The Big Picture |

- From Voodoo Economics to Pooh-Poohing Economics

- Save the Statistical Abstract

- The Fear Of Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

- Weak Bounce, No Follow Through

- World of Class Warfare

- Housing’s Big Chill

- Rosenberg’s 12 bullet points confirming double dip

- 30 Years Of Music Industry Change

- James Montier Suggested Reading List

- Forget TARP: Wall St Borrowed $1.2 Trillion from Fed

| From Voodoo Economics to Pooh-Poohing Economics Posted: 23 Aug 2011 02:00 AM PDT

~~~ It is said that any organization needs to understand and agree upon its problems, before it can develop solutions to them. The developed world, its inhabitants – and particularly its governments and political leadership – are having a devil of a time understanding (to say nothing of agreeing upon) the unprecedented set of economic facts that are facing us. Accordingly, the solutions proffered thus far have fallen far from being successful as we have been working at solving the wrong set of problems. Here are our real problems in a nutshell (a patient reader will find the solutions towards the end of this essay): The developed nations of Western Europe, the U.S. and Japan are facing the aftereffects of having for decades pursued policies, and tolerated private sector activity, that has been nearly the opposite of how they should have responded to the tectonic shifts in the structure of the global economy. We did not have a mere recession in 2007 and 2008, we experienced the beginning of the culmination of an era of ideologically-driven mismanagement occurring amidst, and partially in response to, one of the most massive changes in political economics in modern times. The fundamental catalyst was the emergence, and integration into the global free market, of nations that are home to the roughly 3.5 billion people formerly near-irrelevant to trade within the modern capitalist world – during the period prior to 1989 when they remained under the yoke of totalitarian "socialism" and other dysfunctional regimes. The word "emerging" to describe the newbie free market nations is, in itself, a bit euphemistic – this isn't some debutante ball we are talking about after all. Rather, something along the lines of "newly competing" or "status quo challenging" would be more apt. Don't get me wrong, I've got nothing against our new trading partners – I wish them well in the pursuit of economic growth and wellbeing for their people. But I have no delusions about what their "emergence" has meant to the hubristic developed world. The plain truth is that you cannot welcome 3.5 billion people (more than half of a world of 6.7 billion and a developed world numbering only about 660 million folks) into an already highly competitive global economy without rocking the boat – a lot. So much so that it threatens to capsize. But there we were, back in 1989, with our deregulated, laissez-faire, trickle-down, financialized economic philosophy of the Reagan-Bush era, the "voodoo economics" that thrives only by inducing debt fueled overconsumption. Like tent evangelists, we were preaching globalization to the world and giving each other high fives and belly bumps over the defeat of socialism by the Shining City upon a Hill. Back then, we were of course feeling the first failing of the economics of debt-dependent growth after the bubble of the 1980's (a response to the first round of deindustrialization – at that time generated by the Japanese). No matter though, that was our chance to show the world how to restructure from irrational exuberance and move on – and that we did. For a while, it felt good. We looked down at the Chinese with their political factions engaged in internecine struggles after Tiananmen. Had a good laugh about Yeltsin standing on a tank during the Moscow coup of 1991. And saw the India and Brazil as nations so hopelessly mired in unspeakable poverty that – a mere 20 years ago – to speak of them as dominant competitors would have had others questioning your sanity. Technology cut us a big break from 1995 through the very beginning of the new millennium. The impact of ever-faster, ever-smaller, computing and the revolution of internet technology not only brought us nearly seven years of ramped up productivity, government budget surpluses and strong domestic balance sheets (private and public), but it further united the world. If the advent of global news services such as CNN contributed towards bringing down isolationist regimes, then the internet certainly brought down the last remaining barrier to global, open trade: immediate communication. By the beginning of last decade the die was cast. We faced the most intense "supply shock" since the domestic over-investment that preceded the Great Depression – we didn't know it yet, but really should have foreseen it. After all, we woke up to the new century with (only) about $25 trillion of total debt outstanding in the U.S., and both household and government debt had diminished significantly. We were doing well. Incomes had risen in both nominal and real terms in the second half of the 1990's. Then, within months, we saw the collapse of the (not debt-fueled) internet bubble in the equity markets and 18 months later the horrors of September 11th. And what did we do? We fell right back under the spell of the supply-side voodoo we had suffered the ill results of only a decade before. Instead of tightening our belts in time of war, and reindustrializing at globally competitive wages, we went shopping on credit. A mere eight years later, we had more than doubled the level of total debt outstanding in the U.S. to more than $52 trillion and more or less impoverished our households/consumers. Wages stagnated while assets inflated. We consumed massively more than we were producing – a supply-side nightmare as we were beset by exogenous forces that hadn't even factored into the supply side equation. The asset inflation crashed back to earth, the debt remains and deleveraging is quite painful. America is an intellectually challenging place. So many people of so many different ethnicities, regional backgrounds and perspectives trying to coalesce around a common point of view, or even a plurality view. A substantial number not wanting to be bothered thinking at all beyond the immediate issues of family, friends, Facebook and financial survival. Reaching consensus on big issues in the U.S. has therefore never been easy – but I would daresay it hasn't been this challenged since the decades leading to the Civil War. Despite all the evidence to the contrary, there are still quite a few people – at all levels of influence – who believe we are in the process of recovering from a cyclical decline. We are not. We are, rather, fully experiencing the dislocations arising from the integration of the "status quo-challenging" nations. And up to this point, our policies have predominantly been targeted towards recovery from a conventional disruption in the business cycle – rather than what really ails us. Our leaders in academia and political economic thought are finally beginning to see things more clearly, and are beginning to offer solutions addressed to the right set of problems. Our private business sector has spent the last few years praying that what I am suggesting are the real problems, are not. But business leaders, for the most part, get it. They see it every day manifested in demand, relative pricing power and the ineffectiveness of policy that would typically help under different circumstances. They may put on a brave face, but their hiring, investment and pricing actions make clear their fears. The media is flummoxed. A good number of media people have long thought something was amiss, but they get paid to report on the zeitgeist not to make news. They are slowing beginning to write and speak the words that needed to be understood by their readers and audiences. Our political leaders, and the general population, are unfortunately still rather clueless. And it is only the political class, with the support of those who put them in office, who can turn the ship of government policy in a direction in which it might stand a chance at attacking the forces arrayed against our economic wellbeing – underemployment and over-indebtedness. Government leaders and the general population not only lack an appreciation of our problems, but lately have been pooh-poohing the entire study of economics in favor of mythic totems, such as small government, American exceptionalism and isolationism. There is a three part policy solution to what we face. Some of it is unpleasant, but all of it is necessary:

This challenge of global integration really amounts to waiting out the growth in emerging market demand to offset some of the excess supply. In the interim, we must do our part to generate demand – but, please, not through more household borrowing or over-stimulation of the private sector. We need to generate demand through higher aggregate income – and that means putting our people back to work via the only entity left to provide additional employment. ~~~ Dan Alpert is a founding Managing Partner of Westwood Capital. He has more than 30 years of international merchant banking and investment banking experience, including a wide variety of work-out and bankruptcy related restructuring experience. Dan's experience in providing financial advisory services and structured finance execution has extended Westwood's reach beyond the U.S. domestic corporate finance market to East Asia, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. In addition to his structured finance expertise, Dan has extensive experience advising on mergers, acquisitions and private equity financings. He has additional expertise in evaluating and maximizing the recoveries from failed financing vehicles affiliated with a common borrower/issuer. |

| Posted: 22 Aug 2011 04:54 PM PDT Via Paul Krugman, I’m led to this WaPo piece about the imminent demise of the Statistical Abstract of the United States, which is an invaluable resource for all manner of at-a-glance data. Regardless of one’s ideology or political leanings, I think we can all agree that more information is better, less information not as good, and the Abstract is a veritable treasure trove. This decision should not stand. A grassroots effort is needed here to petition the powers that be. Also, let them hear from you at the Census Bureau: ACSD.US.Data(AT)census.gov. Thanks. |

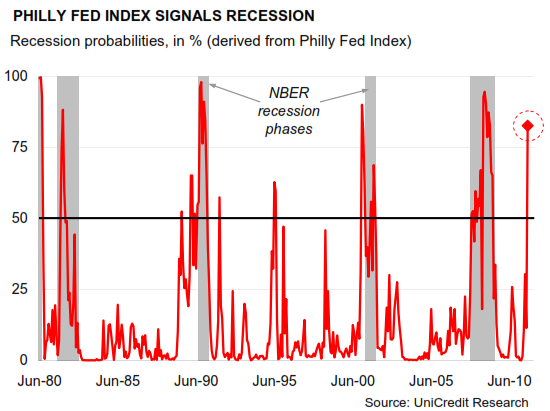

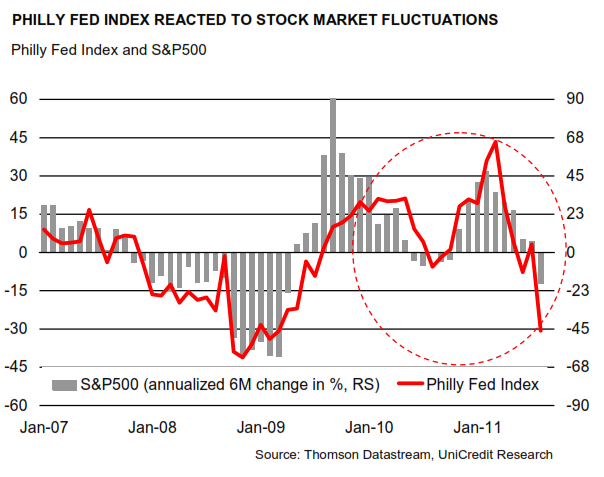

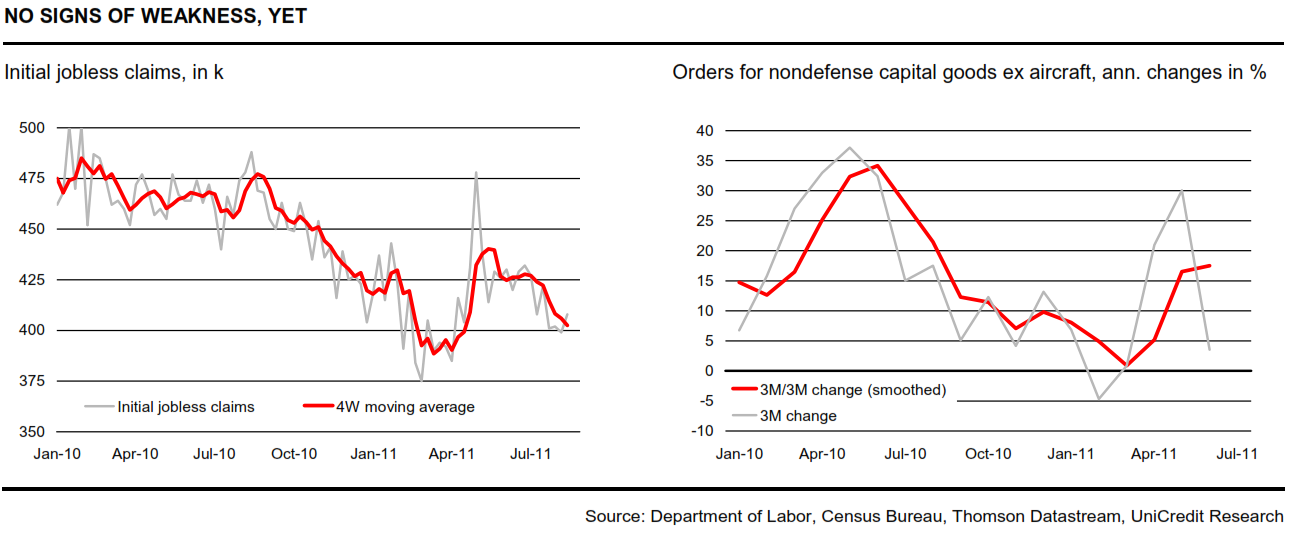

| The Fear Of Self-Fulfilling Prophecies Posted: 22 Aug 2011 03:00 PM PDT Harm Bandholz is the Chief US Economist for the UniCredit Group in New York. Before coming to the United States, Harm worked as an economist at HypoVereinsbank and as a Research Assistant at the Ifo Institute, both in Munich, Gemany. He holds a PhD in economics from the University of Hamburg and is a CFA Chartholder. Harm is also a member of the American Council on Germany and The Economic Club of New York. Philly Fed Index In Recession Territory The global economy is weakening. The only question for the coming months seems to be, how quickly growth will slow down and by how much? Yesterday's Philly Fed Index was undoubtedly grist to the mill of all those, who think that the recession in the US has already begun, or is about to start soon. The index, after all, plummeted to -30.7 in August from 3.2 in July. The monthly decline of 33.9 points was the sharpest drop since October 2008, i.e. the month after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. According to our calculations, the current index level translates into a recession probability of 82½% (see chart). It is interesting, though, that the Philadelphia Fed itself apparently tried to downplay the weakness of its own index, by emphasizing that "the collection period for this month's survey ran from August 8-16, overlapping a week of unusually high volatility in both domestic and international financial markets."1 Along the same lines, Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher told CNBC last night that while the Philly Fed Index is "a wonderful index" the stock market has in his view overreacted to the drop ("I think there’s a bit of an overreaction there.")2 We agree and think that the move should be taken with a pinch of salt. The latest hard numbers – initial jobless claims or weekly chain store sales – do, after all, not suggest at all that the economic situation between July and August deteriorated as much as between September and October 2008. Philly Fed Index gave no signals about the economic situation of late … In general it seems as if the formerly very tight correlation between the Philly Fed Index and measures of economic activity broke down in early 2010. While the Philly Fed Index has fluctuated widely over the last 1½ years, from +20 to -5, back to +40 and now down to -30, growth in manufacturing output was much more stable in this period(see left chart). The correlation with real GDP growth was even negative over the last four quarters (see right chart). Most notable: While the Philly Fed Index averaged a strong 30 points in the first quarter, real GDP eked out only a 0.4% increase. … but reacted to the stock market Fear of self-fulfilling prophecies Now, however, the stock market has of course reacted to the bad Philly Fed number as well (there is a certain irony that the stock market reacts to negative "news" that it somehow

Should the Fed target stock prices? 1 Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, August 2011 Business Outlook Survey. Source: |

| Weak Bounce, No Follow Through Posted: 22 Aug 2011 01:31 PM PDT It was a disappointing day for the Bulls. I came in today looking for an excuse to buy equities — and I never got it. As noted in the Smithers piece, markets may be due for bounce — he thinks due to buybacks, I think due to oversold conditions. The inability to maintain a strong opening, despite the deep discount from a month ago and the oversold condition makes me wonder if there isn’t more weakness to come. Bottom line: I did not see any reason to buy ‘em here yet. |

| Posted: 22 Aug 2011 01:17 PM PDT Warren Buffett vs. Wealthy Conservatives |

| Posted: 22 Aug 2011 11:30 AM PDT I always laugh whenever I hear anyone say eejit hack claim “No one saw it coming!” This video — featuring a thinner, less gray version of your humble blogger — discussing the coming housing storm in 2005 gives lie to that claim. The advice: Sell banks, Sell Home Builders, Sell Home Depot and Lowes. |

| Rosenberg’s 12 bullet points confirming double dip Posted: 22 Aug 2011 11:24 AM PDT The post below comes courtesy of Tyler Durden of the Zero Hedge blog . Funny how much can change in a month. After everyone was making fun of David Rosenberg as recently as June, not a single pundit who owns a suit and can therefore appear on CNBC dares to mention the original skeptic. Why? Because he has was proven correct (once again) beyond a reasonable doubt (and while we may disagree as to what asset class is best held into the terminal systemic collapse, Rosenberg has been one of the most steadfast and consistent predictors of the 'non-matrixed' reality in the world). Yet oddly enough there are still those who believe that a double dip (or, more accurately, a waterfall in the current great depressionary collapse accompanied by violent bear market rallies) is avoidable. Well, here, in 12 bullet points, is Rosie doing the closest we have seen him come to gloating … and proving the double dip or whatever you want to call it, is here. Bloomberg News has an article titled No Double Dip Yet With U.S. Economy Punching Up Growth Figures. Completely amazing, including the commentary from the economists in the article who seem to prefer forecasting based on coincident or lagging indicators. Because the data are subject to substantial revisions in the future, it is absolutely imperative that economic forecasters draw on their judgement and experience when making their predications (have a look at On Economy, Raw Data Get a Grain of Salt on the front page of today's NYT for case in point). Here is the reality.

And one final observation on GDP, which pretty much puts the double dip debate to rest: If you look at the monthly U.S. GDP data, it is already apparent that the U.S. economy is fraying at the edges. The economy contracted in both May and June and has shrunk now in four of the past six months. That sounds pretty recessionary to us. As the chart below shows, over the past six months, real GDP has actually declined at a 1.5% annual rate, which is just about as bad as it got at the worst point of the tech wreck a decade ago. Forewarned is forearmed. Source: Gluskin Sheff & Associates (via Zero Hedge), August 17, 2011. |

| 30 Years Of Music Industry Change Posted: 22 Aug 2011 11:00 AM PDT Via Digital Music News 30 Years Of Music Industry Change, In 30 Seconds Or Less… Each pie chart shows 1 year, from 1980-2010, based on RIAA revenue figures for the revenue contribution from various formats. >

US-based data of total recording revenue. And, here are the individual year source images, starting with 1980 on the top left and 2010 on the bottom right. Just pick a year and go, and download whatever you need. Hat tip Josh

~~~ |

| James Montier Suggested Reading List Posted: 22 Aug 2011 10:30 AM PDT Tim du Toit is the editor and founder of Eurosharelab. He has more than 20 year of institutional and personal investing experience in emerging and developed markets. Tim is based in Hamburg, Germany. More of his articles can be found at Eurosharelab (www.eurosharelab.com). Republished here with permission. ~~~ This article is the combination of two research reports I found where James recommended the best investment books he has come across. Be sure to read right to the end of the document to see the "hidden gems" James recommended. In order to give his choices a little structure James created four categories of books and only allowed him to select five books in each group. He admits that there were many great books that just didn't quite make his very restricted list. (click in the book picture or the bold text to go to the Amazon page) Classics The first category is the timeless masters. The books in this group have lasted for generations, yet their wisdom seems often to go unheeded. Security Analysis by Ben Graham and David Dodd

Some may prefer the easier (and more comfortable to hold) read that is provided by Graham's Intelligent Investor. Either or indeed both of these great books should be required reading for anyone serious about investing. Chapter 12 of the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money by John Maynard Keynes

However, Chapter 12 is very different from the rest of the book; it contains a wealth of understanding and analysis of the psychology and institutional constraints that bedevil investors as much today as they did when Keynes was writing in 1935. You can print it out for free at Project Gutenberg Australia The Theory of Investment Value by John Burr Williams

The book contains the essence of the discounted cash flow approach to valuation. As such it far predates the more widely cited Gordon papers (as in Gordon Growth Model). The book not only lays out the process and examples of DCF but also contains perhaps the first treatment of the industry lifecycle (Chapter VII). Williams opens The Theory of Investment Value with words that have been value investors' creed ever since "Separate and distinct things not to be confused, as every thoughtful investor knows, are real worth and market price." Manias, Panics and Crashes by Charles Kindelberger

This book contains not only a history of most of the major bubbles in financial markets, but also provides a framework for understanding their progress and ultimately their demise. As such it serves to remind us that although bubbles usually arise on different assets, the pattern they follow is relatively consistent. We have often used the Minsky/Kindelberger paradigm when discussing the path of bubble unwinding Reminiscences of a Stock Operator by Edwin Lefèvre

I've never forgotten that." Or "There is the plain fool, who does the wrong thing at all times everywhere, but there is the Wall Street fool, who thinks he must trade all the time. No man can always have adequate reasons for buying or selling stocks daily – or sufficient knowledge to make his play an intelligent play. I proved it." And "The desire for constant action irrespective of underlying conditions is responsible for many losses in Wall Street even among the professionals, who feel that they must take home some money every day, as though they were working for regular wages." But perhaps my favourite quotation is "A stock operator has to fight a lot of expensive enemies within himself." Modern To qualify to be in this section the book must have been written within the last ten years, but have the potential to become a classic given time. The little book that beats the market by Joel Greenblatt

In just 155 pages Greenblatt produces a mass of evidence showing that following a quantitative value orientated approach to stock selection can produce exceptional performance. But the book is more than just a quantitative take on the value process; it also contains gems such as "You must understand only two basic concepts. First, buying good companies at bargain prices makes sense… Second, it can take Mr. Market several years to recognize a bargain." Even better than that, the book is written so that an 11-year-old can understand it. But a lot of professional investors could do far worse than peruse this slim volume. The little book of value investing by Chris Browne

The very essence of the value approach and all it entails (patience etc.) are explored here in 180 pages. The discussion on the margin of safety highlights the way in which value investors think about risk – a far cry from modern portfolio theory's beta concept. Browne also explores issues such as how to distinguish a value trap from a value opportunity. Can be read easily in an afternoon, but should be repeatedly studied by value investors as a check on their own behaviour. Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Taleb

Every investor who has done well in a given period should read this book as a reality check, before they start to believe their own hype. Anyone who is vaguely interested in the role of luck, chance and randomness will find Taleb's book a source of much wisdom. Contrarian Investment Strategies by David Dreman

This tome is packed with deep insights into the nature of the investment problem, and practical investment strategies designed to avoid some of the behavioural pitfalls that we all too often stumble into. Dreman is also an empirical sceptic, and offers up good statistical evidence to support his analysis – something that is far too rare in the world of investment books. Speculative Contagion by Frank Martin Fo However, in the end I settled on Frank Martin's Speculative Contagion. This book pulls together the annual reports that Martin had written to his clients throughout the bubble and burst years. It is source of much investment insight. As regular readers will know James recently used Martin's trinity of risks as a basis of a better way of thinking about the nature of risk from an investment perspective. Martin's book provides us with opportunity to see exactly how bad it feels to be on the wrong side of a bubble, but also delivers insights into the discipline needed to stick to sensible investment process though thick and thin. Psychological James mentions that the books in this category are close to his heart. They are books on psychology. They aren't concerned with investing per se. Instead they are all concerned with the way in which we think and make choices. Investing is all about making decisions and choices, and as such I think a good grip on psychology is vital for all investor's hoping to conquer their internal demons. The Robots Rebellion by Keith Stanovich

At the heart of his approach is a dual system theory of thought (system X vs. system C for regular readers). The X system is very much a product of genetics, the C system provides us with a way of over-riding our genetic predispositions. Stanovich explores how evolutionary psychology and the heuristics and biases literatures can be reconciled (an arena that James has tried to explore before). The book also covers how and where many of the major biases are likely to show up. Strangers to Ourselves by Tim Wilson

Tim Wilson's book explores the modern concept of the unconscious (system X in many ways). He presents evidence showing that our actions are often outside of our conscious control. He also points out that simple introspection is not the answer, as we are more than capable of lying to ourselves. A brilliant, if disconcerting book. How we know what isn't so by Thomas Gilovich

Gilovich covers such areas as our misperception of random events (hot-hands in basketball), our habit of seeking out information that agrees with us (confirmatory bias), and issues surrounding group influence on decisions. Anyone interested in the pitfalls of human reasoning will find this a treasure trove of analysis. Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert

Gilbert is the leading expert in the field of affective (or emotional) forecasting. This book explores his research into why it is we don't make decisions that would make us happy. Gilbert argues that someone else's evaluation of how they feel in a given situation is a far better guide to how we will feel than our own prediction. Not only is Gilbert's subject fascinating, he is also an incredibly talented and funny writer, not to mention an astute observer of human behaviour with a wicked sense of humour. The Psychology of Intelligence Analysis by Richard Heuer, Jnr

He neatly reviews the psychology literature as it relates to the processing of information, and its application to solving intelligence problems. The overlap between intelligence analysis and investment analysis is surprisingly high. Both deal with decision making in the face of marked uncertainty. Heuer's book is an easy read that more than repays its reading. The chapter on the analysis of competing hypotheses should be mandatory reading for all financial analysts! This book may be the best value book on this list. Hidden Gems In this section James selected a hodgepodge of ideas and interesting reads, some are rare, some haven't even been published yet, but all provide some powerful insights into the investment problem. The Halo Effect by Phil Rosenzweig

Too many books in the business field go along the lines of Company "X" did exceptionally well for the last Y years, now study what they did and learn to apply it to your business. Or CEO of Company X created a culture of excellence, read this book and you can be like him. Even the so-called data based books like 'Good to Great' or 'In Search of Excellence' are really little more than stories masquerading as science. They are subject to the garbage in, garbage out critique, low quality data will result in low quality conclusions. My favourite section is on the halo effect – our habit of seeing one good trait and inferring lots of other good traits. It strikes me that analysts may often find themselves at the mercy of this effect – going and visiting a company, deciding they like the management and then inferring all sorts of desirable traits like future growth or cheapness. Mindless Eating by Brian Wansink

Exactly the same behavioural errors and mental pitfalls are displayed in the realm of food consumption and the financial markets. For those looking for an entertaining example of the wide spread nature of error prone human decision making this book is excellent. It also provides yet more evidence of the importance of codifying rules to help overcome our behavioural biases. The Inefficient Stock Market by Robert Haugen

His trilogy of books: The New Finance, The Inefficient Stock Market and the Beast on Wall Street are all excellent. But 'Inefficient' is my personal favourite. Haugen explores the failures of classical finance with his tongue firmly in his cheek. He also extols the virtues of multi-factor quantitative models, and his web site has plenty of data to show that the out of sample performance of such models has been exemplary. This book neatly combines theory and evidence – a top read. Margin of Safety by Seth Klarman

Klarman's discussions on the nature of value investing are priceless. As Klarman puts it "Value investing…is simply the process of determining the value underlying a security and then buying it at a considerable discount from that value. It is really that simple. The greatest challenge is maintaining the requisite patience and discipline to buy only when prices are attractive and to sell when they are not, avoiding the short-term performance frenzy that engulfs most market participants". James said that he displayed strong confirmatory bias when reading Klarman's work. Klarman argues that value investors should be absolute return focused, and that the margin of safety is all important and central to risk management. He also explores both the behavioural biases and institutional constraints that prevent most investors from following a value orientated strategy. Your Money and Your Brain by Jason Zweig

In this new book, Jason explores neuroeconomics as it applies to investing. The book is a pleasure to read – Jason's writing style is second to none. For those who are fascinated by the underlying neurological correlates of decision making, this is a must read. It also hints at why we find it quite so difficult to change our behaviour, many of the behavioural biases appear to be a hard wired function of brain architecture. In a June 2009 article James added a few titles to his reading list. Even before we know the outcome of the 2008 crisis, there has been an outpouring of books covering what went wrong and why. James chose three books to cover this genre, all by authors who can legitimately claim to have seen the crisis coming. Greenspan's Bubbles' by Bill Fleckenstein

It's a perfect antidote to the fawning 'Maestro' by Bob Woodward and the appalling 'Age of Turbulence' by Greenspan himself. Fleckenstein and his co-author, Frederick Sheehan, go back and expose exactly what Greenspan was saying at the time. They lay bare not only the former Fed chairman's complicity in the creation of bubbles (as if that wasn't bad enough), but also his cheerleading activities in bubble promotion. This is a short book that offers a damning indictment of the incompetence of the oft hallowed Greenspan Fed. More Mortgage Meltdown by Whitney Tilson and Glenn Tongue

The authors succeed in making the dry technicalities of mortgage malpractices lively and engaging. The crisis has left more than enough blame to go around. Tilson and Tongue do a good job of ensuring that the guilty parties are named and shamed – from the Fed to Wall Street and the ratings agencies, all the way to the government and homeowners themselves. The second part of the book walks readers through the analysis of six investment opportunities that are created by the crisis. Whether you agree with the authors' analysis or not (and generally I do) the real benefit of this section is the way it lays out the investment process that Tilson and Tongue follow, and shows how to follow this process using worked examples. The book reads easily, as those who know Whitney have come to expect. This is a great addition to any investor's library. Mr. Market Miscalculates by Jim Grant

His insights lay bare the fallacy of Greenspan's view that bubbles can't be analysed ex ante. Investment So on to the second topic – investment. These books aren't related to the current crisis but all provide deep insights into the nature of investing. Memos to Oaktree Clients by Howard Marks

This book isn't the easiest to track down (or indeed the cheapest at $200, available from Wave Publishing). The book collects together some of the best of Marks' writings from 1990 to 2005. The letters focus on Oaktree's investment philosophy and its application to the current investment juncture. Given that Oaktree is a fixed income outfit, the letters show how useful a value perspective can be in that market. The topics covered come close to my own heart such as the folly of forecasting, bubbles, the nature of risk and investment vs speculation. This is a collection that will have you returning on a regular basis to refresh your memory of Marks' words of wisdom. Distressed Investing by Marty Whitman and Fernando Diz

Who better to provide a guide through such a world than Marty Whitman (of Third Avenue fame). The authors walk the reader through the tricky pathways of reorganisation and bankruptcy. En route they chart the perils and pitfalls that can easily consume the unwary. They also elucidate on the nature of valuation and risk as it applies to distress investing. The book is written for US investors, so much of the focus is on 'going concern valuation' (Chapter 7 style), rather than liquidation. Despite the US focus, I think the book contains enough perspective to be worthy of an international audience.

Of course, technically Snowball isn't an investment book. It is a biography of Warren Buffett, but to me the two are intimately linked. Schroeder does an admirable job of portraying Buffett 'warts and all'. She documents the way in which Buffett built upon Ben Graham's ideas and extended (often in ways that Graham himself would probably have disapproved). But she goes further and provides us with a psychological profile which yields intriguing insights. For instance, Schroeder writes "he tended to extrapolate mathematical probabilities over time to the inevitable (and often correct) conclusion that if something can go wrong it eventually will." The Myth of the Rational Market by Justin Fox It is remarkable in the immediacy of its logical error and in the sweep and implications for its conclusion." Amen to that! Psychology The third category of books concerns James' own favourite subject area – Psychology. As Ben Graham long ago opined "The investor's chief problem and even his worse enemy is likely to be himself." The books in this section try to bring to life Graham's observation and in some cases explain how we might try to defend ourselves against ourselves. Animal Spirits by Robert Shiller and George Akerlof

They choose five psychological elements found at the heart of various economic conundrums –confidence, fairness, corruption and bad faith, money illusion and stories. They then go onto to explain how these five factors interact to help us understand some of the mysteries of economics, such as why do economies fall into depression, why does involuntary unemployment exist, and why are financial markets excessively volatile. In essence this book is a brave attempt to undo the separation of economics and psychology that occurred during the formalisation of the former. Some chapters hold together better than others, but ultimately the book serves as a powerful reminder that "left to their own devices, capitalist economies will pursue excess…There will be manias. The manias will be followed by panics". Think Twice by Michael Mauboussin

In his excellent new book, Michael takes the reader on a tour de force of behavioural decision errors. But he doesn’t stop there. Mauboussin also provides readers with concrete advice on how to avoid stumbling into some of the most common mental pitfalls. As one would expect from any book written by Michael, it reads exceptionally well, the pages almost turning themselves. As ever, James often measures a book by the number of pages he has marked or turned down. 'Think Twice' has more than its fair share. James mentioned that he I doesn't agree with everything in the book. Michael places far more importance on the "wisdom of crowds" than James does. But for anyone willing to seek wider insights into the nature of decision-making and how we can avoid stumbling into mental pitfalls, this book is a must read. Dance with Chance by Spyros Makridakis, Robin Hogarth and Anil Gaba

The answer is a book all about the 'illusion of control', which the authors define as trying to control what cannot be controlled, or to predict what cannot be predicted. In essence this is a book about the folly of forecasting – that's why James enjoyed it. The authors highlight the paradox of control. That is by giving up the pursuit of things we cannot control, we actually gain more control. This is similar to the point I have made before on the need to focus on the process rather than on the outcome. Freeing ourselves from endless worrying about things we can't control provides us with the ability to focus on the things we can. However, sometimes the book appears to offer poor advice. For instance, the authors seem to subscribe to the 'stocks for the long run' philosophy (buying stocks and holding them forever, regardless of valuation), which is anathema to James. However, if one can skip over these weaknesses, the book ultimately reminds me of Reinhold Neibuhr's serenity prayer: "God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference." Hidden gems The final group of books are what James calls hidden gems. These are books from outside the mainstream (by and large).

The ruling belief in Snow's time was that cholera was spread by bad air and bad smells. The book recounts the way in which John Snow and Henry Whitehead eventually traced the spread of disease to the water supply. The tale holds some powerful lessons for the way in which we should approach investment. Snow and Whitehead did their own work, they refused to be swayed by the popular beliefs of their time, and they continued to pursue the facts they uncovered until they reached the logical conclusion. Contrarians rejoice. The final two choices are more personal to James than any other books on his lists. In the past James has occasionally referred to Winnie the Pooh as a source of much underestimated investment advice. His Bloomberg header is a quotation from Pooh, "Never underestimate the value of doing nothing." James mentions that he is also a fan of eastern philosophy. These may seem like non-sequiturs, but both are brought together in one of this year's hidden gems A Gift to My Children by Jim Rogers

However, his favourite advice is this: "The basic principle to remember is this: They need you more than you need them… Don't follow a boy to a different school, city, or job. Make the boys follow you". The Tao of Pooh and the Te of Piglet by Benjamin Hoff

I have long felt that investors could learn much from such an approach. |

| Forget TARP: Wall St Borrowed $1.2 Trillion from Fed Posted: 22 Aug 2011 08:30 AM PDT > I continue to be of the mind that the Wall Street Bailouts were misguided, and that a massive Swedish style reorg would have been the best thing for the nation and the economy in the long run. Both Uncle Sam and the Fed would have provided the broad based debtor in possession financing required, and the losses would have fallen where they belonged — on the Shareholders and Bond Holders — and not the taxpayers. The latest evidence of this: Data obtained by Bloomberg News through Freedom of Information Act requests, followed by months of litigation, and eventually, an act of Congress. (Wall Street Aristocracy Got $1.2T in Loans) And the data ain’t pretty. We knew that Citigroup (C), who borrowed $99.5 billion, and Bank of America (BAC), who took loans of $91.4 billion, were in trouble. I’ve been saying for the better part of 3 years now that they were, and likely still are mostly insolvent. But the surprise data point was Morgan Stanley (MS), got as much as $107.3 billion in loans, with no strings attached. What should have happened? Imagine if the government and the Federal Reserve were run not by knaves and fools and Wall Street sycophants, but instead, were run honestly for the benefit of the taxpaying voter. Imagine the goal was saving the banking system (not the banks), and the financial rescue was for the benefit of the taxpayers, not the bondholders. Naive thoughts, I totally understand, but hear me out. A person who truly understood what had happened and why would have considered the following actions. Note these are not ideas come about with the benefit of hindsight, but what a small band of insightful people were saying at the time. An honest broker of the situation would have:

Instead, we bailed out the bondholders and management, choking off hope for a robust recovery. We are in fact slowly turning Japanese, awaiting the next recession (and the next and the next). > Source: Previously: |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment