The Big Picture |

- Jackson Hole

- A Pseudorandom Walk Down Wall Street

- Succinct Summation Of Week’s Events (08/26/11)

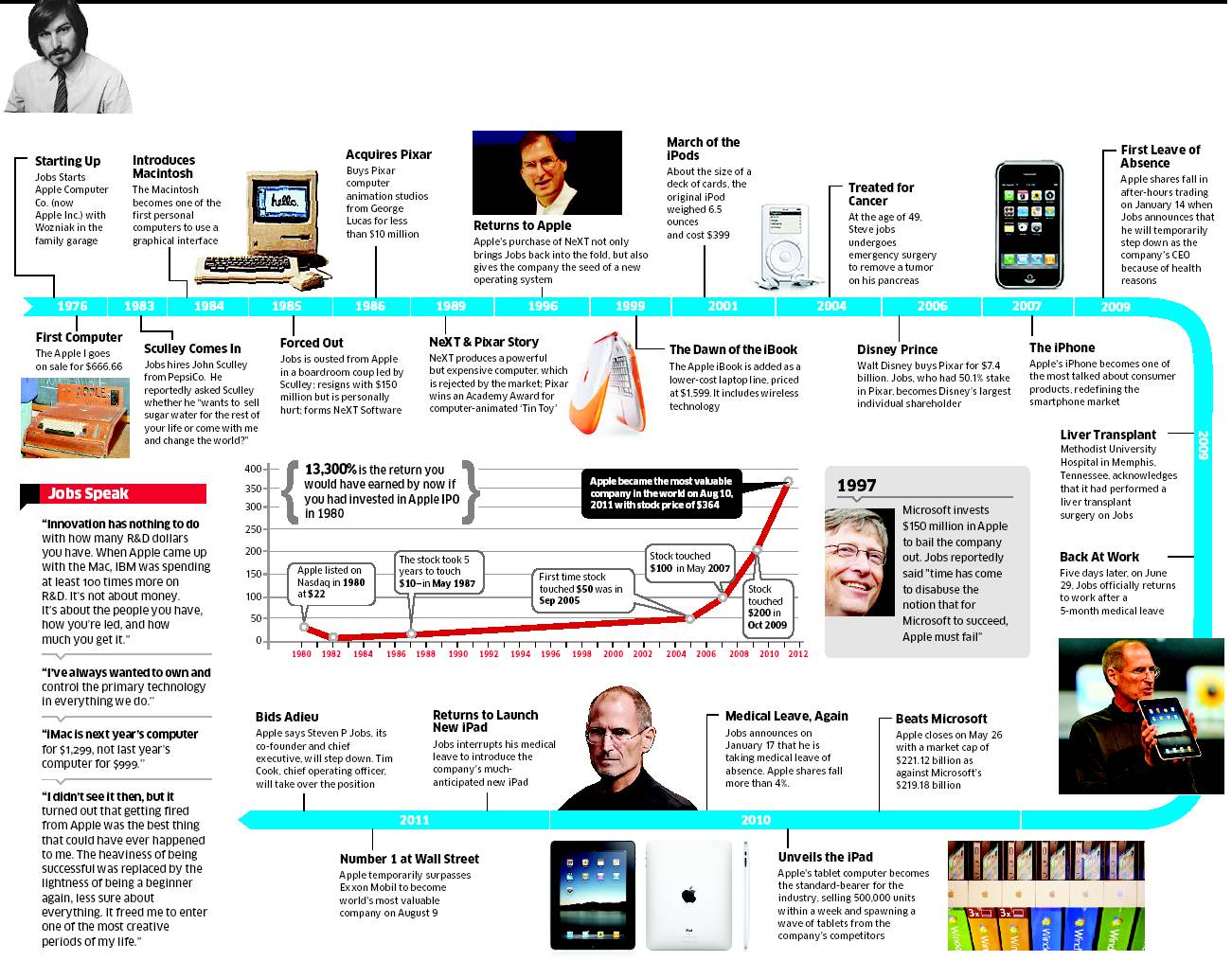

- Steve Jobs Life In Charts

- 1934 Voisin C-25 Aerodyne wins Best of Show at 2011 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance

- Academic paper questions HFT role in volatility and correlation

- The Heart of the Matter

- Koo Says U.S. Economy Is Following Japan’s Pattern

- Bernanke as expected but addicts always want more

- Chairman Ben S. Bernanke: The Near- and Longer-Term Prospects for the U.S. Economy

| Posted: 26 Aug 2011 08:54 PM PDT Jackson Hole ~~~ Markets dipped when Chairman Bernanke failed in his Jackson Hole speech to deliver the hoped-for elixir of QE3, then rallied as attention turned to other issues like Hurricane Irene. But market expectations were unrealistic and motivated by self-interested desire for a positive jolt to equities, rather than a realistic assessment of Federal Reserve policy or what should or should not be done in the interest of the country. Consistent with the theme of the Jackson Hole conference, which focused on longer-term growth issues facing the economy, Chairman Bernanke described the present state of the economy, current policy, and what the Fed and rest of the government could and couldn't do to promote expansion and growth. He indicated that while the "hoped-for" pickup in the economy the FOMC expected earlier in the year had failed to materialize, the economy was still expanding; and over the longer run he did not believe that growth fundamentals had been seriously compromised by the shocks the economy had experienced during and after the financial crisis. Indeed, he said, the most likely scenario would be slow growth and a gradual recovery. There were, however, several important parts of the speech that provided a realistic and objective assessment of why the recovery has been slow to materialize. Bernanke made it clear that he believed monetary policy was supportive of expansion, but he correctly pointed out that the Fed could not create jobs or clean up the dismal housing situation. He bluntly suggested that the recent budget and debt-ceiling debacle damaged consumer and business confidence and posed a downside risk. In the short run the burden was on Congress and the Administration to craft proactive fiscal policies to deal with the jobs issues and to clean up the excess supply of housing that were holding back the expansion. Perhaps the most important part of the speech, however, was his observation that the quality of economic policy making would significantly impact the nation's longer-run growth prospects. He implied that changes were needed; and he made concrete, broad-based suggestions for how to deal with the country's fiscal and budget issues. In particular, he laid out what amounted to a two-stage process for getting the government's financial spiral, which was driven by our aging population and rising health-care costs, under control. The first task should be to put in place a credible plan for bringing expenditures and revenues into balance, establishing a more effective process for setting budget goals and ensuring they are carried out. The second step would be the difficult process of balancing the hard tradeoffs among competing choices that a credible budget process would require. This step would also require Congress to make sure that the public not only understood and bought into the budget control plan but also accepted the tradeoffs that had to be made to meet the plan's goals. Chairman Bernanke has clearly and correctly put his finger on the budget issues, how fiscal policy choices would determine the longer-term growth prospects for the economy, and what is needed to address those problems. The responsibility belongs to Congress, and time is short to put our house in order. ~~~

|

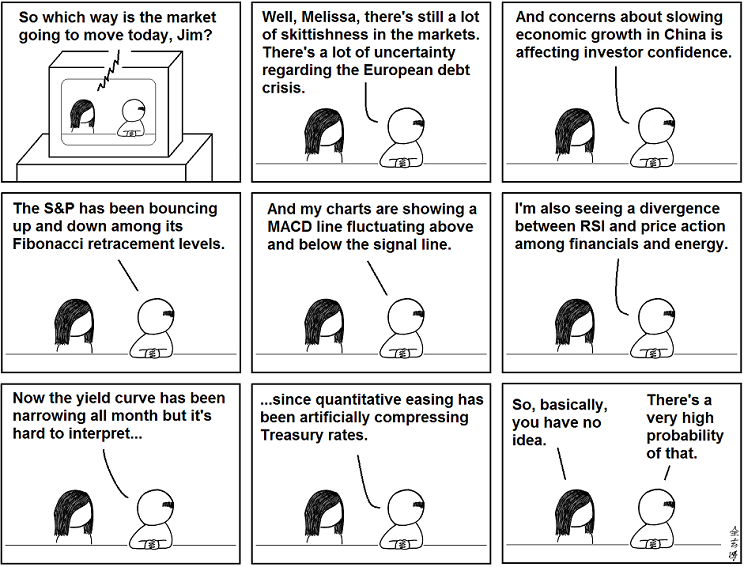

| A Pseudorandom Walk Down Wall Street Posted: 26 Aug 2011 04:24 PM PDT |

| Succinct Summation Of Week’s Events (08/26/11) Posted: 26 Aug 2011 12:30 PM PDT Succinct summation of week’s events: Positives:

Negatives:

|

| Posted: 26 Aug 2011 11:00 AM PDT Source: |

| 1934 Voisin C-25 Aerodyne wins Best of Show at 2011 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance Posted: 26 Aug 2011 10:42 AM PDT |

| Academic paper questions HFT role in volatility and correlation Posted: 26 Aug 2011 09:00 AM PDT Joseph Saluzzi (jsaluzzi-at-ThemisTrading.com) and Sal L. Arnuk (sarnuk-at-ThemisTrading.com) are co-heads of the equity trading desk at Themis Trading LLC (www.themistrading.com), an independent, no conflict agency brokerage firm specializing in trading listed and OTC equities for institutions. Prior to founding Themis, Sal and Joe worked for more than 10 years at Instinet Corporation, pioneers in the field of electronic trading, and at Morgan Stanley. ~~~ Chances are that if you went to business school or even just took some business courses as an undergraduate, you probably forked over a few bucks for a Frank Fabozzi textbook. Professor Fabozzi has written many books on finance and is highly respected in the academic community. To our surprise, we recently came across a paper titled "High Frequency Trading:Methodologies and Market Impact" (Read Paper Here) which was co-authored by Professor Fabozzi. We must admit that the first thought that came to mind was that the HFT lobby has pulled another Mishkin and gotten an academic to write a paper for them. Before even reading these types of papers, we first always check the references section to see what type of work the author will be referencing. Here is where our anxiety level started to climb. In the reference section, we saw names like Aldridge, Angel, Brogaard and Hendershott. Missing from the reference section was anything published by Arnuk and Saluzzi or Kaufman or R.T. Leuchtkafer. We were thinking now that this paper had all the makings of a pro-HFT hit piece. Here is a line from the conclusion of the paper: "Empirical analysis has shown that the presence of HFTers has improved market quality in terms of lowering the cost of trading, adding liquidity, and reducing the bid-ask spreads." Oh boy, not the old it shrinks spreads and adds liquidity argument again. But wait a second, the next line goes on to say: "Given the short-time nature of HFT and the fact that positions are typically not carried overnight, the potential for market manipulation and for the creation of bubbles and other nefarious market effects seems to be modest." Did he just say "modest"? The typical HFT hit piece would say that market manipulation is not possible and there is no nefarious behavior and say HFT is just market making evolved. We read on: "The problems posed by HFT are more of the domain of model or system breakdown or cascading (typically downward) price movements as HFTers withdraw liquidity from the markets." Whoa..this can't be an academic paper. It is actually questioning whether or not HFT withdraws liquidity from the market. Why haven't we read any articles that have quoted from this paper? Maybe the HFT community and their enablers were hoping we didn't see this paper. The paper is actually a well balance report which sometimes argues in favor but also questions many HFT practices. The beginning section talks about what the authors refer to as HFD or high frequency data and UHFD or ultra high-frequency data. They state: "HFD and UHFD might be considered the fuel of HFT." In other words, without the exchange supplied highly enriched private data feeds, there would be no HFT. The latter section of the paper goes into the pros and cons of HFT. The authors quote from a few different professors and reveal some startling quotes that we haven't seen before: Professor Voev: "There is recent evidence that HFT is leading to more correlation, a fact that has serious implications for diversification. This is making it more difficult to diversify with index tracking or exchange-traded funds. There are now thousands of algos trading indexes, moving prices. Is price momentum dominated by traders trading indexes?" Professor Bauwens: "My conjecture is that HFT has in most cases increased the speed at at which prices adjust to reflect new information; thus, it has led to increased efficiency. However, it has also been noted that correlation between intraday returns of stocks has increased without apparently much reason, and this may be caused by HFT driven by econometric models disconnected from fundamentals." Professor Voev: "We now have faster channels of market fear, uncertainty. Is HFT causing this or is it just a question of faster channels, with HFT facilitating fast channeling of emotions, fear? In normal times, HFT brings smoother adjustment to new levels versus discrete moves which are more volatile. But in more extreme circumstances, it can lead to spikes in volatility." There is much more in this paper than we can't cover in this blog post. If you get a chance, give it a read. And the good thing is you don't have to pay for Fabozzi for the textbook |

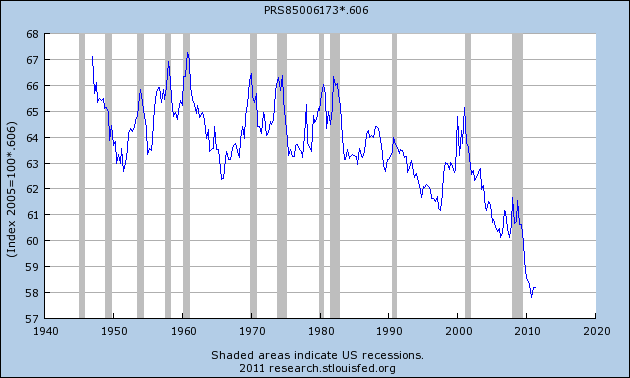

| Posted: 26 Aug 2011 08:30 AM PDT Some of the factors that have landed us in the mess we’re in have been building for decades, and there’s ample evidence on which to draw to demonstrate that fact. In looking at a few of these issues, I’ll draw on some charts I’ve presented both here and elsewhere before. A couple are replicated from this outstanding study in January’s Monthly Labor Review (MLR). Let’s begin by referencing a recent piece by Stephen Roach that accurately assesses what’s really wrong with our current economy, summed up in one number:

Here’s a graphic representation of what Mr. Roach is talking about: We’ve gone, 14 quarters from the start of the recession, from an index value of 100 to a current index value of 100.7, which is an average annualized growth rate of 0.2 percent. Anemic. Given that consumer spending represents some 70 percent of GDP, a wobbly consumer — note the flatline over the past two quarters — is problematic. And at the risk of turning blue in the face, I’d point out yet again that we know small businesses cite “Poor Sales” as their number one single biggest problem. So, to the extent very little (anything?) has been done to help the consumer, the mess in which we find ourselves should come as absolutely no surprise. Corporations, which are flush with cash, are spending that cash on such things as mergers, acquisitions, share buybacks, and dividend hikes. While that’s all well and good for the investor class, it does virtually nothing for Joe Six Pack on Main St. That said, let’s peel the onion a bit and look at factors that are behind the our weak consumer. First up, Labor Share, which the MLR defines as:

Here’s what has become of Labor Share: (NOTE: BLS provides (and FRED captures) this series as an Index, not a Level, with 2005 = 100. BLS advises me that the 2005 Level = 60.6. Therefore, I have taken the entire Index (Series identified above) and multiplied it by .606 to get the percent Labor Share above. It continues to bewilder me that more is not made of this troubling metric.) As the MLR points out:

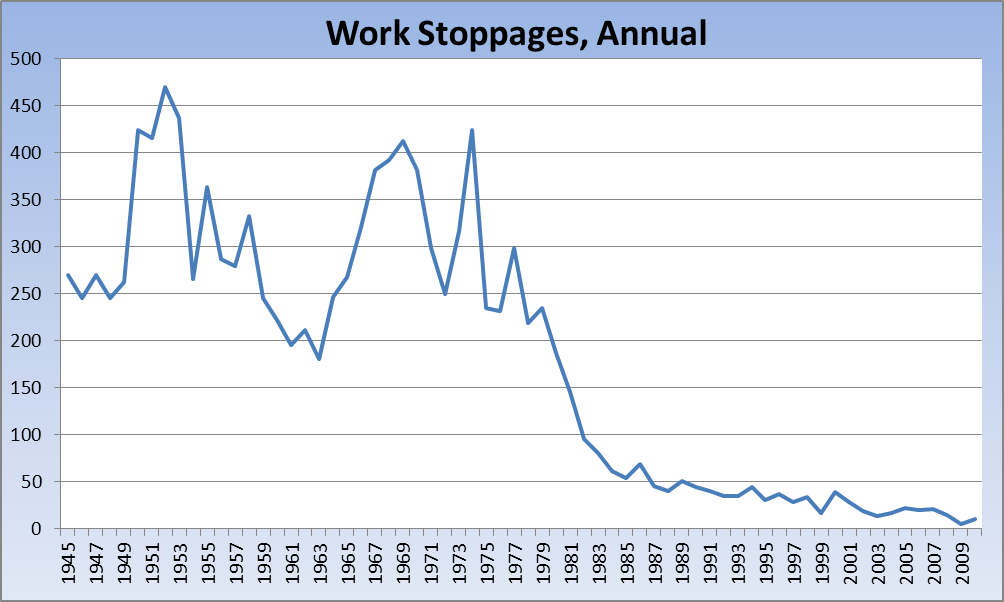

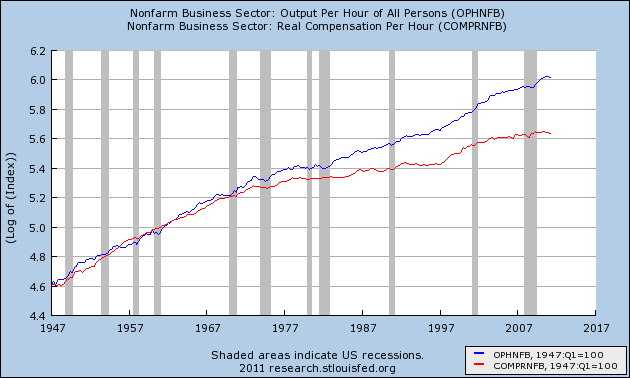

The decline in Labor Share can also be looked at in the context of the growing impotence of unions in the United States, as well as declining union membership (for which I could not find an adequate chart). Here is a chart showing the number of work stoppages annually since 1947: While Labor Share has recently plummeted to all-time lows since record keeping began, Median Household Income has stagnated for the past 12 years. In the last recession (2001), incomes had only begun to decline. I’m sure back then no one contemplated the possibility that the decline would last (certainly not for a decade), credit was still widely available and, as we know now, being freely tapped (see the PCE chart above for evidence of how normal consumer spending remained during that period). One decade later, Labor Share has collapsed, incomes have gone nowhere, and credit availability — to say nothing of consumers’ attitudes toward it — has all but vanished except for the most creditworthy. To add insult to injury, Output — or Productivity — has far outstripped Compensation since ’70s, no doubt due in very large part to advances in technology. The gap is even wider in the manufacturing sector of the economy (see Chart 6 in the MLR study). Producing more for less and with less has become a hallmark of good corporate management at the expense, of course, of the American worker. It is a lynchpin of the great American mantra of “maximizing shareholder value.” The chart below is a natural log chart (which should please the readers who have occasionally suggested the use of log charts) in which both metrics were indexed to 100 at the earliest measurement . There may — operative word “may” — be a glimmer of hope on the horizon for consumers, though I think it’s fair to say the administration’s previous forays into the housing market have been generally ineffective. I’ll outsource some commentary and number crunching to David Rosenberg:

I’d hasten to point out that there are doubts about the plan over at Calculated Risk. We are now squarely face-to-face with the consequences of the decades long gutting of the middle class that was the backbone of our economy for so long. Without taking some solid, clearly-defined steps, the middle class will undoubtedly move from an endangered species to extinction. The tipping point may already have been passed and, even if it hasn’t, I’m still not optimistic there’s any interest in D.C. to make the requisite policy changes. On a somewhat related note as Irene barrels up the eastern seaboard and warnings of widespread power outages are sent far and wide, I can’t help but wonder (yet again) why no consideration is ever given to burying our power lines in the northeast. Is it too common sense, too potentially stimulative, too money-saving in the long run, or all three? |

| Koo Says U.S. Economy Is Following Japan’s Pattern Posted: 26 Aug 2011 08:00 AM PDT Richard Koo, chief economist at Nomura Research Institute, talks about the outlook for the U.S. economy and Federal Reserve policy and the American BALANCE SHEET RECESSION:

|

| Bernanke as expected but addicts always want more Posted: 26 Aug 2011 07:15 AM PDT Bernanke is talking about the challenges the US economy faces, why the recovery has been lackluster but keeps his optimistic view that the future still looks bright. He also reviewed the Aug 9th FOMC meeting and gave some color on the policy change announced that day. He also reiterated (said also on Aug 9th) that the Fed “has a range of tools that could be used to provide additional monetary stimulus…We will continue to consider those and other pertinent issues” at the next few FOMC meetings. He goes on to defend the role of monetary policy in fostering economic growth (in his opinion) but also notes its limits. He then cited iscal policy as needing to help out. He finished the speech with, while “economic policymakers face a range of difficult decisions…I have no doubt that those challenges can be met and that the fundamental strengths of our economy will ultimately reassert themselves. The Fed will certainly do all that it can to help restore high rates of growth and employment in a context of price stability.” Bottom line, this speech should be as expected as the Fed is at the end of its line with policy but Bernanke doesn’t want to fully admit it yet. The markets reaction is to be expected because of the dependency that last yr created but it should also not be surprised by what was said today. |

| Chairman Ben S. Bernanke: The Near- and Longer-Term Prospects for the U.S. Economy Posted: 26 Aug 2011 07:00 AM PDT Chairman Ben S. Bernanke The Near- and Longer-Term Prospects for the U.S. Economy Good morning. As always, thanks are due to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City for organizing this conference. This year’s topic, long-term economic growth, is indeed pertinent–as has so often been the case at this symposium in past years. In particular, the financial crisis and the subsequent slow recovery have caused some to question whether the United States, notwithstanding its long-term record of vigorous economic growth, might not now be facing a prolonged period of stagnation, regardless of its public policy choices. Might not the very slow pace of economic expansion of the past few years, not only in the United States but also in a number of other advanced economies, morph into something far more long-lasting? I can certainly appreciate these concerns and am fully aware of the challenges that we face in restoring economic and financial conditions conducive to healthy growth, some of which I will comment on today. With respect to longer-run prospects, however, my own view is more optimistic. As I will discuss, although important problems certainly exist, the growth fundamentals of the United States do not appear to have been permanently altered by the shocks of the past four years. It may take some time, but we can reasonably expect to see a return to growth rates and employment levels consistent with those underlying fundamentals. In the interim, however, the challenges for U.S. economic policymakers are twofold: first, to help our economy further recover from the crisis and the ensuing recession, and second, to do so in a way that will allow the economy to realize its longer-term growth potential. Economic policies should be evaluated in light of both of those objectives. This morning I will offer some thoughts on why the pace of recovery in the United States has, for the most part, proved disappointing thus far, and I will discuss the Federal Reserve’s policy response. I will then turn briefly to the longer-term prospects of our economy and the need for our country’s economic policies to be effective from both a shorter-term and longer-term perspective. Near-Term Prospects for the Economy and Policy We meet here today almost exactly three years since the beginning of the most intense phase of the financial crisis and a bit more than two years since the National Bureau of Economic Research’s date for the start of the economic recovery. Where do we stand? There have been some positive developments over the past few years, particularly when considered in the light of economic prospects as viewed at the depth of the crisis. Overall, the global economy has seen significant growth, led by the emerging-market economies. In the United States, a cyclical recovery, though a modest one by historical standards, is in its ninth quarter. In the financial sphere, the U.S. banking system is generally much healthier now, with banks holding substantially more capital. Credit availability from banks has improved, though it remains tight in categories–such as small business lending–in which the balance sheets of potential borrowers remain impaired. Companies with access to the public bond markets have had no difficulty obtaining credit on favorable terms. Importantly, structural reform is moving forward in the financial sector, with ambitious domestic and international efforts underway to enhance the capital and liquidity of banks, especially the most systemically important banks; to improve risk management and transparency; to strengthen market infrastructure; and to introduce a more systemic, or macroprudential, approach to financial regulation and supervision. In the broader economy, manufacturing production in the United States has risen nearly 15 percent since its trough, driven substantially by growth in exports. Indeed, the U.S. trade deficit has been notably lower recently than it was before the crisis, reflecting in part the improved competitiveness of U.S. goods and services. Business investment in equipment and software has continued to expand, and productivity gains in some industries have been impressive, though new data have reduced estimates of overall productivity improvement in recent years. Households also have made some progress in repairing their balance sheets–saving more, borrowing less, and reducing their burdens of interest payments and debt. Commodity prices have come off their highs, which will reduce the cost pressures facing businesses and help increase household purchasing power. Notwithstanding these more positive developments, however, it is clear that the recovery from the crisis has been much less robust than we had hoped. From the latest comprehensive revisions to the national accounts as well as the most recent estimates of growth in the first half of this year, we have learned that the recession was even deeper and the recovery even weaker than we had thought; indeed, aggregate output in the United States still has not returned to the level that it attained before the crisis. Importantly, economic growth has for the most part been at rates insufficient to achieve sustained reductions in unemployment, which has recently been fluctuating a bit above 9 percent. Temporary factors, including the effects of the run-up in commodity prices on consumer and business budgets and the effect of the Japanese disaster on global supply chains and production, were part of the reason for the weak performance of the economy in the first half of 2011; accordingly, growth in the second half looks likely to improve as their influence recedes. However, the incoming data suggest that other, more persistent factors also have been at work. Why has the recovery from the crisis been so slow and erratic? Historically, recessions have typically sowed the seeds of their own recoveries as reduced spending on investment, housing, and consumer durables generates pent-up demand. As the business cycle bottoms out and confidence returns, this pent-up demand, often augmented by the effects of stimulative monetary and fiscal policies, is met through increased production and hiring. Increased production in turn boosts business revenues and household incomes and provides further impetus to business and household spending. Improving income prospects and balance sheets also make households and businesses more creditworthy, and financial institutions become more willing to lend. Normally, these developments create a virtuous circle of rising incomes and profits, more supportive financial and credit conditions, and lower uncertainty, allowing the process of recovery to develop momentum. These restorative forces are at work today, and they will continue to promote recovery over time. Unfortunately, the recession, besides being extraordinarily severe as well as global in scope, was also unusual in being associated with both a very deep slump in the housing market and a historic financial crisis. These two features of the downturn, individually and in combination, have acted to slow the natural recovery process. Notably, the housing sector has been a significant driver of recovery from most recessions in the United States since World War II, but this time–with an overhang of distressed and foreclosed properties, tight credit conditions for builders and potential homebuyers, and ongoing concerns by both potential borrowers and lenders about continued house price declines–the rate of new home construction has remained at less than one-third of its pre-crisis level. The low level of construction has implications not only for builders but for providers of a wide range of goods and services related to housing and homebuilding. Moreover, even as tight credit for some borrowers has been one of the factors restraining housing recovery, the weakness of the housing sector has in turn had adverse effects on financial markets and on the flow of credit. For example, the sharp declines in house prices in some areas have left many homeowners “underwater” on their mortgages, creating financial hardship for households and, through their effects on rates of mortgage delinquency and default, stress for financial institutions as well. Financial pressures on financial institutions and households have contributed, in turn, to greater caution in the extension of credit and to slower growth in consumer spending. I have already noted the central role of the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 in sparking the recession. As I also noted, a great deal has been done and is being done to address the causes and effects of the crisis, including a substantial program of financial reform, and conditions in the U.S. banking system and financial markets have improved significantly overall. Nevertheless, financial stress has been and continues to be a significant drag on the recovery, both here and abroad. Bouts of sharp volatility and risk aversion in markets have recently re-emerged in reaction to concerns about both European sovereign debts and developments related to the U.S. fiscal situation, including the recent downgrade of the U.S. long-term credit rating by one of the major rating agencies and the controversy concerning the raising of the U.S. federal debt ceiling. It is difficult to judge by how much these developments have affected economic activity thus far, but there seems little doubt that they have hurt household and business confidence and that they pose ongoing risks to growth. The Federal Reserve continues to monitor developments in financial markets and institutions closely and is in frequent contact with policymakers in Europe and elsewhere. Monetary policy must be responsive to changes in the economy and, in particular, to the outlook for growth and inflation. As I mentioned earlier, the recent data have indicated that economic growth during the first half of this year was considerably slower than the Federal Open Market Committee had been expecting, and that temporary factors can account for only a portion of the economic weakness that we have observed. Consequently, although we expect a moderate recovery to continue and indeed to strengthen over time, the Committee has marked down its outlook for the likely pace of growth over coming quarters. With commodity prices and other import prices moderating and with longer-term inflation expectations remaining stable, we expect inflation to settle, over coming quarters, at levels at or below the rate of 2 percent, or a bit less, that most Committee participants view as being consistent with our dual mandate. In light of its current outlook, the Committee recently decided to provide more specific forward guidance about its expectations for the future path of the federal funds rate. In particular, in the statement following our meeting earlier this month, we indicated that economic conditions–including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run–are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through mid-2013. That is, in what the Committee judges to be the most likely scenarios for resource utilization and inflation in the medium term, the target for the federal funds rate would be held at its current low levels for at least two more years. In addition to refining our forward guidance, the Federal Reserve has a range of tools that could be used to provide additional monetary stimulus. We discussed the relative merits and costs of such tools at our August meeting. We will continue to consider those and other pertinent issues, including of course economic and financial developments, at our meeting in September, which has been scheduled for two days (the 20th and the 21st) instead of one to allow a fuller discussion. The Committee will continue to assess the economic outlook in light of incoming information and is prepared to employ its tools as appropriate to promote a stronger economic recovery in a context of price stability. Economic Policy and Longer-Term Growth in the United States Notwithstanding the severe difficulties we currently face, I do not expect the long-run growth potential of the U.S. economy to be materially affected by the crisis and the recession if–and I stress if–our country takes the necessary steps to secure that outcome. Over the medium term, housing activity will stabilize and begin to grow again, if for no other reason than that ongoing population growth and household formation will ultimately demand it. Good, proactive housing policies could help speed that process. Financial markets and institutions have already made considerable progress toward normalization, and I anticipate that the financial sector will continue to adapt to ongoing reforms while still performing its vital intermediation functions. Households will continue to strengthen their balance sheets, a process that will be sped up considerably if the recovery accelerates but that will move forward in any case. Businesses will continue to invest in new capital, adopt new technologies, and build on the productivity gains of the past several years. I have confidence that our European colleagues fully appreciate what is at stake in the difficult issues they are now confronting and that, over time, they will take all necessary and appropriate steps to address those issues effectively and comprehensively. This economic healing will take a while, and there may be setbacks along the way. Moreover, we will need to remain alert to risks to the recovery, including financial risks. However, with one possible exception on which I will elaborate in a moment, the healing process should not leave major scars. Notwithstanding the trauma of the crisis and the recession, the U.S. economy remains the largest in the world, with a highly diverse mix of industries and a degree of international competitiveness that, if anything, has improved in recent years. Our economy retains its traditional advantages of a strong market orientation, a robust entrepreneurial culture, and flexible capital and labor markets. And our country remains a technological leader, with many of the world’s leading research universities and the highest spending on research and development of any nation. Of course, the United States faces many growth challenges. Our population is aging, like those of many other advanced economies, and our society will have to adapt over time to an older workforce. Our K-12 educational system, despite considerable strengths, poorly serves a substantial portion of our population. The costs of health care in the United States are the highest in the world, without fully commensurate results in terms of health outcomes. But all of these long-term issues were well known before the crisis; efforts to address these problems have been ongoing, and these efforts will continue and, I hope, intensify. The quality of economic policymaking in the United States will heavily influence the nation’s longer-term prospects. To allow the economy to grow at its full potential, policymakers must work to promote macroeconomic and financial stability; adopt effective tax, trade, and regulatory policies; foster the development of a skilled workforce; encourage productive investment, both private and public; and provide appropriate support for research and development and for the adoption of new technologies. The Federal Reserve has a role in promoting the longer-term performance of the economy. Most importantly, monetary policy that ensures that inflation remains low and stable over time contributes to long-run macroeconomic and financial stability. Low and stable inflation improves the functioning of markets, making them more effective at allocating resources; and it allows households and businesses to plan for the future without having to be unduly concerned with unpredictable movements in the general level of prices. The Federal Reserve also fosters macroeconomic and financial stability in its role as a financial regulator, a monitor of overall financial stability, and a liquidity provider of last resort. Normally, monetary or fiscal policies aimed primarily at promoting a faster pace of economic recovery in the near term would not be expected to significantly affect the longer-term performance of the economy. However, current circumstances may be an exception to that standard view–the exception to which I alluded earlier. Our economy is suffering today from an extraordinarily high level of long-term unemployment, with nearly half of the unemployed having been out of work for more than six months. Under these unusual circumstances, policies that promote a stronger recovery in the near term may serve longer-term objectives as well. In the short term, putting people back to work reduces the hardships inflicted by difficult economic times and helps ensure that our economy is producing at its full potential rather than leaving productive resources fallow. In the longer term, minimizing the duration of unemployment supports a healthy economy by avoiding some of the erosion of skills and loss of attachment to the labor force that is often associated with long-term unemployment. Notwithstanding this observation, which adds urgency to the need to achieve a cyclical recovery in employment, most of the economic policies that support robust economic growth in the long run are outside the province of the central bank. We have heard a great deal lately about federal fiscal policy in the United States, so I will close with some thoughts on that topic, focusing on the role of fiscal policy in promoting stability and growth. To achieve economic and financial stability, U.S. fiscal policy must be placed on a sustainable path that ensures that debt relative to national income is at least stable or, preferably, declining over time. As I have emphasized on previous occasions, without significant policy changes, the finances of the federal government will inevitably spiral out of control, risking severe economic and financial damage.1 The increasing fiscal burden that will be associated with the aging of the population and the ongoing rise in the costs of health care make prompt and decisive action in this area all the more critical. Although the issue of fiscal sustainability must urgently be addressed, fiscal policymakers should not, as a consequence, disregard the fragility of the current economic recovery. Fortunately, the two goals of achieving fiscal sustainability–which is the result of responsible policies set in place for the longer term–and avoiding the creation of fiscal headwinds for the current recovery are not incompatible. Acting now to put in place a credible plan for reducing future deficits over the longer term, while being attentive to the implications of fiscal choices for the recovery in the near term, can help serve both objectives. Fiscal policymakers can also promote stronger economic performance through the design of tax policies and spending programs. To the fullest extent possible, our nation’s tax and spending policies should increase incentives to work and to save, encourage investments in the skills of our workforce, stimulate private capital formation, promote research and development, and provide necessary public infrastructure. We cannot expect our economy to grow its way out of our fiscal imbalances, but a more productive economy will ease the tradeoffs that we face. Finally, and perhaps most challenging, the country would be well served by a better process for making fiscal decisions. The negotiations that took place over the summer disrupted financial markets and probably the economy as well, and similar events in the future could, over time, seriously jeopardize the willingness of investors around the world to hold U.S. financial assets or to make direct investments in job-creating U.S. businesses. Although details would have to be negotiated, fiscal policymakers could consider developing a more effective process that sets clear and transparent budget goals, together with budget mechanisms to establish the credibility of those goals. Of course, formal budget goals and mechanisms do not replace the need for fiscal policymakers to make the difficult choices that are needed to put the country’s fiscal house in order, which means that public understanding of and support for the goals of fiscal policy are crucial. Economic policymakers face a range of difficult decisions, relating to both the short-run and long-run challenges we face. I have no doubt, however, that those challenges can be met, and that the fundamental strengths of our economy will ultimately reassert themselves. The Federal Reserve will certainly do all that it can to help restore high rates of growth and employment in a context of price stability. 1. See Ben S. Bernanke (2011), “Fiscal Sustainability,” speech delivered at the Annual Conference of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Washington, June 14. Return to text |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment