The Big Picture |

- 10 Monday PM Reads

- Gross: Don’t Believe the Economic Stimulus Hype

- Hands-On With the Most Frightening Lamborghini Ever

- Pogue, Gruber Discuss iPhone 5 on Charlie Rose

- With commodity prices, inflation expectations in further

- Global Equity Markets: Returns and Composition

- Dallas Fed Fisher on Monetary Policy (with Reference to Tommy Tune, Nicole Parent, the FOMC, Velcro, Drunken Sailors and Congress)

- 10 Monday AM Reads

- Dark Pools: High-Speed Traders, A.I. Bandits, and the Threat to the Global Financial System

- QE Infinity and US Stock Market

| Posted: 24 Sep 2012 02:29 PM PDT My afternoon train reading:

What are you reading?

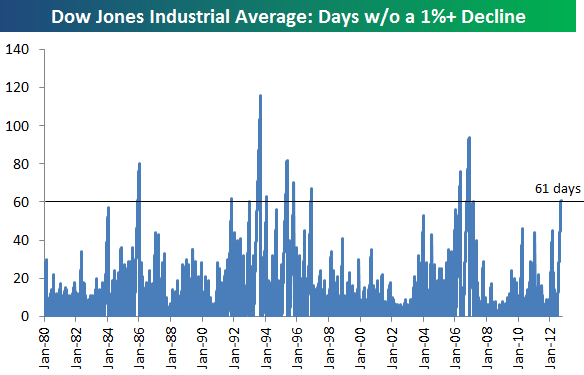

61 Days Without a 1%+ Decline | |

| Gross: Don’t Believe the Economic Stimulus Hype Posted: 24 Sep 2012 02:06 PM PDT Some are claiming the iPhone 5 can singlehandedly stimulate the economy, but the cash being spent on the device would pack a bigger punch deployed elsewhere, says Daniel Gross. The Annoying iPhone 5 Frenzy

he Annoying iPhone 5 Frenzy: Don't Believe the Economic Stimulus Hype (Daily Beast) | |

| Hands-On With the Most Frightening Lamborghini Ever Posted: 24 Sep 2012 01:47 PM PDT Stephan Winkelmann, CEO of Lamborghini SPA, gives Bloomberg an up close tour of the Lamborghini Sesto Elemento, a 217 Mph supercar constructed largely with carbon fiber that claims a 0-60 acceleration of 2.5 seconds. A limited run of 20 units will reportedly be manufactured over the next year.

| |

| Pogue, Gruber Discuss iPhone 5 on Charlie Rose Posted: 24 Sep 2012 12:00 PM PDT New York Times technology columnist David Pogue and Daring Fireball tech blogger John Gruber discuss the iPhone 5.

| |

| With commodity prices, inflation expectations in further Posted: 24 Sep 2012 11:13 AM PDT The rise in the implied inflation rate in 10 yr TIPS today is back down to the close of the day the Fed announced QE Tres on Thursday the 13th at 2.47% after rising to as high as 2.64% on a closing basis after. Inflation expectations 5 yrs out is at 2.19%, above the 2.14% closing level on Wed the 12th but below the close the following day of 2.26%. The 5y5y forward breakeven is in as well but less so at 2.9% vs 2.78% the day before the Fed’s move. It was as high as 3.05% intraday in the days post Fed news. The obvious factor in the change of heart over the past week is the drop in the CRB index which is today at a one month low as economic factors temporarily outweigh monetary ones. When the dust settles though, the only thing the Fed will leave us I believe is stagflation. | |

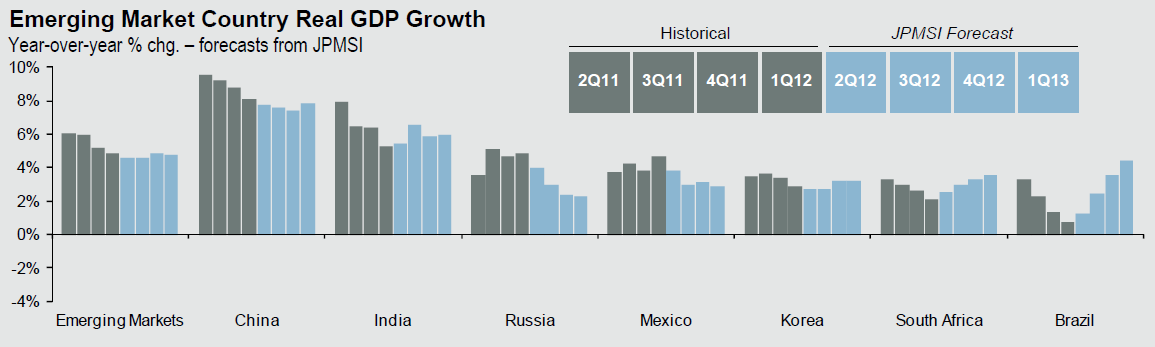

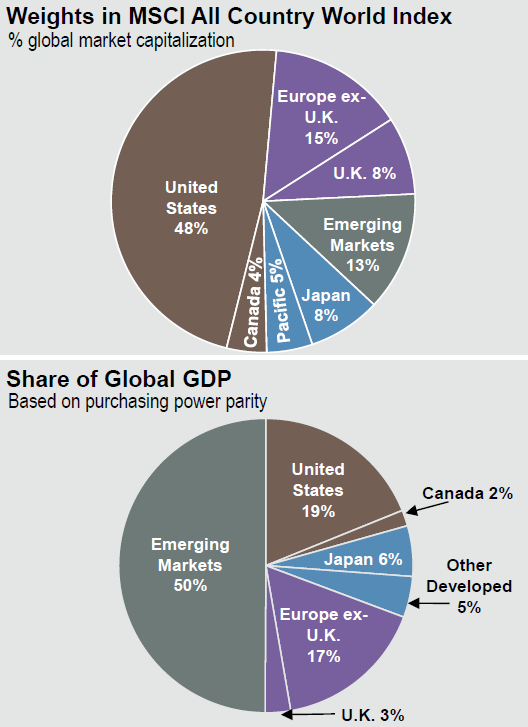

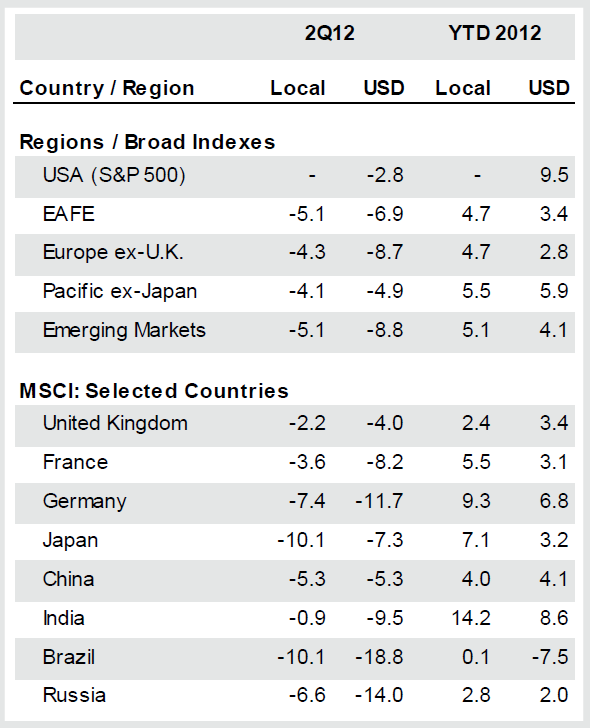

| Global Equity Markets: Returns and Composition Posted: 24 Sep 2012 09:15 AM PDT | |

| Posted: 24 Sep 2012 08:00 AM PDT Comments to the Harvard Club of New York City on Monetary Policy (With Reference to Tommy Tune, Nicole Parent, the FOMC, Velcro, Drunken Sailors and Congress)Remarks before the Harvard Club of New York City

Thank you, Nicole [Parent]. And thanks to the Harvard Club of New York for including me in your speaker series. It is quite something to see one's picture on the cover of the Harvard Club of New York Bulletin wedged between that of Tommy Tune and Nina Khrushcheva, Nikita Khrushchev's great-granddaughter. My wife Nancy and I celebrated our 39th anniversary on Sept. 8. Knowing that she has seen and loved everything our fellow Texan Tommy Tune has ever done on the musical stage, and having grown up with the image of Nikita Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union banging his shoe on the podium of the United Nations and saying, "We will bury you!" I thought I would impress her that evening by showing her the Bulletin. "In your wildest dreams," I asked her, "did you ever think that the skinny, long-haired boy you married 39 years ago would be headlining a speaker series alongside Tommy Tune and Nikita Khrushchev's great-granddaughter?" Her answer was classic: "Richard, we have been married for four decades. I hate to disappoint you sweetheart, but you don't appear in my wildest dreams." A Word About Nicole ParentI am here to speak to you about monetary policy. But before I start, I am going to take advantage of your undivided attention to announce to all assembled here tonight that the former president of this club and my fellow Harvard Overseer, Nicole Parent, is engaged to be married. Nicole, may your marriage last at least 39 years and may you be blessed with the wildest of dreams and the best of life. A Different PerspectiveIn addition to the Algonquin, there are two iconic buildings on this side of West 44th Street. One is the New York Yacht Club; the other is the Harvard Club. I mention this because the close proximity of these two buildings suggests something of a biographical metaphor. I spent four years at a Naval Academy prep school before becoming a midshipman in 1967 at Annapolis, where I majored in engineering and learned the craft of seamanship and naval warfare. Then, in 1969, Harvard kindly recruited me in as a transfer student. Two years later, I graduated with a degree in economics. In thinking through many of the policy issues that confront me as a member of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), I tend to combine both backgrounds, as well as an orientation framed by having an MBA and spending a significant portion of my career as a banker and market operator. My perspective is thus framed from the viewpoint of an engineer, an MBA and a former market operator—not as a PhD economist. For most economic theoreticians, hundreds of billions, or even trillions, of dollars are inputs into a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model and other econometric equations. To a banker, businessperson or market operator, these are real dollars that have to be thought of within the framework of a transmission mechanism that needs to get the money from its origin at the Fed into the real economy with maximum efficacy. My focus tends toward the practicable—how to harness theory to devise a workable solution to the problems that confront a central banker. There are many superb PhD theorists among the 19 members of the FOMC and support staff. There are only a handful of us—four, to be exact—who have worked as bankers or in the financial markets. Tonight, I am going to provide my take on the FOMC's most recent decision to embark on a new round of quantitative easing focused on mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Given my background, and the fact that the Navy is once again welcome back in Harvard Yard, I'll ask your forbearance if I use some seafaring references.[1] As the book kindly cited by Nicole says, I am given to providing the "straight skinny."[2] I am a Texan. I speak bluntly and directly. I am not given to circumlocution, and I checked diplomacy at the door when I gave up my post as an ambassador and trade negotiator. Please don't take offense and please bear in mind that my comments this evening are mine alone; I do not claim to speak for anybody else in the Federal Reserve System. I shall start my remarks with what I argued at last week's FOMC meeting, then finish with some comments on the outcome of that meeting and what needs to be done next. The Recent FOMC MeetingIt will come as no surprise to those who know me that I did not argue in favor of additional monetary accommodation during our meetings last week. I have repeatedly made it clear, in internal FOMC deliberations and in public speeches, that I believe that with each program we undertake to venture further in that direction, we are sailing deeper into uncharted waters. We are blessed at the Fed with sophisticated econometric models and superb analysts. We can easily conjure up plausible theories as to what we will do when it comes to our next tack or eventually reversing course. The truth, however, is that nobody on the committee, nor on our staffs at the Board of Governors and the 12 Banks, really knows what is holding back the economy. Nobody really knows what will work to get the economy back on course. And nobody—in fact, no central bank anywhere on the planet—has the experience of successfully navigating a return home from the place in which we now find ourselves. No central bank—not, at least, the Federal Reserve—has ever been on this cruise before. This much we do know: Our engine room is already flush with $1.6 trillion in excess private bank reserves owned by the banking sector and held by the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. Trillions more are sitting on the sidelines in corporate coffers. On top of all that, a significant amount of underemployed cash—or fuel for investment—is burning a hole in the pockets of money market funds and other nondepository financial operators. This begs the question: Why would the Fed provision to shovel billions in additional liquidity into the economy's boiler when so much is presently lying fallow? Great battles at sea are fought with modern analytical tools and the most sophisticated IT and advanced weaponry available. Fleet commanders, like central bankers, use every bit of the intelligence, technology and theory at their command. But ultimately, just as with great engagements at sea, the decisive factor is judgment. In forming their judgments, fleet commanders rely upon briefings from their senior officer corps on the elements, on the conditions at hand and on their tactical and strategic recommendations before deciding on the proper course of action. As you all know, the Federal Reserve's mission is mandated by the Congress. It calls for us to steer a monetary course according to a dual mandate—we are charged with maintaining price stability while conducting policy so as to best assist in achieving full employment. Most all of the FOMC members—the senior officer corps of the Federal Reserve fleet—have surveyed the horizon from their different watch stations and agree that inflation is not an immediately foreseeable threat. Over the past week, however, there has been a noticeable increase in the longer-term inflation expectations inferred from bond yields. These inferences can be volatile and are not always reliable, but a sustained increase would suggest incipient doubts about our commitment to the Bernanke Doctrine of sailing on a course consistent with 2 percent long-term inflation. I believe that even the slightest deviation from this course could induce some debilitating mal de mer in the markets. Charting a Course to Full Employment with Businesses at 'Sixes and Sevens'In the current tumultuous economic sea, facing strong headwinds common in the aftermath of financial crises and balance-sheet recessions, our desired port is increased employment. Certain theories and various hypothetical studies and models tell us that flooding the markets with copious amounts of cheap, plentiful liquidity will lift final demand, both through the "wealth effect" channel and by directly stimulating businesses to expand and hire. And yet from the perspective of my watch station—as I have reported time and again—the very people we wish to stoke consumption and final demand by creating jobs and expanding business fixed investment are not responding to our policy initiatives as well as theory might suggest. Surveys of small and medium-size businesses, the wellsprings of job creation, are telling us that nine out of 10 of those businesses are either not interested in borrowing or have no problem accessing cheap financing if they want it. The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), for example, makes clear that monetary policy is not on its members' radar screen of concerns, except that it raises fear among some of future inflationary consequences; the principal concern of the randomly sampled small businesses surveyed by the NFIB is with regulatory and fiscal uncertainty.[3] This is not terribly difficult to understand: If you are a small business, especially, and not only if you operate as an S corporation or as a limited liability company, you are stymied by not knowing what your tax rate will be in future years, or how you should cost out the social overhead of your employees or how you should budget for the proliferation of regulations flowing from Washington. With regard to business fixed investment and job-creating capital expenditures (capex), the math is pretty straightforward: Big businesses dominate that theater. Most all of these businesses have abundant cash reserves or access to money, many at negative real interest rates. I have repeatedly reported to the committee that the CEOs I personally survey will simply not be motivated by further interest rate cuts to invest domestically—beyond their maintenance needs—in job-creating capex. In preparing for this last FOMC meeting, I specifically asked my corporate interlocutors the following question: "If your costs of borrowing were to decrease by 25 or more basis points, would this induce you to spend more on job-creating expansion?" The answer from nine out of 10 was "No." The responses of those I surveyed are best summarized by the comments of one of the most highly respected CEOs in the country: "We are in 'stall mode,' stuck like Velcro, until the fog of uncertainty surrounding fiscal policy and the debacle in Europe lifts. In the meantime, anything further monetary accommodation induces in the form of cheaper capital will go to buying back our stock." This is not an insignificant sounding, coming as it did from the CEO of a company that has the capacity to spend upward of $15 billion on capex. To be sure, buying in stock will have a positive wealth effect on that company's shareholders, but putting the equivalent amount of money to work in spending on plant and equipment would put more people back to work more quickly. Another CEO of a large corporation provided me with an additional source of uncertainty. In this CEO's words, China "may be transitioning toward becoming the caboose of the global economy rather than its engine." This may be a tad bit hyperbolic, but it indicates there is growing uncertainty about the great emerging economy that was once considered an eternal fountain of future demand. With the disaster that our nation's fiscal policy has become and with uncertainty prevailing over the economic condition of both Europe and China and the prospects for final demand growth here at home, it is no small wonder that businesses are at sixes and sevens in committing to expansion of the kind we need to propel job creation. The Duke University SurveyMy assessment of the efficacy of further monetary accommodation in encouraging job-creating investment among operating businesses was recently confirmed by a more rigorous analysis in the Global Business Outlook Survey of chief financial officers by the Fuqua School of Business at Duke University—the Harvard of the South—in September.[4] Of the 887 CFOs surveyed, only 129, or 14.5 percent, listed "credit markets/interest rates" among the top three concerns facing their corporations. In contrast, 43 percent listed consumer demand and 41 percent cited federal government policies. Ranking third on their list was price pressures from competitors (thus affirming most hawks' sense that inflationary pressure is presently sedentary); fourth was global financial instability. The analysts at Duke summarized their findings as follows: "CFOs believe that a monetary action would not be particularly effective. Ninety-one percent of firms say that they would not change their investment plans even if interest rates dropped by 1 percent, and 84 percent say that they would not change investment plans if interest rates dropped by 2 percent." Citing the Evidence of the Unsophisticated and the Sophisticates AlikeCiting these observations, I suggested last week that the committee might consider the efficacy of further monetary accommodation. When I raised this point inside the Fed and in public speeches, some suggested that perhaps my corporate contacts were "not sophisticated" in the workings of monetary policy and could not see the whole picture from their vantage point. True. But final demand does not spring from thin air. "Sophisticated" or not, these business operators are the target of our policy initiatives: You cannot have consumption and growth in final demand without income growth; you cannot grow income without job creation; you cannot create jobs unless those who have the capacity to hire people—private sector employers—go out and hire. In the period between the August FOMC meeting and the meeting last week, some very prominent academic and policy sophisticates also questioned the efficacy of large-scale asset purchases. Among them were Michael Woodford of Columbia University—a former colleague of Ben Bernanke's when they were at Princeton—and Bill White of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and formerly of the Bank for International Settlements, and others. Like me, Professor Woodford argues that the economy would not benefit from additional liquidity. Like me, he argues that large-scale asset purchases and maturity-extension programs like Operation Twist are unlikely to appreciably stimulate private borrowing activity through portfolio-balance or term-premium effects.[5] And as for Bill White—a globally respected economist who stood up to convention and predicted in 2003 that policies being pursued at the time would engender the financial crisis of 2008–09—here is what he wrote in a particularly thought-provoking paper a week before the Fed's annual symposium last month at Jackson Hole, Wyo.:[6] "In this paper, an attempt is made to evaluate the desirability of ultra easy monetary policy by weighing up the balance of the desirable short run effects and the undesirable longer run effects—the unintended consequences … It is suggested that there are grounds to believe that monetary stimulus operating through traditional ('flow') channels might now be less effective in stimulating aggregate demand than is commonly asserted … It is further contended that cumulative ('stock') effects provide negative feedback mechanisms that also weaken growth over time … In the face of such 'stock' effects, stimulative policies that have worked in the past eventually lose their effectiveness. "It is also argued … that, over time, easy monetary policies threaten the health of financial institutions and the functioning of financial markets, which are increasingly intertwined. This provides another negative feedback loop to threaten growth. Further, such policies threaten the 'independence' of central banks, and can encourage imprudent behavior on the part of governments. In effect, easy monetary policies can lead to moral hazard on a grand scale. Further, once on such a path, 'exit' becomes extremely difficult. Finally, easy monetary policy also has distributional effects, favoring debtors over creditors and the senior management of banks in particular. None of these 'unintended consequences' could be remotely described as desirable." I do not necessarily agree with all of either Woodford's or White's arguments, but in light of my soundings of unsophisticates and sophisticates alike, I felt an urge at the meeting last week to tie the chairman to the mast, Odyssean-style, and to stuff wax in the ears of my fellow committee members, in order to resist the Siren call of further large-scale asset purchases. But I have no such powers. I am only one officer in the loyal crew that sails under the command of Admiral Bernanke. My reports were given a fair hearing. But neither they, nor the arguments of others who questioned the need to provide further accommodation, carried the day, and a decision was made. Having weighed the various tactical and strategic arguments of his officer corps, our helmsman decided to call down to the engine room and request that more coal be shoveled into the economy's boilers. It was decided that further accommodation would be required in the form of mortgage-backed securities purchases of $40 billion per month and that Operation Twist and the reinvestment of principal payments from our current holdings of agency debt and MBS would be maintained: A total of $85 billion a month in additional accommodation would be added to the system at least through the end of the year. For added measure, the committee announced that if the outlook for employment does not improve "substantially," it "will continue its purchases of agency mortgage-backed securities, undertake additional asset purchases, and employ its other policy tools as appropriate until such improvement is achieved." As it always does, the FOMC noted that it will "take appropriate account of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases."[7] A Fair Assessment and a PrayerEven though I am skeptical about the efficacy of large-scale asset purchases, I understand the logic of concentrating on MBS. The program could help offset some of the drag from higher government-sponsored entities' fees that have been recently levied, will likely lower the spreads between MBS and Treasuries and should put further juice behind the housing market—one of three durable-goods sectors that is assisting the recovery and yet is operating well below long-run potential (the other two sectors are aircraft and automobiles). The general effects of inducing more refinancing may aid housing and households in other ways. Lower mortgage rates could help improve the discretionary spending power of some homeowners. Underwater homeowners might have added incentive to continue meeting mortgage payments, spurring demand and preventing underwater mortgages from sinking the emerging housing recovery. Of course, much depends on the transmission mechanism for mortgages, as my colleague Bill Dudley spoke about yesterday. Despite my doubts about its efficacy, I pray this latest initiative will work. Since the announcement, interest rates on 30-year mortgage commitments have fallen about one-quarter percentage point—about what I had expected—so, so far, so good. Our Dysfunctional Congress and Drunken SailorsI would point out to those who reacted with some invective to the committee's decision, especially those from political corners, that it was the Congress that gave the Fed its dual mandate. That very same Congress is doing nothing to motivate business to expand and put people back to work. Our operating charter calls for us to conduct policy aimed at achieving full employment in addition to preserving price stability. A future Congress might restrict us to a single mandate—like other central banks in the world operate under—focused solely on price stability. But unless or until that is done, we have to deliver on what the American people, as conveyed by their elected representatives, expect of us. One of the most important lessons learned during the economic recovery is that there is a limit to what monetary policy alone can achieve. The responsibility for stimulating economic growth must be shared with fiscal policy. Ironically, and sadly, Congress is doing nothing to incent job creators to use the copious liquidity the Federal Reserve has provided. Indeed, it is doing everything to discourage job creation. Small wonder that the respondents to my own inquires and the NFIB and Duke University surveys are in "stall" or "Velcro" mode. The FOMC is doing everything it can to encourage the U.S. economy to steam forward. When we meet, we consider views that range from the most cautious perspectives on policy, such as my own, to the more accommodative recommendations of the well-known "doves" on the committee. We debate our different perspectives in the best tradition of civil discourse. Then, having vetted all points of view, we make a decision and act. If only the fiscal authorities could do the same! Instead, they fight, bicker and do nothing but sail about aimlessly, debauching the nation's income statement and balance sheet with spending programs they never figure out how to finance. I am tempted to draw upon the hackneyed comparison that likens our dissolute Congress to drunken sailors. But patriots among you might take umbrage, noting that a comparison with Congress in this case might be deemed an insult to drunken sailors. The Plea of the Navy Hymn and 'Illegitimum Non Carborundum'If you want to save our nation from financial disaster, may I suggest that rather than blame the Fed for being hyperactive, you devote your energy to getting our nation's fiscal authorities to do their job. Since 1879, every chapel service at the Naval Academy concludes with a hymn that contains the following plea: "O hear us when we cry for Thee, for those in peril on the sea." We cry for a nation that is in peril on the blustery seas of the economy. Our people are drowning in unemployment; our government is drowning in debt. You—the citizens and voters sitting in this room and elsewhere—are ultimately in command of the fleet that sails under the flag of the United States Congress. Demand that it performs its duty. Just recently, in a hearing before the Senate, your senator and my Harvard classmate, Chuck Schumer, told Chairman Bernanke, "You are the only game in town." I thought the chairman showed admirable restraint in his response. I would have immediately answered, "No, senator, you and your colleagues are the only game in town. For you and your colleagues, Democrat and Republican alike, have encumbered our nation with debt, sold our children down the river and sorely failed our nation. Sober up. Get your act together. Illegitimum non carborundum; get on with it. Sacrifice your political ambition for the good of our country—for the good of our children and grandchildren. For unless you do so, all the monetary policy accommodation the Federal Reserve can muster will be for naught." But, then again, I am not Ben Bernanke. And I imagine that after listening to me this evening, you might be grateful I am not. Now, in the great tradition of central banking, I will do my utmost to provide you with the "straight skinny" and avoid answering any questions you might have. Thank you. NotesThe views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.

| |

| Posted: 24 Sep 2012 07:00 AM PDT Morning reads to start off my week:

What are you reading?

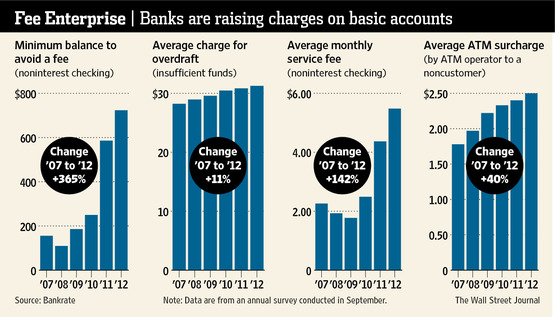

‘Free’ Checking Costs More | |

| Dark Pools: High-Speed Traders, A.I. Bandits, and the Threat to the Global Financial System Posted: 24 Sep 2012 06:00 AM PDT

Dark Pools is an up close account of the global stock market's subterranean battles and the rise of the "bots" — artificially intelligent systems that execute trades in milliseconds and use the cover of darkness to out-maneuver the humans who've created them. It is a fascinating story of how global markets have been hijacked by trading robots – many so self-directed that humans can't predict what they'll do next. And it shows how the new players moving into artificial intelligence are on the verge of tipping the entire system toward a global meltdown that could happen in minutes – maybe even seconds. I loved Scott Patterson’s first book, The Quants. Patterson will be speaking at TBP conference next month. Reviews:

Scott Patterson is a staff reporter at the Wall Street Journal, covering government regulation from the nation’s capital.

Source: Scott Patterson's Dark Pools: High-Speed Traders, A.I. Bandits, and the Threat to the Global Financial System | |

| QE Infinity and US Stock Market Posted: 24 Sep 2012 05:30 AM PDT QE Infinity and US Stock Market

"QE3+ is an operation analogous to walking a tightrope over Niagara Falls. Success will be exhilarating, but failure will be ugly." (John H. Makin. "The Fed Takes a Gamble." American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. September 2012.) The last two weeks have been remarkable in this new era of central banking. Developments continue. The latest move to withdraw more duration from the market is coming from the Bank of Japan (BOJ). The recently announced additional program by the BOJ includes a fifty-percent allocation to the purchase of ten-year Japanese government bonds. The other fifty percent will buy shorter-term government securities. Thus, the BOJ is applying half of its additional QE stimulus to extracting long duration from the government bond market, denominated in Japanese yen. In the US, we see the continuing evolution of QE3. The Federal Reserve is now increasing the outright purchase of longer-duration, federally backed mortgage securities. This is an extension of Operation Twist, whereby the Fed replaced short-term Treasury bills with longer-term Treasury notes and bonds. In the US, the amount of long duration extracted from the market is now estimated to rise to about $85 billion per month. In other words, approximately $1 trillion of long-duration US government securities will be purchased annually. By many estimates, that figure exceeds the amount of new, long-duration US government securities being created. The deficit of the US is financed by a combination of short-duration and long-duration instruments. Thus, the emphasis on long duration may mean that the total purchased could exceed the amount of actual new issuance of long-duration Treasuries. At the same time, the mortgage finance agencies, Fanny Mae and Freddie Mac, are limited in the amounts of credit they can extend. By some estimates, the Federal Reserve is in the process of becoming the largest government-sponsored enterprise involved in the financing of American housing. Whether all of this is good or bad, we do not know. The extraction from the market of long duration in this amount could lead to a very bullish outlook for the US stock market. We think that is now the case and will remain the case as long as the Fed policy continues in this direction. Assume that the short-term interest rate is going to be near zero for the next five to ten years. Assume that the long-term interest rate, defined by the ten-year Treasury note, is going to be in the vicinity of two percent for the next five to ten years. What would you then use as an equity-risk premium so you could calculate the value of the US stock market? Let's run some numbers to try to predict where the market is headed. A traditional equity-risk premium calculation would be 300 basis points over the riskless rate. If you apply the calculation to the short-term interest rate, the equity-risk premium would suggest (by traditional standards) an extraordinary price earnings multiple, because the benchmark short-term riskless rate is near zero. If you apply a more conservative approach and use the ten-year yield and a two percent estimate, you will derive an equity-risk premium comparative interest rate of about five percent. That is two percent on the riskless piece plus three percent on the equity risk premium, for a total of five. This calculation leads you to the basic conclusion that the stock market is priced properly and at an equilibrium level at twenty times earnings. Twenty times earnings is not excessive under this set of assumptions. The market would be neither cheap nor richly priced. Apply the twenty multiple to the earnings estimates that we have for 2013. Many estimates, which suggest that the US economy will slow down and flirt with recession in 2013, center at about $95 for the S&P 500 Index. Their range may be $90 low, high nineties high. Use $95 for this purpose. Estimates that are derived from the assumption that the US economy will continue with slow growth, a low rate of inflation, and a gradual but consistent recovery lead to an earnings estimate of about $105 for 2013. The wide range could be $90 low and $110 high, for an average of about $100. For the purpose of this counting exercise, I am going to use $90. Ninety times a PE of 20, which we derive from an equity-risk premium of 300 basis points over the ten-year Treasury yield, gives us an $1800 price target on the S&P 500 Index. That is the pricing of the stock market today, if the lower earnings number and a slower-growing economy are assumed and interest rates (as determined by the Federal Reserve in its current policy mode) remain stable. The Fed has essentially said it will hold these interest rates for a long period of time; and the slow-growth economic assumptions, outlined in deriving the value of the stock market, are consistent with the interest rates being so low for so long. Under these assumptions, 1800 on the S&P 500 Index is a fair price today. On previous occasions, we have written that our price target for the S&P 500 Index was 2000 by the end of this decade. Given the above assumptions, the policy broadcast by the Federal Reserve, and the elements that are in place to achieve it, we are raising that estimate. We think it is quite possible that the S&P 500 Index could be closer to 2300, 2400, or 2500 by the end of this decade. As long as Fed policy stays in its present mode, a little more inflation and a little pick-up in the growth rate during the course of the decade will let us easily achieve these numbers. Will the Fed stay in its present mode for that long? No one knows. Given the current concentration of intensity, effort, and communication on the employment situation in the US, you can easily guess that it will take four to seven years to achieve an unemployment rate low enough to warrant the Fed changing its policy stance. One Fed president has now called for continuation of this policy until the unemployment rate is 5.5 percent. Another Fed president has repeatedly called for this policy to continue until the unemployment rate falls below seven percent. The unemployment rate in the US today is above eight percent. Other employment statistics reveal that the employment situation in the US is not healthy and is not getting better very fast. For US stock market investors, these facts lead to only one conclusion: the bias has to be toward fully diversified investing in US stocks. Under the rationale that we will continue seeing the interest rates that we are accustomed to for a number of years, and that the policy will persist until the Fed can say it has achieved the goals established in its mandate to restore a baseline of full employment in the US, Cumberland Advisors' accounts will remain positioned as described in this commentary. ~~~ David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer, Cumberland, |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment