The Big Picture |

- Can Your Tablet Save the Planet

- The History and Rationale for a Separate Bank Resolution Process

- Thursday Night Open Thread

- FusionIQ’s Ritholtz on Facebook IPO, U.S. Economy

- 10 Thursday PM Reads

- American Gridlock

- Five Long-Term Unemployment Questions

- Fox News vs Amsterdam

- 10 Thursday Mid-Day Reads

- Facebook IPO by the Numbers

| Can Your Tablet Save the Planet Posted: 03 Feb 2012 01:30 AM PST |

| The History and Rationale for a Separate Bank Resolution Process Posted: 02 Feb 2012 10:30 PM PST The History and Rationale for a Separate Bank Resolution Process > Everyone recognizes the need to have a credible resolution regime in place for financial companies whose failure could harm the entire financial system, but people disagree about which regime is best. The emergence of the parallel banking system has led policymakers to reconsider the dividing line between firms that should be resolved in bankruptcy and firms that should be subject to a special resolution regime. A look at the history of insolvency resolution in this country suggests that a blended approach is worth considering. Activities that have potential systemic impact might be best handled administratively, while all other claims could be dealt with under a court-supervised resolution. Lehman Brothers' filing of a petition to reorganize under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code in September 2008 was a watershed event in the recent financial crisis. The ensuing market turmoil led to heated debate about whether bankruptcy is an appropriate mechanism for resolving the insolvency of a systemic financial company. On one side of this debate are those who believe that with some adjustments the judicial process of bankruptcy is a viable option for handling the failures of most types of financial firms. On the other side are proponents of an administrative process akin to that used to resolve insured depository institutions. In one sense, the Dodd–Frank Consumer Protection and Wall Street Reform Act of 2010 settled this debate. Notable among its reforms is the Orderly Liquidation Authority, a process for resolving systemic nonbank financial companies that parallels a Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) bank receivership. In another sense, Dodd–Frank has fueled further debate: It has made orderly liquidation an exceptional power by mandating that financial companies create and maintain plans for resolution under the Bankruptcy Code; it has also ordered studies of possible reforms to the Code that would allow for more orderly resolution of systemic financial companies through bankruptcy. Government policy for resolving insolvent financial institutions is at a crossroads. There is little dispute about the importance of designing and implementing a credible resolution regime for systemic financial companies. However, there is considerable debate about the best method for doing so. When deciding between bankruptcy and an FDIC-like administrative process to resolve nonbank financial companies, it is natural to ask why bank failures were ever handled differently. Today, there seems to be general agreement that banks' payments-related functions (from issuing bank notes and taking checkable deposits to clearing and settling payments) require special treatment, but it was not always so. This Commentary seeks to inform the debate by examining how resolution policies for failed banks evolved in U.S. history. Bank Resolutions in the Pre-Bankruptcy EraThe United States did not enact a permanent federal bankruptcy code until the end of the nineteenth century. Although there had been many attempts to enact such a code, these were either defeated in Congress or, if enacted, were soon repealed. Hence, for much of U.S. history, banking and commerce operated in a world without any federal bankruptcy code. For corporations, including banks, resolution had to take place by other means. Before enacting the National Currency Act of 1863 and the National Banking Act of 1964 ("the Acts"), the federal government was not in the business of chartering banks (the First and Second Banks of the United States being notable exceptions). Banks were state-chartered corporations, subject to oversight by the state in which they operated; most were designed to self-liquidate when their charters expired, generally after 20 years. However, banks were different from other corporations in one particularly important way: they issued bank notes, which were an important part of the nation's money supply. Deposit-taking was another vital activity of banks during this era, but failure to redeem bank notes was the primary driver of failed-bank resolution policies.

For state-chartered banks, the resolution process usually entailed a determination of insolvency whose main criterion was the bank's ability to redeem its notes in a timely fashion.1 Failure to do so would result in the state redeeming the bank's notes and then asking a state court to revoke the bank's charter, forcing it to shut down operations. If the court determined that the bank was insolvent, a receiver would be appointed by either the court or the banking commissioner. Over time, states began to adopt balance-sheet insolvency as a separate criterion for closing a bank, but the resolution process remained largely unchanged. With the exception of banking law's focus on issuing and redeeming notes, banks' insolvency resolution process was not all that different from that of other corporations. In most cases, they were identical: Before New York pioneered a special bank-insolvency regime, some states used the same resolution mechanism for all corporations. Even after New York enacted its law, failed banks were resolved like any other corporation, except that note redemption provisions applied to them. This would change in one important way, however, when the federal government began chartering banks at the height of the Civil War. The establishment of a national bank system and a uniform national currency gave rise to the first noteworthy distinction between banks and nonbank corporations in the process of insolvency resolution. National banks would be chartered by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, a subagency of the U.S. Treasury and as such, it is unclear whether states had the power to resolve them. The absence of federal insolvency law meant that the Acts needed to provide a process for winding up the affairs of national banks that were forcibly closed or voluntarily shuttered their operations. As we noted earlier, a primary objective for establishing the national banking system was to create a uniform national currency. This required that national bank notes be uniformly backed by eligible U.S. government bonds and that there be a seamless process for redeeming and retiring the notes of failed banks. National banks that could not redeem their notes in a timely way would have their charters revoked by the Comptroller of the Currency and be subject to an administrative receivership process. The focus on note redemption as a solvency test and the use of a receivership to resolve bank failures mirror the resolution process for state-chartered banks. Somewhat paradoxically, in 1867, three years after the federal bank resolution mechanism went into effect, a federal bankruptcy law that applied to banks was passed. Although the 1867 Bankruptcy Act does not explicitly discriminate between state and national banks, subsequent court rulings would determine that it did not apply to national banks. Though it lasted only a few years before being repealed, the federal mechanism for bankruptcy resolution established in the 1867 Act required court oversight and was used to resolve a number of state-chartered banks. Unlike its state-chartered counterpart, a national bank's closure would receive no judicial oversight under the '63 and '64 Acts. It would be 35 years after the establishment of the national banking system before the nation would have a permanent bankruptcy code. By that time, over half of the states had bank insolvency regimes in place. Congress would exclude banks from the bankruptcy code because mechanisms were already in place at both the state and federal levels:

Insurance companies, railroads, and any other companies for which a well-established, state-level resolution mechanism was in place were also excluded from bankruptcy. New Deal ReformsOn the heels of massive bank failures, the Banking Act of 1933 established a system of federal deposit guarantees and created a new entity, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The FDIC would be charged with insuring depositors' bank accounts and would (for national banks and most state-chartered banks) operate and administer the receivership of failed banks; this was expanded in the late 1980s to include all FDIC-insured depository institutions. By protecting depositors, federal deposit guarantees would prevent runs and provide for the stability of the payments system because demand deposits had become an increasingly important part of the narrow money supply—that is, money held largely for transactions purposes—the equivalent of M1 (coin and currency, checkable deposits, and travelers checks) today. Bank notes were not a concern in Depression-era banking legislation because Federal Reserve notes had largely replaced them as payment instruments. In 1934, the first year of the FDIC's operations, national bank notes made up only 17 percent of all currency in circulation, 4 percent of the narrow money stock, and only around 2 percent of bank liabilities. Demand deposits, on the other hand, accounted for 79 percent of the narrow money stock and more than 65 percent of the liabilities of FDIC-insured commercial banks. At this time, there were two noteworthy changes in the bank resolution process. First, the receivership's focus shifted from redeeming notes to minimizing the costs of the failure for the deposit insurance fund. The second change was the placement of bank receivership authority in the FDIC, the largest creditor of an insured bank's estate. While out of step with practice under bankruptcy law, this novel arrangement would be consistent with the objective of bank resolution policy—that is, minimizing the losses to depositors and the FDIC when a bank failed. Depression-era banking reforms were not enacted in a vacuum. As the banking bills were being debated in Congress, legislative attention was also directed towards revamping the Bankruptcy Code. Years of debate culminated in the Chandler Act of 1938, which continued to exclude banks, savings and loans, and insurance companies. This is not surprising, perhaps, when one considers that the financial reforms of the 1930s sought to segregate banking from other financial activities. Further embedding the closing and resolution of insolvent banks as regulatory functions by placing bank receivership under the FDIC is consistent with the 1930s banking reforms aimed at partitioning the financial system. Relatively Recent Developments in Bank Resolution PolicyOver time, with periodic guidance from Congress, the judicial system of bankruptcy and the administrative process of bank resolution evolved as separate regimes, with differing objectives. Reorganizing and preserving a firm's value remain the centerpiece of the Bankruptcy Code for corporations. Ironically, although bank insolvency law and bankruptcy have remained separate resolution regimes, financial innovation, coupled with legislative and regulatory reform, has increasingly blurred the distinction between banks and nonbank financial companies. As a result, a firm's organizational form, not the types of activities or functions it undertakes, would be the determining factor in whether bankruptcy law or bank insolvency law would apply when it failed. Probably the most dramatic changes in the objectives of bank insolvency resolution were responses to the regional banking and savings and loan debacles of the 1980s. Policies governing the closing and resolution of insolvent banking companies became increasingly driven by the political economy of bank supervisory policy. The rescue of the Continental Illinois Bank and Trust Company of Chicago in 1984 marked the first time insolvency resolution policy would be driven by concerns of systemic risk—the birth of the unofficial policy known as the too-big-to-fail doctrine. In response to the banking and thrift problems of the 1980s, Congress enacted several pieces of legislation, culminating in the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991. This legislation encompassed reforms in the bank supervisory infrastructure, including the powers and objectives of the bank-insolvency-resolution authority. The goal of minimizing a bank failure's cost to the deposit insurance fund was replaced by the least-cost resolution mandate, which directed supervisors to minimize total costs, not just those to the FDIC fund. In addition, to limit systemic spillovers, lawmakers added prompt corrective action to the objectives of the bank resolution regime and an exemption to the least-cost rule (the systemic risk exemption). Most recently, in the wake of the rise and fall of the shadow banking system, Congress took a step toward broader use of the administrative bank resolution process to resolve large systemic financial companies. Title II of the Dodd–Frank Consumer Protection and Wall Street Reform Act of 2010 added the Orderly Liquidation Authority to the FDIC's set of receivership powers (see Fitzpatrick and Thomson, 2011). Although the Authority was meant to be an extraordinary power, it was another step toward broader use of the administrative bank-insolvency resolution process in an increasing set of nontraditional bank activities. Policy ImplicationsIn recent history, banks have been treated differently from other firms, even other financial firms. The banking industry has long had its own set of supervisory agencies as well as a separate process for closing and winding up insolvent banks. Maintaining the integrity of the payments system required a predictable set of procedures for handling the insolvency of banking companies. The absence of a permanent bankruptcy code in the United States, which persisted until the end of the nineteenth century, necessarily led to development of a bank-specific insolvency resolution system for banks. Congress has chosen to keep bank insolvency resolution within the bank regulatory system, distinct and separate from bankruptcy. The emergence of "parallel" or "shadow" banks has led policymakers to reconsider the dividing line between firms that should be resolved in bankruptcy and those that should be subject to a special resolution regime. Understanding what unique features of a depository institution make bankruptcy an unsatisfactory option for insolvency resolution is important for understanding what reforms to the Bankruptcy Code are needed to effectively resolve insolvent nonbank financial companies—or whether bankruptcy can be a satisfactory option for insolvency resolution for some types of firms. Banking history suggests that payments-related activities and functions are where such an inquiry should start. Finally, the history of bank insolvency law and bankruptcy law suggests a careful reconsideration of whether the choice of an insolvency resolution regime should be made at the firm level or the activity level. One reasonable lesson from the history of insolvency resolution is that we should consider a blended approach—in which only the truly systemic activities of a bank or nonbank financial firm are handled administratively and all other claims are dealt with under a court-supervised resolution. Footnotes

Recommended Readings "Resolving Insolvent Large Complex Financial Institutions: A Better Way," by Robert R. Bliss and George G. Kaufman, 2011. The Banking Law Journal, 128:4, 339–63. "Resolving Large, Complex Financial Firms," by Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV, Mark B. Greenlee, and James B. Thomson, 2011. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary, 2011–16. "How Well Does Bankruptcy Work when Large Financial Firms Fail? Some Lessons from Lehman Brothers," by Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV and James B. Thomson, 2011. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary, 2011–23. "An End to Too Big to Let Fail? The Dodd–Frank Act's Orderly Liquidation Authority," by Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV and James B. Thomson, 2011. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary, 2011–1. "Bank Receivership and Conservatorship," by Walker F. Todd, 1994. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary. ~~~ About the author: Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV is an economist in the Community Development Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. His primary fields of interest are housing finance, particularly residential mortgage backed securitizations, loss-mitigation strategies, and the remediation of vacant and abandoned real property. He is also interested in financial regulation, consumer finance, and community development. Mr. Fitzpatrick is a member of the Ohio Bar Association and licensed to practice law in Ohio. |

| Posted: 02 Feb 2012 05:00 PM PST Hey, its been a while — hat say we open up the floor for any and all topics? What’s on your collective minds? What is interesting/curious/provocative/entertaining — no subject off limits. Emerging markets? Dividends? More bond rally? Trump endorsed Who? What say ye? |

| FusionIQ’s Ritholtz on Facebook IPO, U.S. Economy Posted: 02 Feb 2012 01:55 PM PST Barry Ritholtz, chief executive officer at FusionIQ, talks about Facebook Inc.’s initial public offering and U.S. weekly jobless claims. Ritholtz speaks with Betty Liu and Dominic Chu on Bloomberg Television’s “In the Loop.” Feb. 2 (Bloomberg) - |

| Posted: 02 Feb 2012 01:30 PM PST My afternoon train reading:

What are you reading? > |

| Posted: 02 Feb 2012 12:00 PM PST American Gridlock How do we resolve the current political gridlock over healthcare, the economy, and a myriad of other problems? It is clear that there are no easy solutions, and putting off making choices will just make the ultimate cost we pay that much more expensive. This week for our Outside the Box we deal with just this question, in a piece from a master of logic and reasoning and one of my favorite writers. I absorb everything I can get my hands on from Dr. Woody Brock. He has written a new book, called American Gridlock: Why the Left and Right are Both Wrong” (www.amazon.com/gridlock). I am doing something very unusual and giving him two back-to-back editions of Outside the Box, this week and next, to outline his own book in his own words. He generously agreed to do so, as he (and I) are passionate about the topic of getting to a solution. If we do not solve this crisis in the making, it will impair our future generations for a long time, not to mention its effects on our own lives. I should note to my non-US readers that the principles in this book extrapolate to situations outside our borders, and I suggest you too read this OTB carefully. Gridlock is not just an American phenomenon, but a result of the changing of the way we process information in the age of Big Data. From this piece: “Regrettably, what has happened in recent years is that ‘pure’ inductive logic has been replaced by that bastardized form of data analysis all too familiar from today’s Dialogue of the Deaf: As time goes on, each side cherry-picks ever more data to strengthen their prejudiced positions. Thus, positions become ever more shrill. Belief modification and dialectical progress are rarely achieved. In this sense, giving young research associates Excel spreadsheets plus the wealth of information accessible from the internet is proving very dangerous to informed debate. ‘Factoids’ are confused with serious logic, and young people are all but clueless about Hume’s imperative: You cannot data-crunch your way to the Truth. Ever.” I know some of you will disagree with Woody on certain things, but your disagreement will probably be with his basic assumptions, not his reasoning thereafter. What he is talking about is akin to some things I studied way back in the day, but that have fallen from fashion – as Woody points out. Coincidentally, Woody will be here in Dallas tomorrow night and Wednesday, and we will break bread (and other culinary delights) at Stephan Pyles’ fabulous namesake establishment with Rich Yamarone, and then attend the CFA Forecast Dinner here in Dallas on Wednesday. You can learn more about Woody and his economic services at www.SEDinc.com, as well as see some of his previous essays. Enjoy your week; I know I am going to enjoy mine. Your thinking about First Principles analyst, John Mauldin, Editor American GridlockWhy The “Left” And The “Right” Are Both WrongCommonsense 101 Solutions to the Economic CrisesDr. Woody Brock Pessimism is ubiquitous throughout the Western World as the pressing issues of massive debt, high unemployment, and anemic economic growth divide the populace into warring political camps. Right- and Left-wing ideologues talk past each other, with neither side admitting the other has any good ideas, and with no effort expended to seek higher-order policy solutions that entirely transcend the arguments of both the Right and the Left. My new book American Gridlock is an optimist’s antidote to this state of affairs, and to today’s pessimism. I attempt not only to bridge, but in fact to transcend today’s Left/Right divide and arrive at win-win solutions to a host of policy dilemmas confronting the nation. These solutions illuminate a clear path out of today’s economic quagmire, a path leading to a much brighter future. The celebrated economist Nouriel Roubini has aptly summarized the thrust of this new book: With rigorous logic, American Gridlock identifies five major problems confronting the nation. These range from salvaging today’s “Lost Decade,” to the unequal distribution of wealth, to preventing bankruptcy from future “entitlements” spending, and to preventing future financial market crises. Woody Brock does not simply offer his opinions about these crises. Rather, he deduces his win-win solutions to each of these from First Principles. It is high time for such a book, especially during an election year. In this first of a two-part description of the book’s themes, I shall discuss the first three of six chapters. The three topics are: (1) How to terminate today’s deafening Dialogue of the Deaf between our two political parties — that embarrassing shouting match between Left and Right that has generated gridlock; (2) How to revivify the US economy today, and spare us a so-called Lost Decade; and (3) How to rein in entitlements spending without reducing social services needed by millions of Americans — medical services in particular. In a sequel to this essay next week, I shall confront three other policy challenges: How to prevent future Financial Perfect Storms of the kind that brought the world down in 2008; How not to bargain with China as we have for decades, with the US ending up on the losing side of most negotiations despite possessing about four times the “net power” of China measured correctly within game theory; and finally, What exactly is an “idealized” resource allocation system? By what criteria can we legitimately rank communism versus socialism versus capitalism versus whatever? And more fundamentally, what exactly do we mean when we speak of “fair shares” of income and wealth? This last topic is my favorite. Amongst other issues, it requires us to make a distinction between true Adam Smith capitalism versus that bastardized form of capitalism so visible today — where K Street has replaced the Invisible Hand of perfect competition with the Visible Fist of money and corruption. Additionally, when we confront the thorny issue of “fair shares,” I shall sketch a new theory of social justice that integrates the two fundamental strands of the theory of Distributive Justice: Distribution in accord with workers’ Relative Contributions, versus distribution in accord with citizen’s Relative Needs. In any satisfactory theory of justice, both these moral norms must find a proper place. What is perhaps most novel about American Gridlock is the way in which solutions to the various policy problems are arrived at, a point stressed by Roubini: I utilize deductive logic (deductions from First Principles), as opposed to inductive logic (inferences often derived from ideologically-driven data analysis). New and powerful forms of deductive logic are introduced throughout the book, as and when needed. These include game theory, a new theory of “optimal” government deficits, the economics of uncertainty, new extensions of the Law of Supply and Demand, and modern moral theory. The new perspectives these theories make possible become the levers and pulleys that permit the discovery of new win-win policy solutions that transcend today’s Left/Right divide, and in so doing help break up policy gridlock.

It is important to understand this point up front, for the over-arching goal of the book is to demonstrate the existence of new win-win policies that can neutralize gridlock in Washington. While some of these new theories will be unfamiliar to many readers of the book, they are introduced in a very relaxed manner, and no mathematics is required. Believe me, no publisher keen to sell books will allow an equation to be seen! To me, these fascinating new theories are all part of the syllabus of the new course I hope to develop when I retire: Commonsense 101. Chapter 1: Today’s Dialogue of the Deaf – And How to End ItIn this first chapter, I set the stage for what follows. First, it is shown how the Dialogue of the Deaf is one (but not the only) source of policy gridlock. In Washington, matters have reached the unprecedented point whereby Republican and Democratic congressmen no longer eat at the same restaurants. The news media are characterized by the familiar Left/Right back-and-forth between the New York Times on the Left, and the Wall Street Journal on the Right, between MSNBC on the left, and Fox News on the right. Those classical courses in rhetoric and in debating which inculcated the Socratic Dialogue as a mode of reasoning and discourse have disappeared, and we are now treated to brain-dead shouting matches between warring camps. Recall that in the Socratic Dialogues of Plato, argument proceeded from initial definitions and assumptions to compelling conclusions arrived at jointly by all those engaged in debate. There is a reasoning process that leads from proposition A to B, B to C, and ultimately to the conclusion Z. Many steps of logic are required as the debate unfolds. In many cases, everyone agrees with the conclusion Z, if and when it is reached. Participants agree because they have been part of the process of preceding from A to Z. Contrast this with today’s shouting match between the Left and Right. There is no reasoned dialectic. There are only recycled sound bites that the public increasingly tunes out. Both parties are “prejudiced” in the etymological sense of that word: They have pre-judged their positions, and are rarely interested in modifying their prior positions. The Two Rivalries Forms of Logic: This logjam is one reason why it is important to discuss the superiority of deductive versus inductive logic — and what could be less fashionable! Going back to Plato and Euclid, the deductive process lends itself to belief modification and consensus agreement as an argument progresses from initial assumptions (First Principles), and ultimately to conclusions. Often, the process linking the basic assumptions to the conclusions is watertight so that, if a participant in the debate agrees with the First Principles, then he or he must agree with the conclusion. Moreover, by their very nature, First Principles are usually compelling and non-controversial. For example, an axiom of number theory states that, for any number n, there is always a next number n+1. Try doing arithmetic without this helper! At the most ambitious level of thinking, the goal is to demonstrate not only that there is a solution to a problem that is consistent with First Principles, but that there can be no other solution. This is referred to as the demonstration of “the existence and uniqueness of a solution.” In American Gridlock, I demonstrate this procedure by showing that there is a unique policy that can drive national health-care expenditure down as a share of GDP while at the same time increasing the quantity of services provided, and the number of people covered. It turns out you can have your cake and eat it too. The same will be true in the case of a policy that could prevent a Lost Decade right now. Both of these examples are discussed just below. One reason for today’s Dialogue of the Deaf is that deductive reasoning of this kind is neither taught to students in school, nor applied in policy analysis. It has gone the way of the Dodo bird. It has been replaced by a form of data-based inductive logic that I call “bastardized induction.” In its broadest form, induction refers to the process of arriving at truths by seeking them in real-world data, data that are transformed and analyzed. Courses in statistics are where students first learn about induction. The root problem of induction was famously identified by the 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume, Adam Smith’s colleague and best friend: No matter how large a sample you have, and no matter how much data you possess, you can never learn the absolute truth as you can via the process of deduction. Seeing ten thousand white swans does not permit an inference that no black swans exist, an inference that all swans are white. Regrettably, what has happened in recent years is that “pure” inductive logic has been replaced by that bastardized form of data analysis all too familiar from today’s Dialogue of the Deaf: As time goes on, each side cherry-picks ever more data to strengthen their prejudiced positions. Thus, positions become ever more shrill. Belief modification and dialectical progress are rarely achieved. In this sense, giving young research associates Excel spreadsheets plus the wealth of information accessible from the internet is proving very dangerous to informed debate. “Factoids” are confused with serious logic, and young people are all but clueless about Hume’s imperative: You cannot data-crunch your way to the Truth. Ever. The Paradox of Information Overload: This last point is directly related to the burden of “information overload” that so many people are now complaining about. Reliance upon inductive logic inevitably leads to the belief that, the more information you have, the better. There is no awareness that “information” is no substitute for serious thought, in particular for the activity of deduction from First Principles. For example, suppose you were attempting to determine a solution to John F. Nash Jr.’s celebrated bargaining problem: How will two different players with different tastes, endowments, and risk appetites agree to divide a pie (money)? Both players would like all the pie, of course, but they will have to compromise at shares of 50/50, 70/30, or whatever. You seek a formula that can predict what the division of the pie will prevail in any situation. Just think of the vast amount of data you might want to crunch to determine which of 40 possible “factors” best explain bargaining behavior, and thus permit the creation of a good forecasting model of pie division. Think of all the experiments you could conduct to discover the dozen or so variables that really matter! In doing so, however, you would never possibly conceive of what the Beautiful Mind discovered via the deduction from five axioms of a theory of bargaining completely devoid of any data: There is only one variable that matters to the bargaining outcome—the degree of risk aversion of Player 1 compared to that of Player 2. Nash showed that, the more risk averse one player is relative to the other, the more he will get “bargained down” to accept a smaller share of the pie. No information overload here. The same holds true in much of physics. Just recall the elegant simplicity of the great “laws” of Newton and Einstein, respectively: F = MA and E = MC2. Only three variables in each. No information overload here either. The irony in all this is the widespread failure to appreciate the complete irrelevance of most of the data now available for problem solving. The great poet T.S. Eliot stressed this point some eighty years ago with his prescient query: “Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? And where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” Bingo! None of this implies that data per se are irrelevant, as they certainly are not. But their primary role is to permit the testing of propositions that have already been generated deductively. Origins of Today’s Dialogue of the Deaf: The chapter offers several explanations for the triumph of sloppy induction over rigorous deduction, and the Dialogue of the Deaf that has resulted: (i) The culture wars of the 1960s and 1970s in which citizens were forced to choose between “absolutist” alternatives posited as black and white extremes in a very politicized environment; (ii) The decline in teaching students the classics — a rich heritage discarded as the detritus of Dead White Males; (iii) The lifestyle changes and foreshortened attention-spans that have made it increasingly profitable for the media to replace compelling step-by-step analyses with partisan sound bites; and (iv) The advent of spreadsheets and of the internet facilitating “cherry-picking induction” (garnering facts that support your view), and fostering today’s fallacious conceit that it is possible to data-crunch your way to the Truth. Professors who know better should assiduously remind students that virtually all great scientific advances were all arrived at by geniuses who deduced their theories from First Principles, often with little if any data. Such theories ranging from game theory, to relativity theory, to quantum theory, to information theory, to the concept of the stored-program computer, to defining and measuring “relative power,” to the Law of Supply and Demand in economics, and even to axiomatic theories of “fair shares” in modern moral theory. Terminating Today’s Dialogue of the Deaf: The chapter concludes with a series of suggestions as to how to tune down today’s the Dialogue of the Deaf and thus end policy gridlock. Here is a sketch of my proposals. First, it must be demonstrated that win-win solutions free of Right-or Left wing biases actually exist. In short, it must be shown that there is an alternative to today’s gridlock. Doing so is the primary purpose of American Gridlock. Second, the media and the schools of government must become involved in an effort to hold public officials accountable for today’s policies that further and further mortgage our children’s future. Along these lines, readers will be heartened and amused by my proposal for a new game of “Gotcha!” that I want to be developed at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. I want government officials publically stigmatized not for their sexual and financial peccadilloes, but rather for their “Idiocy Quotients.” These widely publicized Idiocy Quotients would be posted and updated monthly, with a new 1-to-10 Idiocy Scale scoring the extent of damage their policies will do to tomorrow’s young, and by extension to America’s future. By damage, I mean the dollar value of foregone jobs, income, and social stability. I want TV interviewers and the press in general to hound politicians on such matters — outing them (in the manner of the Amish) for policies that diminish the American future. All this would be part of a strategy to elevate the standards of national debate, and to shift towards forms of reasoning and debate that would lead politicians to adopt win-win policies, once these have been shown to exist. These initiatives would be augmented by a wholly new Civics course to be taught in high schools, a course aimed at getting students to demand better behavior from their politicians. Don’t be cynical. Great progress can be made. Never forget that the invention of double-entry bookkeeping in Genoa over five centuries ago did more to make corrupt businessmen honest than anything else before or after. Investors in an enterprise could finally know where their money was or wasn’t going! Third, I am on the lookout for a Pied Piper to organize the young so that they can gain the voice they currently do not have. This leader will give a voice not only to the Wall Street Occupiers, but to all young people whose future employment and retirement prospects are being shredded by current Washington policies. At present, no Pied Piper exists, but I have identified two young people who might just play this role, and I am backing them. Consider the following moral scandal of our times: Tomorrow’s elderly will regain their lifetime contributions to Social Security over 25 years of retirement (if they live that long) versus less than 5 years for my late father. This is akin to legislating that a woman is one-fifth as good as a man. Or that a gay is one-fifth as good as a straight. Or that a black is one-fifth as good as a white. What is outrageous is that the entitlements policies that lie at the heart of this inequity have been championed by those who call themselves “liberal” and pretend to be concerned with “fairness.” In American Gridlock, I refer to such mental midgets as “phliberals” (phony-liberals) since a true liberal would surely call for give/get retirement packages equalized across generations, not front-loaded in favor of today’s elderly. Yes, a Pied Piper is sorely needed, one who organizes the young and makes them fully aware of their diminished future prospects. Want a great stock market tip? Buy shares in those four companies that have a monopoly in manufacturing pitchforks. Not only will your investment soar in value, but having a few pitchforks around the house may well come in handy once the 99% start coming after you. Chapter 2: Must There Be a Lost Decade of 2011–2020?The remainder of the book centers on concrete public policies. The second chapter addresses what we can do to avoid a Lost Decade marked by subpar economic growth, excessive fiscal budget deficits, and record-high unemployment for a recovery — especially amongst the young. I first review the Seven Headwinds explaining why growth has been and will remain tepid, notwithstanding the stimulus of the “easiest” monetary and fiscal policy in over half a century. I next lay down the four “First Principles” or Basic Assumptions that must be satisfied by any policy proposal aimed at preventing a Lost Decade. Finally, I deduce the existence of a unique policy that satisfies these Basic Assumptions. This takes the form of an extended Marshall Plan dedicated to profitable — not unprofitable — infrastructure of a magnitude not previously proposed. And by infrastructure, I do not mean roads, bridges, and potholes alone! What is perhaps most interesting in this chapter is that, to arrive at a compelling win-win policy proposal, a fundamental rethink is required of what we mean by the term “fiscal deficit,” and indeed of fiscal policy itself. I will demonstrate that “deficit” has become a politically charged word throughout the West, but a term that is devoid of any meaning and is thus a poor guide for public policy. The Seven Headwinds: As is well known, the recent business cycle has been the worst in many decades, as measured both by the aggregate loss of output and by the laggard pace of recovery. Given the extraordinary fiscal and monetary stimulus that were applied to remedy matters, it is unprecedented that, some 30 months into the recovery, GDP has just recently regained its pre-recession output level of 2007. Moreover, the unemployment rate measured most broadly on the U6 scale is still hovering around 15%. Figure 1 puts matters into a long-term perspective. Focus on the structure of recessions and recoveries during the past sixty years.

I identify Seven Headwinds that all but guaranteed the tepid recovery we are experiencing: (1) A depressed labor market, partly due to a very high productivity growth rate exceeding 4% growth during four quarters; (2) Household deleveraging due in part to over-borrowing in the past, and in part to the collapse in the value of their principal asset — their house; (3) Housing industry depression, with the recovery in housing started and in re-hiring laid off construction workers the worst since the 1930s; (4) State and local government contraction of a magnitude never experienced before, with consequences for employment almost as bad as in the construction industry; (5) Lackluster business investment spending within the US, in part due to the absence of an Industrial Revolution like the telecom/internet boom of the 1990s, and partly because of heightened policy uncertainty and its counterpart of corporate risk aversion; (6) High commodity prices and health-care costs, with gas prices, heating oil, and medical costs further weighing on consumer sentiments and budgets; and (7) An inevitable reduction in fiscal stimulus, due in part to growing bond market concerns about 10% deficits, auguring a decade of fiscal drag and austerity. The Four Basic Assumptions or Goals: Whatever policy is adopted to get the economy moving, it must satisfy these four policy requirements — requirements which play the role of First Principles in our analysis. Like any set of First Principles, these national goals should strike you as being as “reasonable” as apple pie and motherhood are desirable. (1) Much more rapid GDP growth; (2) Much reduced Unemployment; (3) A contented bond market unlikely to go on strike; and (4) Infrastructure reconstruction before our infrastructure “goes critical” which is now expected to start happening in many different areas. The Policy Solution: I propose that a Marshall Plan sufficiently large to redress our infrastructure crisis (a good $1 trillion per year) is the only solution that achieves these four goals. By infrastructure, I do not only refer to roads and bridges, but to the nation’s electric and refinery grid, public transportation, and new modes of delivering medical and educational services. These proposals are fleshed out at length in American Gridlock. Your initial skepticism will probably take the form of two questions: First, does the nation have the physical resources for an investment of this magnitude — one which can easily show to be “needed”? Second, does the government have the financial resources to fund such a program? Surely it does not. After all, we are told daily that today’s deficit without any infrastructure spending must itself be slashed. Like many nations in Europe, we confront a decade of fiscal austerity lest the bond market go on strike, and we suffer soaring interest rates and long-term bankruptcy. The only problem is that such conventional wisdom is completely misconceived. We can indeed afford proper infrastructure investment of the right kind, and borrowing the required funds need not upset the bond market. To explain all this, I shall excerpt part of a Socratic Dialogue between myself and President Obama appearing in Chapter II of my book. Economist: The solution lies in redefining the very concept of a “deficit” in a manner that permits a new theory of deficit spending, a theory that applies to the situation in the United States right this minute. When I say “new” here, let me be clear that the basic idea is not so much new as it is currently unrecognized. Out of some 500 op-ed columns on the subject of deficit spending that I have read in the past few years, I have seen perhaps four articles that set forth the basic thrust of this approach. Yet none of these four suggested that the proposed approach to deficit spending could simultaneously solve all four crises that the United States now confronts if it is to avoid a Lost Decade. Nor have I ever seen this approach justified by first principles stemming from the Arrow-Kurz theory of optimal fiscal policy lying at the foundation macroeconomic theory. [This very advanced theory offers a second justification from First Principles of my policy proposals, and is discussed at length in the book.] Mr. President, given the urgency of the U.S. crisis, and given today’s strong prejudices against ongoing large fiscal deficits, a very strong justification is needed for what I am going to propose. The Arrow-Kurz theory provides this. President: Can you explain the main point here in the simplest possible terms? And please be sure to make clear how can the nation afford your highly ambitious plan. There will be many skeptics. Economist: Yes. Please consider Figure 2, which contrasts the fiscal status of two countries with ostensibly identical deficits. Assume that Country A’s government spends $4 trillion on defense, administrative costs, interest expenses on its debt, and transfer payments such as Social Security and Medicare. Its tax revenues of $3 trillion fall $1 trillion short of this $4 trillion, so that the nation runs a deficit of $1 trillion. More specifically, its Treasury Department will have to issue $1 trillion in new government bonds. The expense of servicing this new debt (or repaying it) will fall on tomorrow’s taxpayers, who just might renege on it if total debt gets too large. It is this prospect that increasingly worries the bond market.

As the magnitude of total national debt outstanding grows each year because of these marginal additions to total debt (i.e., each year’s deficit), a point will be reached where the bond market fears future insolvency, or else a printing away of the debt. As a result, investors will demand higher yields, which crimp the growth rate of the economy, and cause the cost of refinancing the debt to explode. The infamous “debt trap” could soon be reached—a fiscal red hole from which few nations escape. Country A is modeled after the United States, of course, and during 2010–2011 investors worldwide began to question its long-term solvency, especially in light of the inability of both political parties to cope with runaway spending. President: But what is different about Country B, whose revenues and outlays are identical to those of country A, but which you claim in our figure has no deficit? Is this a trick? Are you the Houdini of macroeconomics? Economist: Thank you, but no. Country B differs in one regard: of its total $4 trillion in government spending, $1 trillion of this is spent on profitable investments (human capital and infrastructure investments) which are certified by an independent research organization to generate a positive expected return on capital, as calculated by the methods of the modern theory of public finance. The remaining $3 trillion are normal expenditures on defense, interest payments, administrative costs, and transfer payments like Social Security and Medicare. When bond market vigilantes understand this breakout, they see a nation whose unproductive but necessary government spending of $3 trillion is fully matched by current tax revenue ass the figure makes clear. As a result, in Country B there is no deficit from unproductive spending in Country B that does not pay for itself. On the other hand, the nation is borrowing an extra trillion dollars to invest in projects that are “certifiably productive,” as it were, and that pay for themselves over time in the same way that productive capital investments in the private sector pay off. So, overall, no new debt has been chalked up that future generations must service. That is why the figure shows a deficit of zero for Country B. The bond markets are placated, interest rates are not driven up, and large-scale government spending of a disciplined kind continues, thus preventing fiscal drag. President: I am supposed to think of Country A as America today, and Country B as America the way it could be tomorrow, correct? Economist: Yes. More specifically, think of Country B as the America that would be, were Congress able to redirect a good chunk of government spending (up to $1 trillion per year) away from existing spending toward productive spending. Historically, such spending included investments in the highway system, the space program, the Internet (known originally as the DARPANET), the interstate highway system, R&D, the Erie canal system, the railroads, the energy grid, water resources (the Hoover Dam), and so forth. Congress is not to cut $1 trillion of government spending as many deficit hawks would like, but which would drag down economic growth and employment. Rather, it is to reconfigure total spending in the manner required to maximize GDP growth, employment growth, and productivity. As a result, there are no net layoffs, and no fiscal drag at all. President: So your sleight of hand is to introduce two kinds of deficits, “good” and “bad” deficits that differ according to the type of spending that generated the deficit. Economist: Yes. Emphasis accordingly must shift away from the overall size of the deficit to its composition of good versus bad spending. I am not claiming here that nonproductive spending is bad per se, as it is not. But in the future, such spending must be matched by tax revenues so as to no longer increase “bad debt,” the burden on future Americans that rightly troubles bond market vigilantes. This is not true in the case of “good debt” incurred for profitable infrastructure spending that earns a positive rate of return on invested capital. In American Gridlock, much of the subsequent Socratic Dialogue addresses the President’s concerns about ancillary issues such as: What exactly is productive versus unproductive infrastructure investment? How is “rate of return” measured in the case of public as opposed to private investment projects? What kind of decision-making process must be used to identify worthwhile projects, and what can be done to guarantee that decisions are not politicized (hint, a new form of international investment bank with foreign investors welcome)? How can we redress the obstacle of NIMBYISM, both by executive orders of the kind President Obama cited in his recent State of the Union address, and by edicts the Supreme Court? (Invoking national security concerns can go a long way here, as was the case in building the Interstate Highway System.) Finally, a much deeper justification of the proposed Marshall Plan is given by utilizing the advanced theory of “optimal fiscal deficits” set forth by Kenneth Arrow and Mordecai Kurz in their treatise on this subject, “Public Investment, Rate of Return, and Optimal Fiscal Policy.” There are two important by-products of the proposed plan. First, the productive nature of the spending will by definition increase the productivity of capital and labor — both good for GDP growth. Second, each dollar spent on profitable investment creates nearly three times as many jobs via “multiplier/accelerator effects” as the same dollar spent on transfer payments (e.g., keeping state employees in their existing jobs). All in all, it is demonstrated in the book that the proposed Marshall Plan is the only policy capable of satisfying the four policy goals that play the role of First Principles in resolving the Lost Decade crisis. Chapter 3: Resolving the Entitlements Spending CrisisThe third chapter reviews the coming crisis in paying for tomorrow’s elderly, including ballooning costs of Social Security and Medicare. Estimates of the nation’s unfunded liabilities for such programs range between $40 – $60 trillion over the next half century. Contrary to what is usually supposed Social Security does not pose that great a problem. As is shown at the end of Chapter 3, there are several ways to render Social Security solvent for the next seventy-five years. A combination of reducing the rate of “indexing” of payments, and increasing the retirement age to 70 will suffice, providing that reforms are introduced very soon. Far the greater problem lies with exploding health-care costs, currently 18.3% of GDP and likely to rise to well over 30%. This represents near bankruptcy for the nation. President Obama’s Reform Act of 2008 represented a path-breaking attempt to bring this beast under control. In particular, he sought to restrain the growth rate of health-care spending, while at the same time increasing “access” to coverage by millions of Americans who are currently uninsured. Subsequently, it has been recognized that, if anything, ObamaCare will raise total expenditure on health care faster than would have occurred without his provisions for cost controls and increased access. In my own view, the verdict is still out on this matter. Might it be possible that we can have our cake and eat it too in health-care reform, just as we could in redeeming today’s Lost Decade? Is there a win-win solution, that is, one that does not require a Left-wing universal coverage system that would bankrupt the nation, or a Right-wing free market solution that would end up providing little if any coverage for the bottom half of Americans? Yes, there is a win-win solution to this problem, one that will please people on both sides of the political aisle. This solution is set forth in detail in the book, and is proved to be the only solution satisfying three Basic Assumptions (First Principles) that most anyone will find compelling. The Three Basic Assumptions for an Optimal Health-care System: I propose the following three goals for an optimal health-care system: Goal 1 – Greatly increased access to health care. This will be made possible by greater insurance coverage per person, and by an increased in the number of people covered. This first goal was central to President Obama’s plan. Goal 2 – Greatly increased supply of health-care services provided. This goal is often overlooked, and was bypassed by most provisions of ObamaCare. Yet it must be satisfied as a counterpart of today’s emphasis on increases access. To understand why, suppose that all workers receive health insurance supplied by their employers. Suppose in addition that, when a worker calls his doctor for an appointment that he can now afford due to his new insurance, the doctor’s phone never answers. Under ObamaCare, this will almost certainly happen for two reasons. First, some 25% of practicing physicians are due to retire in 20 years. Second, new “cost control” provisions lowering doctors’ reimbursement rates will drive many doctors out of business. In this event, the lure of “more access” is a red herring. The purpose of my second goal is to require that a far greater quantity services are supplied to match the increase in demand driven by greatly expanded insurance coverage. Goal 3 – An ultimate shrinkage of total health-care expenditures as a share of GDP: On the surface, the possibility of a greatly expanded health-care sector (greater levels of demand and supply) would seem completely incompatible with reducing the nation’s total expenditure on health-care services. Please note that I want to reduce total expenditure in absolute terms, not simply slow the growth rate of expenditure as President Obama sought to achieve. Can we have our cake and eat it to in resolving the health-care crisis? Yes we can. Before demonstrating this result, please recall the true meaning of the law of supply and demand in Econ 101. We are often tempted to predict future market conditions (price and quantities) by stating that supply will increase faster than demand, or vice versa. But to do so is illegitimate and has no meaning. This is because supply (a number like 20 bushels of wheat) will always equal demand, so one cannot increase faster or slower than the other. Thus, the principal lesson of basic microeconomics is that, when we state that supply will increase faster than demand, we mean that the supply curve (a function — not a number) will shift out to the right faster than the demand curve. Or vice versa. Keeping this point in mind, we have: Principal Result: Goals 1, 2, and 3 can all be satisfied provided the following condition holds true. If it does not hold true, then total expenditure as a share of GDP will rise without bound, eventually bankrupting the nation assuming that the public continues to demand health care. The required condition is that the aggregate health-care supply curve must shift out to the right more rapidly than the aggregate demand curve does. This is true no matter how fast the demand curve might shift out, and no matter how small the difference is between the rate of shift of the supply curve versus the demand curve. A geometric sketch of the proof of this proposition is provided just below in the context of Figure 3. In studying this, recall that total expenditure — the variable of principal interest to the nation — is always given as the arithmetic product of the price/quantity equilibrium coordinates in any market. If equilibrium (supply = demand) quantity is 12 units, and equilibrium (supply = demand) price is $7, then the total expenditure is 12 x $7 = $94. Total expenditure of any market equilibrium can thus be viewed as the geometric area of the rectangle defined by the coordinates of the equilibrium. Two such areas corresponding to the two equilibria E and E* are depicted as the two shaded areas in the figure.

Sketch of Proof: Think of the two market equilibria shown E and E* as representing the health-care market “before” and “after” new policies are put in place that satisfy our fundamental Supply/Demand condition. The numbers shown for each axis are hypothetical and illustrative. The period shown could represent, say, 15 years. Note in Figure 3 that the supply curve shifts outward far more than the demand curve does over the period in question, as required by our condition. Since the outward supply shift must be greater than the outward demand shift each and every year, by assumption, the cumulative gap between the location of the supply and demand curve grows larger and larger over time. It is this cumulative gap that is shown in the graph over the hypothetical period of 15 years. Now note that the total expenditure on health care (to be interpreted as a share of GDP) decreases by 25 percent. This is proved by the fact that the area defined by the price/quantity rectangle associated with the new equilibrium is 25% smaller than the area of the initial rectangle. More specifically, the area $4 x 4 = $16 defined by the first market equilibrium drops to $2 x 6 = $12 in the new equilibrium, a 25 percent reduction in total expenditure. Note that this is true even though demand has increased, and even though the quantity of services delivered has increased significantly, as desired, rising 50 percent from 4 to 6 units as seen on the horizontal axis. On the other hand, the price per unit of aggregate service has decreased 50% from $4 to $2 on the vertical axis. In short, a much-increased quantity of services gets delivered, unit costs to patients and their insurers are lowered, and the total expenditure to the nation decreases. The “proof” here is purely geometric, and only applies to the example appearing in our graphs. But the underlying logic is fully general, as is shown in Appendix B tucked in the back of American Gridlock. Conclusion: This is the main result showing how we can have our cake and eat it too. But since this result refers to supply and demand in aggregate in the health-care sector, it is necessary to link this over-arching requirement with policy reforms at the micro level. Accordingly, the last part of Chapter 3 explores this macro-micro linkage, e.g., its implications for tort reform, for expert-system automation, and for many other dimensions of health-care reform. The main point is that, whatever the policy being considered in any given micro-market, that policy must ideally cause the supply curve in that market to shift out faster than the demand curve. This provides a wholly novel way in which to assess the myriad micro-reform proposals that appear daily in the nation’s newspapers. Postscript – Lack of Ideological Bias: In this first of a two-part synopsis of American Gridlock, I hope it will have been clear that no use has been made of Left or Right-wing prejudices. How can anyone be against remedies for bringing today’s Dialogue of the Deaf to an end? Who can be against a policy for preventing a Lost Decade that solves all four of the nation’s greatest challenges in one fell swoop? Who can be against more health care for more people along with a reduction in total health-care expenditure? For one last time, recall that demonstrating the existence of win-win policies of these kinds is the principal goal of this book. H. Woody Brock, Ph.D. |

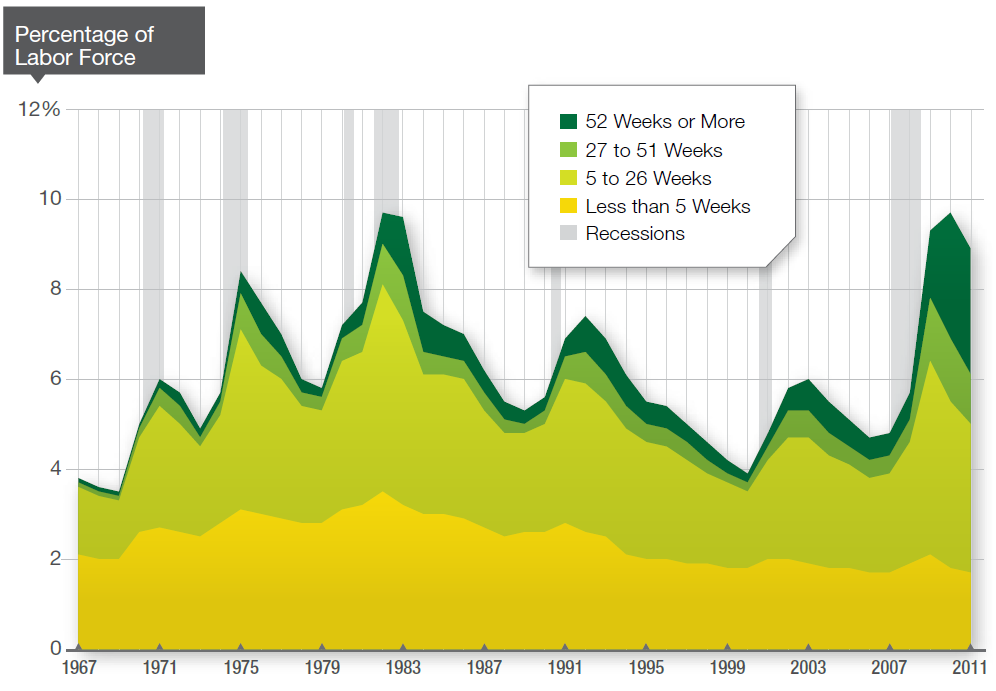

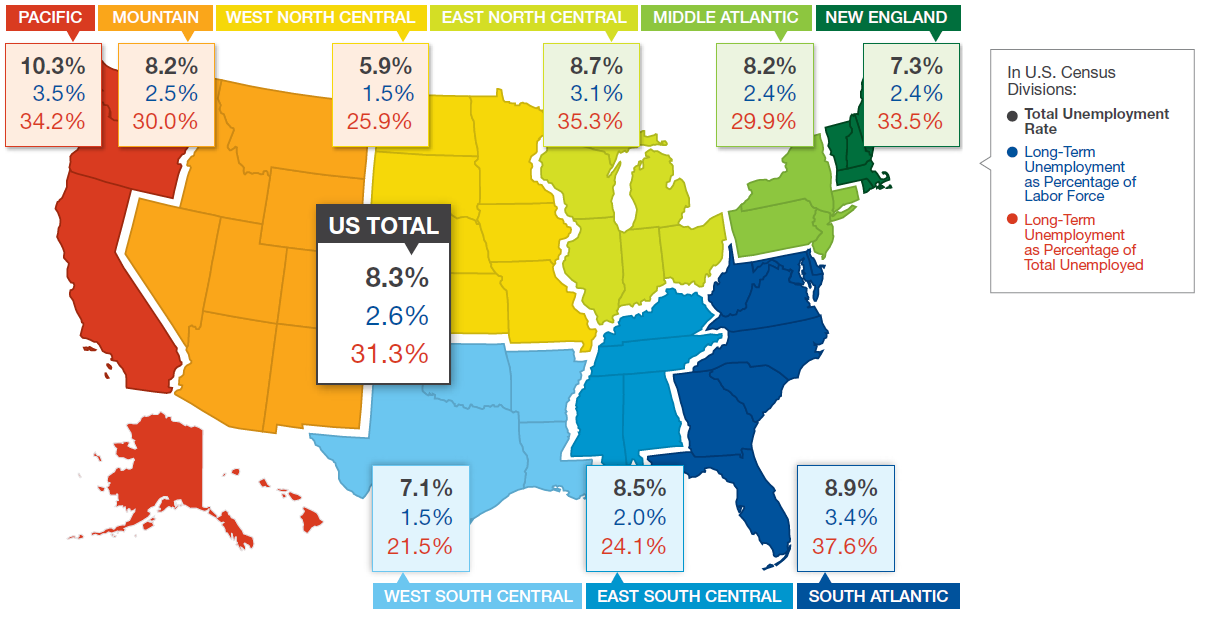

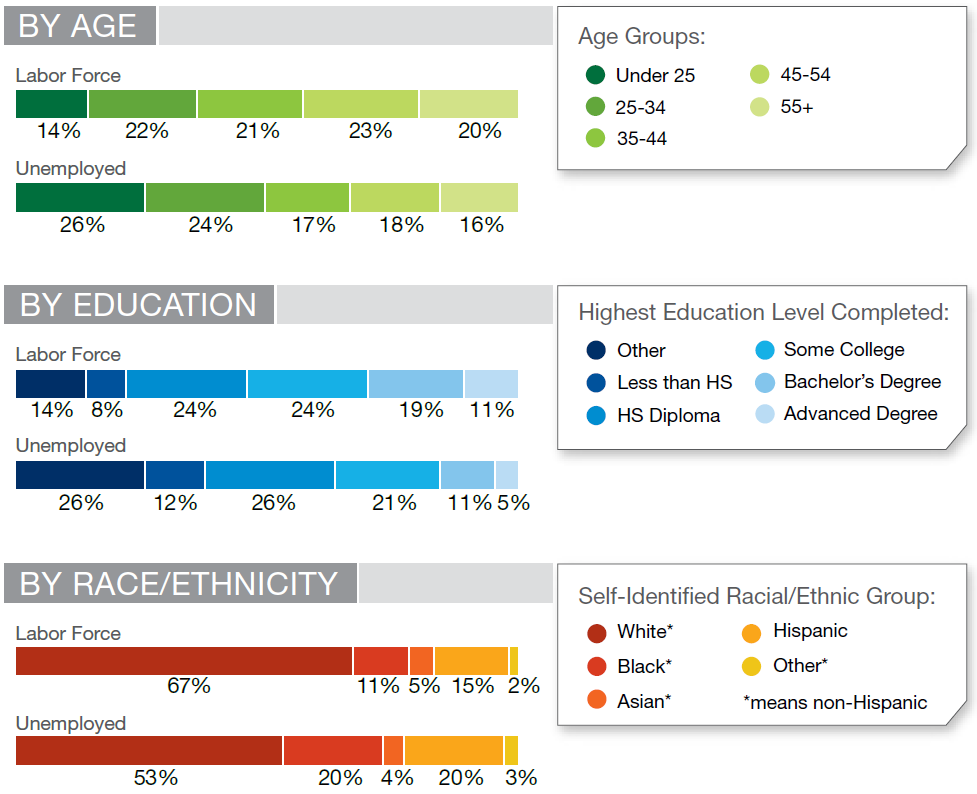

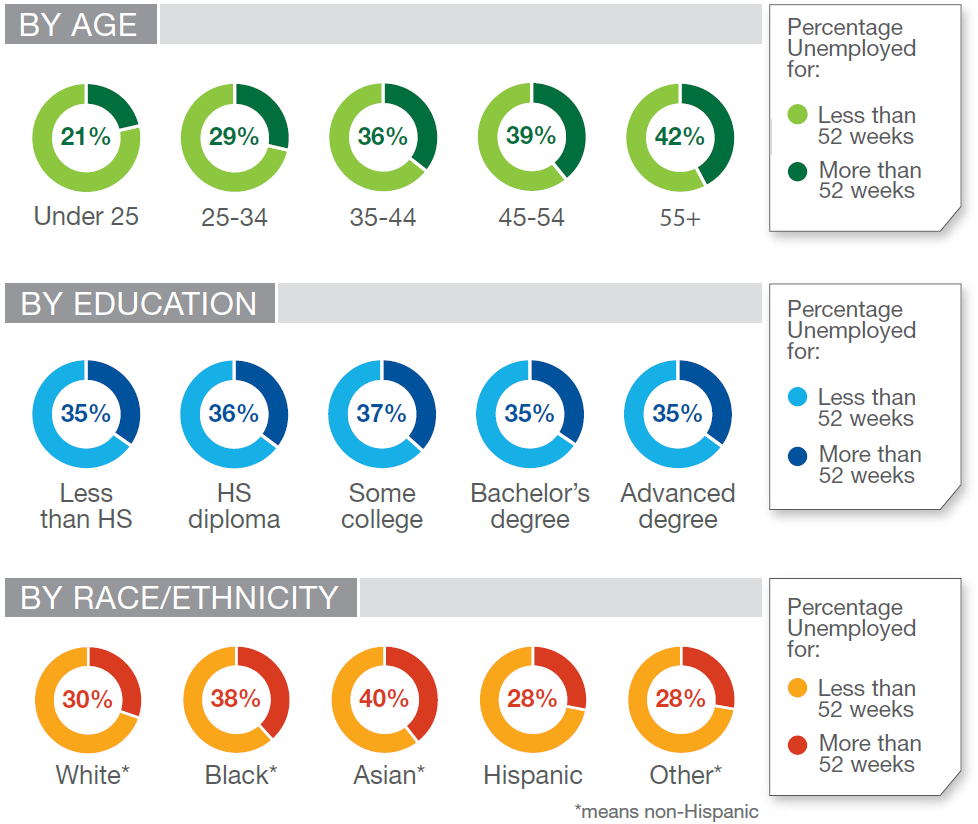

| Five Long-Term Unemployment Questions Posted: 02 Feb 2012 11:30 AM PST Tomorrow is (yet again) NFP day. While everyone is worrying about whether the December numbers were merely seasonal, we should also consider some of the longer term trends in Unemployment. These have major repercussions for Retail Sales and the ongoing Housing Weakness. Fortunately, Pew Trusts gave us a full overview: > ~~~ Where are the Long-Term Unemployed? ~~~ More charts after the jump

Labor Force and Unemployed Populations by Age, Education and Race/Ethnicity, Quarter 4, 2011 ~~~ Long-Term Unemployment as a Percentage of the Total Unemployed ~~~ Are Workers Being Laid Off Permanently? Permanent and Temporary Layoffs as a Percentage of the Total Unemployed Source: Pew Trusts |

| Posted: 02 Feb 2012 09:30 AM PST |

| Posted: 02 Feb 2012 09:00 AM PST My double dose of Bloomberg (Radio/TV) slowed down my reads – here they are for your lunchtime reading pleasure:

What are you reading? > |

| Posted: 02 Feb 2012 08:00 AM PST |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment