The risk of falling prices is transferred to the party that has written the put. The Fed is (would be) absorbing losses if Treasury bond yields continue to rise and prices fall. (The latter is often forgotten but is important since balance sheets suffer losses and collateral falls: leading to calls for additional collateral.) All government interference in security markets fails. The Fed’s monopolized control and underpricing of short-term interest rates failed when the Internet and mortgage bubbles burst. Today, whether or not the Fed is writing put options to attract buyers of Treasuries is not as important as the knowledge that there are few interested buyers of an unhedged, 2-year Treasury note (0.70% yield) or a 10-year Treasury bond (3.5%). The Fed-sponsored put option is the logical next step to dampen the yield curve. The analogy to 1994 is to an earlier time when the government could no longer control interest rates. Yields were too low and bond prices too high. Once rates did rise, there were several consequences. Many were related to untested and overmarketed derivative products. Institutions failed, some of high reputation, because they did not understand the derivatives that were making their clients rich (and suddenly poor). As we’ve seen time and again, “stress tests” of derivatives (and of banks) are paper exercises that cannot account for unforeseen divergences or convergences of markets that have been mangled. Many institutional and retail investors were caught in the grinder. An autopsy of 1994 may help today’s investors avoid similar mistakes. Then and now, the Fed had reduced interest rates to a microscopic level (from 9-3/4% to 3%), which had chased investors out of money markets and into the stock market. Net cash flows into stock mutual funds rose from $13 billion in 1990 to $79 billion in 1992 and to $127 billion in 1993. In 1992 and 1993, money market funds suffered net outflows. Then and now, the banking system needed a bailout. Then and now, the Federal Reserve assisted financial gimmickry to boost a floundering economy. Commercial real estate was the greatest offender in the early 1990s. Citicorp and others had stopped lending. Banks borrowed Treasury bills at 3% and bought Treasury bonds that paid 6% yields.

This was the carry trade. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan launched the carry trade in the early 1990s, for which he claimed a patent at the September 2004 FOMC meeting (See “The 2004 Fed Transcripts: A Methodical, Diabolical Destruction of America’s “Wealth.” Several iterations later (of raising and cutting rates), have shown not only that superficial finance suffocates the real economy, not only that deeper and deeper cuts are less stimulative, but also that each new fix in finance must be more intrusive and crippling to markets. In 1994, unhealthy securities were fashionable. More importantly, novice securities produced wholly unanticipated results when markets collided. Seemingly sophisticated investors learned they had not appreciated the risks they were bearing. Unanticipated correlations were imbedded in highly marketable derivative products. Today, derivatives are far more complex and the magnitude is incomprehensible. J.P. Morgan, a single bank, holds $78 trillion of derivative contracts. About 84% of all U.S. commercial banking derivative contracts ($231 trillion in total – all told, over a quadrillion dollars of contracts exist in the world) are interest-rate related at a point when interest rates can only go in one direction. A failed Treasury auction could boost interest rates by 4% in seconds. The banks say “We’re hedged.” Well, maybe this will turn out swell, but it is hard to grasp how the twists and turns of a commercial-bank, derivative book almost 15 times the size of the United States’ GDP (around $15 trillion) can be anticipated when markets devour unmodeled deviations. Then and now, derivative protection against rising rates is selling. From The Credit Bubble Bulletin, April 8, 2011: “The biggest year since 2003 for the packaging of U.S. government-backed mortgage bonds into new securities has extended into 2011, bolstered by banks seeking investments protecting against rising interest rates. Issuance of so-called agency collateralized mortgage obligations, or CMOs, reached $99 billion last quarter, following $451 billion in 2010…” Then and now, the Federal Reserve – specifically, the FOMC – was too slow to raise rates. Discussions at current FOMC meetings will not be released to the public until 2016, but debate in late 1993 may have generated a similar edge. Larry Lindsey was the Federal Reserve governor who upset the applecart, or at least, the chairman, Alan Greenspan. In September 1993, FOMC members David Mullins and Lawrence Lindsey expressed concern of a ‘speculative bubble’ in the stock and bond markets. Mutual fund flows from the U.S. had recently driven stock markets to all-time highs in Hong Kong, Bombay, and Botswana. In November, Boston Chicken’s shares appreciated 243% on the first day of trading. The stock sold at over 100 times sales – not earnings. This was the beginning of the public’s consciousness of an acronym – IPO – that previously had been a Wall Street insiders’ term. Federal Reserve Governor Lindsey stated at the December 1993 meeting: “[W]e all agree that the 3 percent [funds] rate is unsustainable. We all know it is too late.” That is, the FOMC should have raised rates earlier to forestall a certain degree of speculation. Lindsey noted a rush into $1 million home mortgages since, at current interest rates and forthcoming tax rates (which were going up for the well-to-do); this was “like borrowing money free for 30 years.” Lindsey expected “asset rediversification, a flow of funds into real estate and… out of dividend-paying stocks into OTC stocks.” “OTC stocks” would soon be rechristened “the Nasdaq” which rose from 760 to over 5,000 in about six years. After Lindsay warned about “asset rediversification” in 1993, he raised the Boston Chicken IPO as a sign of speculation, then suggested the Fed cook up its own fast-food IPO, asking: “What do you think, Al?” Nobody at the FOMC ever call Greenspan “Al” and very rarely “Alan.” First names were generally not used when FOMC members addressed each other. Transcripts are only words, but if a playwright’s annotations were called for, “scowl” is the impression when Larry spoke to Al. On January 31, 1994, Greenspan warned that “[m]onetary policy must not overstay accommodation.” The Fed chairman went on to say the FOMC would decide “when is the appropriate time to move to a somewhat less accommodative level of short-term interest rates… Short-term interest rates are abnormally low in real terms…” By early 1994, banks were liquid and lending. This, too, should have warned the carry-trade was coming to an end. This is in contrast to 2011, when large banks’ are not lending and owe their parasitic solvency to the Financial Accounting Standards Board. The Fed raised the funds rate to 3.25% on February 4. This one-quarter of one percentage point increase caused more financial destruction than any event since the 1987 crash. Margin calls drove prices lower and yields higher. This prompted more margin calls and more selling. Long-term Treasury yields rose from 6.3% in January to 8.0% in December 1994. February was just the beginning. The Fed continued to raise the funds rate to a peak of 6.00% in 1995. Greenspan probably did not anticipate the carnage. Nor, may he have anticipated how derivatives destabilized the financial system. The leverage in these contracts had contributed mightily to the recovery of the U.S. economy. The deleveraging could not have been a complete surprise. A comparison between Greenspan in 1994 to Ben Bernanke in 2011 is probably an empty exercise. It is unlikely that Simple Ben will ever raise rates. He is, after all, simple. Either the market or a successor will do so. That is my opinion though, so Greenspan’s reaction to rising rates in 1994 is presented as a case study that might shed some light on what the 2011 FOMC could think and do. It does not appear the flowering of imaginative finance was appreciated even after the Fed raised rates on February 4. Frank Partnoy’s book, Infectious Greed: How Deceit and Risk Corrupted the Financial Markets is an invaluable guide to the unraveling. Quoting Partnoy: “The New York Times took note of the panic among financial specialists on February 5…saying the Fed’s action sent an arctic blast through Wall Street.” On February 28, Chairman Greenspan told the FOMC: “I think we broke the back of an emerging speculation in equities. We pricked that bubble [in the bond market] as well….We have also created a degree of uncertainty; if we were looking at the emergence of speculative forces, which clearly were evident in very early stages, then I think we had a desirable effect.” The Fed would raise the funds rate to 3.50% on March 22 and to 3.75% on April 18, 1994. Askin Capital lost all of its money by April 7 – two months after the first rate hike. David Askin “was one of the largest and most sophisticated investors in mortgage securities. Askin was a respected trader…and was among the most active traders of complex mortgage securities. Often, Askin was the market.” (Partnoy) David Askin had marketed his fund as containing the “highest quality” securities. These would be hedged “so as to maintain a relatively constant portfolio value, even through large interest rate swings.” He may have believed this, yet two 0.25% increases in a short-term rate sank the $600 million fund. The fund advertised its “proprietary analytic models” which discovered mispricings among complex mortgage derivatives, such as Collateralized-Mortgage Obligations (CMOs). Askin and his models misunderstood the complexities and compounded the error with a high dose of leverage. He also made the common mistake of ignoring the markets (after the February 4 rate hike) and believing his models – which told him they were right and the markets were wrong. In hindsight it is easy to find fault with investors who lose money in a slingshot fund. Yet, it is also easy to understand why investors would trust Askin, given his experience, his reputation, and his domination of the market in which he invested. This is a warning to investors, in 2011: that it is worth the effort to understand the types of securities being managed in an account. Bond ratings are often camouflage for devious accounting tricks. ETFs are being launched so fast today, they cannot possibly be thoroughly vetted beforehand. More flash crashes should be expected. Standard asset allocation (as seen in the glossies and newspapers) is not the way to think about one’s assets when imbalances are bound to topple. Collateral behind derivative arrangements (such as ETFs) is obscure. At the April 18 FOMC meeting, Greenspan ventured: “[T]he sharp declines in stock and bond prices since our last meeting, I think, have defused a significant part of the bubble which had previously built up. We let a lot of air out of the tire, so to speak…” Possibly, but cascading losses had a long way to go. This was the date of the third rate hike, to 3.75%. Askin’s failure prompted an earthquake through the CMO market. Piper, Jaffrey, an old-line Minneapolis investment firm advertised the Piper Jaffrey Government Income Portfolio Fund as safe and secure. CMOs include mortgages that are backed by the U.S. government, so the fund remained within its mandates when the derivative securities rose to 93% of his holdings. As government-backed securities, they carried AAA-ratings. (There was no memory of unwarranted, AAA, U.S. government-sanctioned ratings in 2007. Why none of the regulators, rating-agency analysts, portfolio managers, CEOs were not arraigned…) The fund yielded over 13% – double the average of other government short-term bond funds. Something is mispriced here, but not the CMOs: more sophisticated traders called the securities “nuclear waste.” With the fig leaf of a AAA-rating, Piper, Jaffrey bought “inverse IO” CMOs, the payments from which correspond to the inverse of interest-rate payments of homeowners. Piper relied on Askin’s models to price its own securities. When Askin’s apparatus failed; Piper, Jaffrey could no longer value the portfolio. The fund manager resorted to calling brokers around the country and then released a weekly price. (Piper, Jaffrey was legally required to publish a daily Net Asset Value.) This garbage-in, garbage out methodology calculated the 1994 principal loss at 28%. The lesson for investors in 2011 is to look beyond a brand name. Piper, Jaffrey had a good reputation. The Piper Jaffrey Government Income Portfolio had some flaws. It was managed by a celebrity: Worth Bruntjen. The “Wizard of Mortgages” appeared on the December 6, 1993 front cover of Business Week. He dressed as General Patton at sales meetings. Unbeknownst to the human resources department, he had not graduated from college. The most prominent red flags were the Piper, Jaffrey ads: “THIRTEEN PERCENT RETURNS! Legislation was passed permitting municipalities to buy shares in the fund. About 60 did so. On May 17, 1994, the Fed raised the funds rate by 0.50% to 4.25%. On May 24, Greenspan told the FOMC members that “ever since the 1987 peaks after the stock market crash” uncertainty was diminishing and there was an element of euphoria that gripped the markets…we have taken a very significant amount of air out of the bubble…I think there’s still a lot of bubble around…. [W]e have the capability, I would say at this stage, to move more strongly than we usually do without the risk of cracking the system.” It is interesting that he estimated the damage done by raising rates had not and would not “crack the system,” probably meaning the credit system along with the stock and bond markets. This is in contrast to 1999 when Greenspan claimed the Fed could not identify a bubble and even if it could the Fed would do nothing other than sweep up the debris. Looking at 1994 now, Greenspan had (in his words) identified a bubble, was letting air out of it [sic], and The System was in fine shape. Yet, it was cracking. The deified investment bank at 85 Broad Street was bailed out. The largest publicly acknowledged casualty of all was Orange County, California, which lost $1.7 billion in derivative trades and was forced into bankruptcy. It had fallen prey to the pathetic County Treasurer, Robert Citron. (When asked how he knew interest rates would not rise: “I am one of the largest investors in America. I know these things”). To make a long story short, he bought AAA-rated issues of the Federal Home Loan Bank. The credit was sound but the bonds had been diced into inverse-floating rate structured notes. These were well beyond Citron’s comprehension. As such, his decision to leverage $7.4 billion worth of inverse-floaters with $13 billion lent by Merrill Lynch threw kerosene on the fire. It might be asked why a respected Wall Street firm did not observe more prudence when the borrower was so obviously untutored. Merrill was making too much money to care. Between 1990 and 1993, Merrill Lynch earned more than $3.1 billion, topping the total profits of its previous 18 years as a public company. Over $100 million of the profits were wired from the Orange County treasurer. Corporations were easy prey for investment banks. Merrill Lynch sold Preferred Redeemable Increased Dividend Equity Securities (PRIDES), Goldman Sachs marketed Automatically Convertible Enhanced Securities (ACES), Lehman unleashed Yield Enhanced Equity Linked Securities (YEELDS) and Bear Stearns created Common Higher Income Participation Securities (CHIPS). Other big losers include Air Products and Chemicals (which lost $113 million), Dell Computer ($35 million), Caterpillar Financial Services, Eastman Kodak, Gibson Greetings, Mead, Procter & Gamble, Cuyahoga County (Ohio), National Fisheries (South Korea), Postipankki Bank (Finland), Federal Paper Board, Wimpey Group, Silverado Banking Savings and Loan, City Colleges of Chicago ($96 million – almost its entire portfolio), the Eastern Shoshon Tribe, the Sarasota-Manatee Airport Authority, Lewis & Clark County (Montana), eighteen Ohio municipalities (the reader may note an implied, potential vaporization of municipal balance sheets – they are easy prey), and Sears. Firms in the money business also paid a heavy price. Investment managers NationsBank, Fidelity Investments, the Vanguard Group, First Boston, Cargill Investor Services, Metallgesellschaft, Yamaichi Securities, Shanghai International Securities, and Soros Fund Management suffered unexpected losses. Bankers Trust was hired by Gibson Greetings to hedge its interest-rate risk. At first the derivatives were simple. The strategies evolved into bizarre interest-rate swaps. For instance, Gibson Greetings received a fixed-rate, 5.5% interest coupon from its counterparty (Bankers) which received a floating-rate coupon equal to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) squared by itself and then divided by six. This was more fun than scriptwriting The Daily Show. A Bankers Trust managing director recalled: “Guys started making jokes on the trading floor about how they were hammering customers.” Gibson Greetings paid over $13 million in fees to Bankers over a 3-year period. The chairman of Bankers, Charlie Sanford, awarded the salesman a substantial bonus and sent an enthusiastic memorandum to the company when he announced the elevation. Bankers Trust honed its skills to a remarkable degree. Bankers earned $7.6 million from one interest-rate swap it sold to Procter & Gamble. The security was so complex that the company misunderstood its exposure to a change of interest rates by a factor of 17. What appeared to be an exposure of $200 million was actually a $3.4 billion bet that rates would remain low. More interesting than the trade (on which P&G lost $200 million) were the taped phone calls that cut to the heart of the derivative sales boom. Following is a conversation between Kevin Hudson, who sold the deal, and Alison Bernhard, a colleague: BERNHARD: “Oh, my ever-loving God. Do they understand… what they did?” HUDSON: “No. They understand what they did, but they don’t understand the leverage.” BERNHARD: “They would never know….” HUDSON: “Never. No way, No way. That’s the beauty of working at Bankers Trust.” These gimmicks were gathering headlines by the fall of 1994. It may have been fate, then, that entwined Bernhard and Hudson on November 5, 1994. The New York Times devoted a story to the managing director and the vice president of Bankers Trust. We read, under a lovely photograph of the pair: “Alison Ann Bernhard, a daughter of Dr. and Mrs. Robert Bernhard Jr. of New Orleans, was married yesterday to Kevin Walter Hudson, a son of Dr. Barbara W. Hudson and Walter Hudson of Baltimore. The Reverend Jeffrey H. Walker performed the ceremony at Christ Episcopal Church in Greenwich, Connecticut.” The happy pair were headed to London where they would ply their trade for Bankers Trust. It was misguided economists who sold the world on their efficient market hypothesis. It was the EMH on which the premises of the derivative models are constructed. Simple Ben worships at the alter. The models still do not address such pricing abnormalities as greed, pride, criminality and the most basic of motivations that led Bernhard & Hudson to the alter of Christ Episcopal Church. |

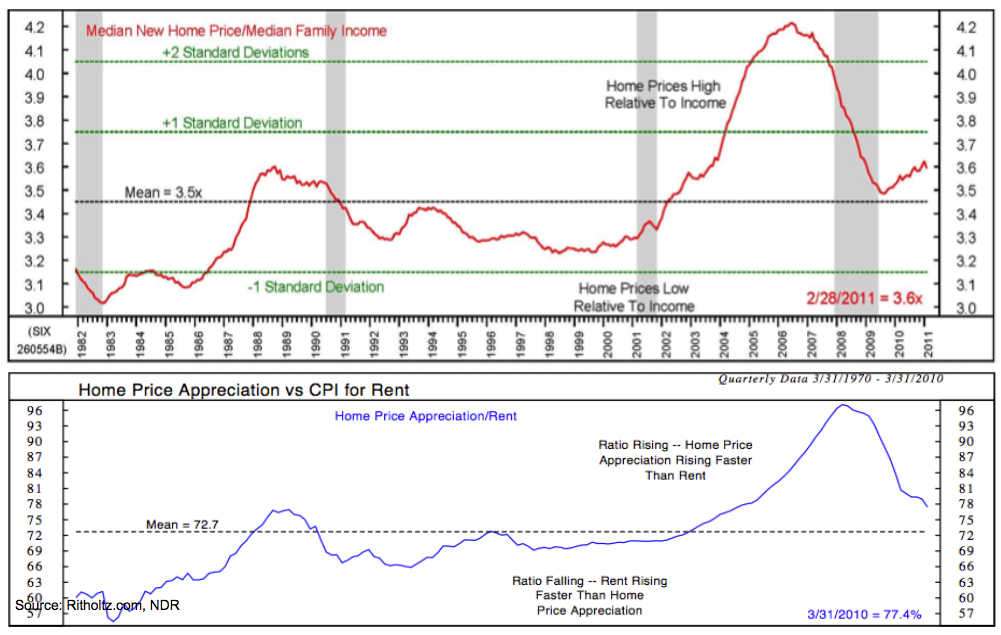

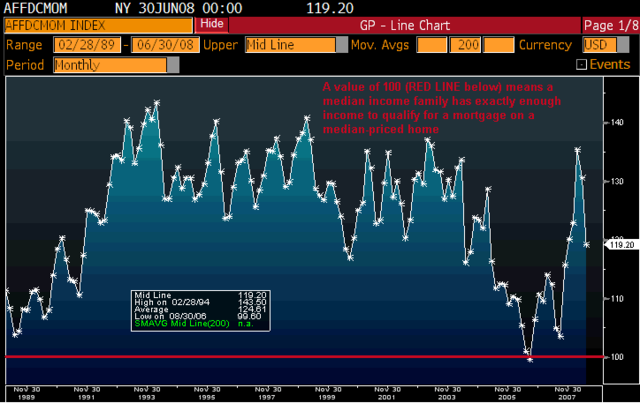

| Cheapest Homes in 40 Years? Not Even Close… Posted: 25 Apr 2011 04:23 AM PDT I have been wanting to discuss a horrifically misleading article for a week now: Americans Shun Cheapest Homes in 40 Years as Ownership Fades. It is an object lesson in how an industry spokesgroup, engaging in biased analysis, used poor econometric models to create misleading data. That led to others making bad assumptions based on that data, which in turn leads to an unsupported conclusions. To wit, that home prices are now cheap (they are not) and home ownership is being shunned (it is not). Thus, the end result is a misleading Bloomberg.com article on residential Real Estate that is unfortunately based on these terribly flawed NAR metrics. The reality is quite different than the spin. No, it is not, as objective data reveals, especially cheap. This flawed data/PR flack/spin approach is how the NAR manages to get a false and misleading claims printed in major US media on an all too regular basis. “The most affordable real estate in a generation” nonsense in Bloomberg is only the latest hoodwinking they have pulled on journalists. Recall back in 2009, the Wall Street Journal and IBD were both snookered by the NAR’s seasonal adjustments (we discussed this here, here, here, and here). Given the NAR’s track record when it comes to data analysis, anyone who makes any sort of purchase based on NAR spin is a fool who will get what they deserve. All of this leads to our present discussion of Home Affordability. Back in 2008, I wrote an analysis of the Realtors’ model titled “NAR Housing Affordability Index is Worthless.” As you can see from the chart below, during the entire boom period of 1996-2006, there was but ONE MONTH where the NAR index said homes were not affordable. Indeed, that chart period extends from 1985 to 2008 — there was but a single month of over-priced houses. How on earth did home prices NEVER become UNaffordable during the greatest run up in housing prices ever in the United States history? What sort of model refuses to allow homes to ever be perceived as unaffordable? We could only get that sort of thing from an industry source. Gee, do you think their bias impacts their index? Rather than rely on their silly, indefendable model, I suggest you compare median income to median home prices (see NDR chart below). That metric shows that homes are way off of their boom highs, but stilll remain somewhat overvalued relative to the buyers ability to pay for that home. If you were to measure affordability BUT ignore that metric (of ability to pay), what you will end up with is lots of new homeowners who cannot afford to pay for those homes. Which in turn leads to lots of foreclosures — which is exactly what has occurred here. By comparing Homes costs with buyers ability to pay for them, we can instead develop a sustainable model with periods of over and undervaluation — something the NAR model seems incapable of doing. That would render the NAR methodology, as a valuation measure, to be without any redeeming factors; (I believe the phrase I used in 2008 was “Worthless.”) I would argue the measure of Median income to Median home price a much better gauge. It tracks people’s ability to pay for homes — an important data point if you want to see a measure of affordability that also imagines not being foreclosed upon is a relevant part of affordability. Further, consider this perspective: How ownership ran up when money was free and lending standards had disappeared. That was obviously unsustainable. The latest home ownership data more likely reflects typical mean reversion to normalized ownership rates, rather than a paradigm shift in home ownership. At least, that is the my conclusion, relative to the ownership data and reversion to normal lending standards. Of all the media outlets to get suckered by a garbage datapoint, one would think Bloomberg would be the last. Perhaps its time for Bloomberg LLC to offer a refresher class on “Understanding data for Journalists” . . . > Median Incomes vs Median Home PricesNAR Affordability Index: Never Unaffordable> Previously: How to Read National Association of Realtors News Release (April 20th, 2011) Source: |

| He’ll talk about monetary policy but will he say US$? Posted: 25 Apr 2011 04:21 AM PDT The highlight of the week is going to be the Bernanke press conference after the release of their FOMC statement on Wed and while ears will be listening to his comments about the coming end of QE2 and what comes next, it will also be important if he discusses the state of the US$ or not. I say this for the obvious reason of the daily depreciation we see in its value and the coincident rise to new nominal new highs in gold and silver. He has punted on the issue in the past but has to acknowledge the impact of Fed policy and its impact on the value of the US$ as creating more dollars than there is demand for them is a devaluation. Let’s hope he doesn’t get softball questions. With European markets closed, the only other global action was in Asia and the Shanghai index closed at a 3 week low and the Yuan fell sharply as a Central Bank Advisor played down the talk last week of another one off revaluation of its peg to the US$. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

The Big Picture (ritholtz)

0 comments:

Post a Comment