The Big Picture |

- A Hard Landing Down Under

- Will the BoJ increase its asset purchase programme next week

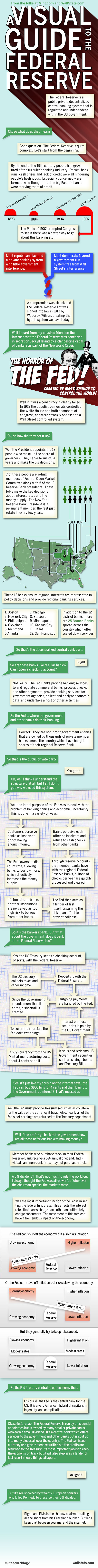

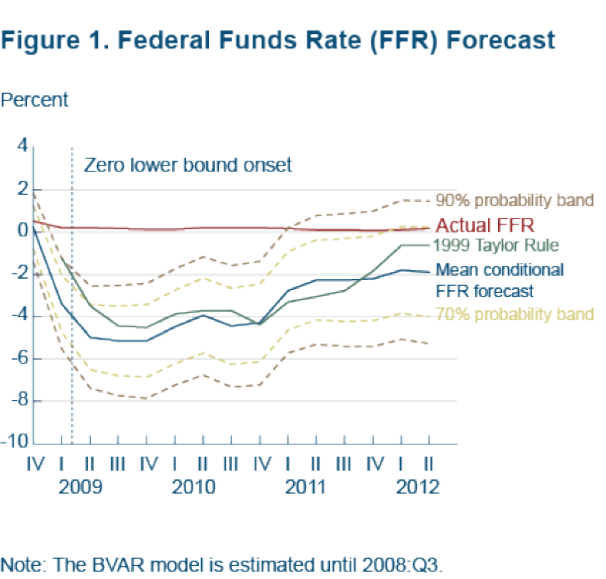

- Visual Guide To The Federal Reserve

- On Beauty

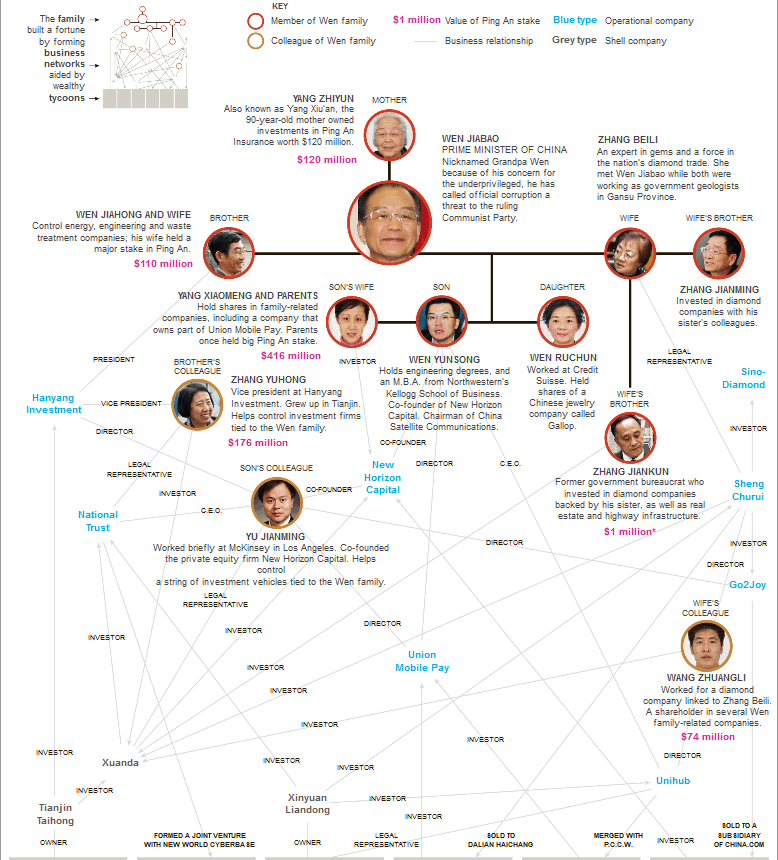

- The Wen Family Empire

- Rosie’s Rules to Remember (an Economist’s Dozen)

- Memo to Central Banks: You’re debasing more than our currency

- 10 Sunday Reads

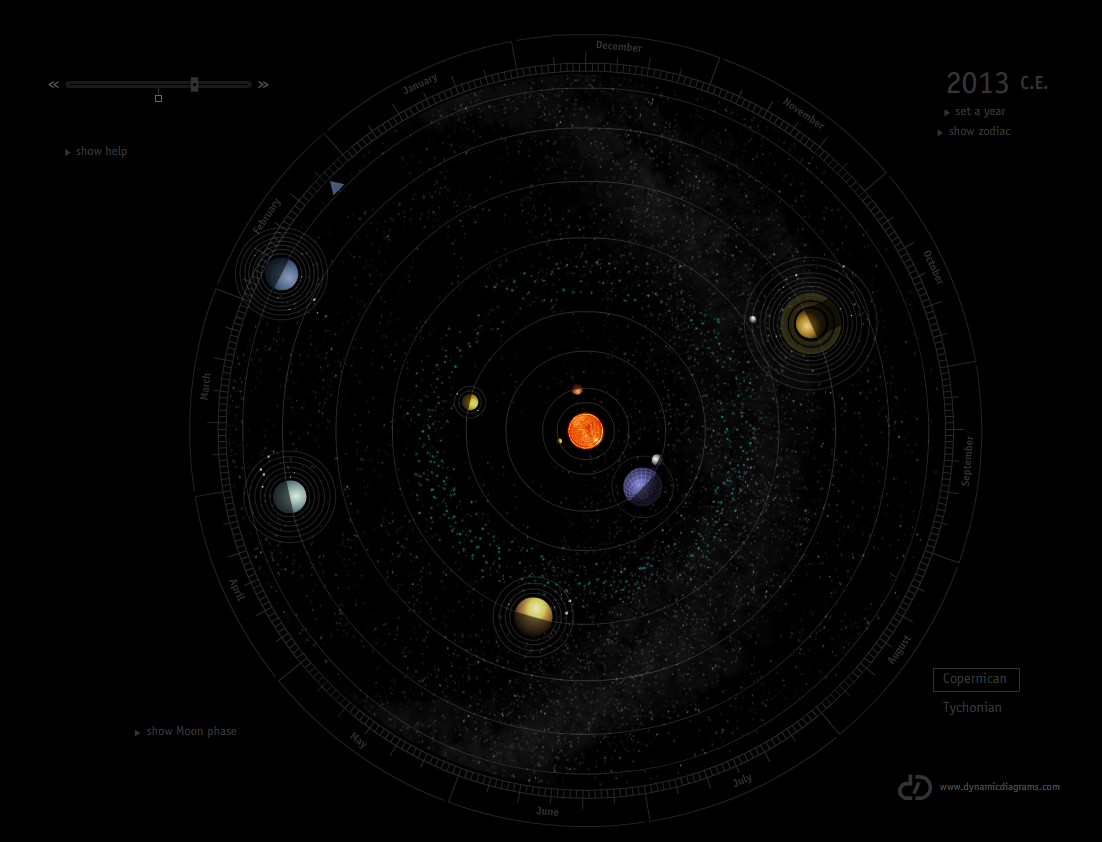

- Interactive Visualization of Simultaneous Planet Orbits

- Investing in Master Limited Partnerships: Risks and Opportunities

| Posted: 29 Oct 2012 03:00 AM PDT A Hard Landing Down Under

Australia’s bubble is built on China’s, and with no major stimulus in the offing, it may suffer a financial crisis in 2013

Mining has been a boom-bust industry throughout its history. The reason is the long development process of a mining asset. When demand pushes up prices for minerals, supplies take time to respond. Hence, prices can go very high in the initial phase of a demand boom. The eye-popping profitability draws all kinds of people into speculating for new mines, massively increasing the supply capacity years down the road. When the demand boom cools and prices decline, supply capacity keeps rising rapidly, which throws the industry into a depression with severe repercussions for its financiers. A decade ago, some Australian investors came to my office for advice on how to invest in China. I told them to go home and buy shares of Australian companies in the mining industry. Bellwether stocks like BHP have appreciated ten times since. The story began with China joining the WTO. This change would increase China’s share of global trade. As China’s expenditure is heavily weighed towards fixed-asset investment, this redistribution of income would increase the demand for mineral resources. Hence, I believed that the industry would have good times ahead. As the prices of minerals like iron ore surged, the super profitability attracted all sorts of people into prospecting all over the world. Numerous investors went into African jungles and Mongolian grassland to strike it rich. Even though risks for investing there very high, like getting one’s head chopped off by upset locals, the fantastic margins pumped up these people’s courage. Unfortunately, if and when these assets become productive, the margins are gone. Most stories about chasing riches in faraway lands end like this. Some smart people have sold undeveloped assets to others through IPOs in Hong Kong. Those who haven’t sold are stuck. ‘There Are Such Opportunities’ The market went from not believing in China’s growth story a decade ago to extrapolating past performance into the infinite future. In particular, China’s massive stimulus in 2008-09 that revived demand for commodities amid a global downturn convinced investors or speculators in this industry not to worry, i.e., China could do the same again if there was another downturn. As demand has weakened and prices collapsed, the faith in demand and prices coming back is surprisingly strong. That is why so many marginal projects continue to seek funding. The year 2008 should have been the end of this boom cycle. China’s stimulus misled the market into believing otherwise. China’s demand revival in 2009-10 was purely a governmental phenomenon. It piled more capacity formation on top of overcapacity. It merely postponed the inevitable adjustment and made it bigger. This is where the economy is now, paying for past mistakes. But the mining industry continues to believe and propagate the view that a big stimulus like in 2008 is coming. I recently attended a mining investor conference in Sydney. Australia has a vibrant market for prospecting. Anyone with claim over some unexplored land could list as a penny stock. The initial fund-raising could finance drilling costs. If drilling doesn’t come up with anything, the stock price goes to zero. If samples show promise, the stock price surges. The company can then raise more money to fund further studies. When the evidence for a viable mine surfaces, the company is sold to one of the big mining companies like BHP or Rio Tinto. This market is very efficient at motivating exploration and spreading risks around. It fires up the dream of “striking it rich.” In the conference, the story that got most attention was a penny stock just shot up 50 times in two months. The representatives from the company looked elated, proudly displaying shiny drilling samples. I met one lucky punter, a Chinese immigrant, who specializes in investing in such penny stocks. Through good research, he has picked more winners than losers. He recently spent millions of his winnings to buy a posh property close to the conference venue. “There are such opportunities in Australia,” he proudly told me. Bubble on a Bubble The Australian economy has boomed more than any other developed economy over the past decade. Its nominal GDP has doubled in a decade, and its currency value against the U.S. dollar has doubled too. As a result, its per capita income is much higher than in the United States or Europe. Its property is the most expensive among developed economies. The price of its main export, iron ore, appreciated ten times at its peak, which justified some of its prosperity. Foreign investment in its mining sector has played a more important role. It has caused the Australian dollar to appreciate strongly despite its current account deficit and higher inflation than elsewhere. The strong currency has attracted financial capital from retail investors in China and Japan. The snowball effect on the financial side has made the Australian economy strong despite the recent tumbling of the price of iron ore. As mentioned, the investment flow is sticky due to the long cycle of mining asset development. So much capital inflow has pumped up Australia’s monetary system, creating an environment of easy credit. This is the factor behind the real estate and consumption booms. If capital inflow is a bubble, Australia’s property market must be a bubble, too. When the capital inflow reverses, the bubble will pop. The Australian economy is probably a bubble on top of China’s overinvestment bubble. The latter’s unwinding will sooner or later trigger the former to do so, too. Among the mining investors I have met there is strong hope that China would soon introduce a stimulus like in 2008. This is why the price of iron ore has rebounded by 40 percent recently. Bottom fishers came in to speculate on China’s possible stimulus before or soon after the 18th Party Congress. They are likely to be disappointed. The last stimulus has made the overinvestment situation so severe that another round is just plain wrong. Also, it would trigger severe inflation and currency devaluation. I just don’t see it happening. Any foreign capital-inspired asset bubble bursts when the flow reverses. It causes the monetary system to contract. As the central bank replaces the outflow with new money, the currency value drops, which frightens Asian retail investors who hold Australian dollar deposits. Their flight causes the currency to tank more and liquidity to tighten. The property market will fall with the tightening liquidity and capital flight, which frightens away more foreign capital in the property market. The new equilibrium is defined by a much lower currency value and property price. In this new equilibrium, the currency value could be half of its peak value. The trigger will likely be a series of mining projects failing to obtain financing in the international capital market. Their investors will have to walk away from their investments. The reduced capital inflow makes the current account deficit more difficult to finance. Of course, a lower iron ore price increases the deficit too. The combination will cause the currency to establish a declining trend. The trend will send other financial capital to flee. Judging the timing of a bubble bursting is always an art. My gut feeling is that it happens in 2013. The global economy is sinking. This big picture makes the financing market jittery. When China’s stimulus fails to materialize in six months, many mining investors would walk. The Multiplier Effect On the way up a bubble has many ways to snowball. The same is true on the way down. When a currency is appreciating, there is strong demand for property. The strong property market powers credit-financed consumption. Australia has a highly developed capital market like in the United States. The multiplier effect is powerful on the way up. Debt has piled up in every corner of the economy, and creative accounting is employed to pump up banks’ balance sheets. One consequence is that Australia has the highest net foreign debt among all developed economies. On the way down people realize that they cannot spend borrowed money forever, and the assets on banks’ books are not worth as much as they say. What happened to the United States in 2008 could happen to Australia in 2013. Australia may suffer a full-blown financial crisis. We Never Learn Karl Marx said that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as a farce. Asset bubbles repeat themselves again and again, mocking mankind. People are so capable of suspending logic and believing in easy money, having a good time at no cost, and getting rich quick. When it all blows up, they blame somebody else, like the central bank for raising interest rates, government’s for tightening, short sellers, or somebody’s bad mouthing. They then ask for help, bailouts, or other assistance, even if they believe that the help would make things even worse eventually. The same will happen when Australia’s bubble bursts. This dynamic is now unfolding in China. Numerous speculators are stuck in property. Few people in China believe that another round of stimulus would do the country any good. But they still hope for another round because it could help them to unload their unsold properties or earn some quick money to pay off loan sharks. It feels painful now that some relief is desirable even if it kills you afterwards. But for everyone to unload, some stimulus must happen. Stimulus, when used repeatedly, loses its effectiveness because everyone wants to exit as soon as possible. The current round of monetary stimulus is only a month old. It is already losing traction. The global economy is sinking again. The odds are that the global economy is either near or in another recession already. When stimulus completely loses its effectiveness and just spews out bad stuff like inflation, people stop wanting it. Ben Bernanke tries to use stimulus to cover up the messes left behind by Alan Greenspan. When it completely stops working, someone like Paul Volcker will appear, telling people to suck it up. That day is not far away. The author is a board member of Rosetta Stone Capital Ltd.

|

| Will the BoJ increase its asset purchase programme next week Posted: 28 Oct 2012 04:00 PM PDT The impending US Presidential elections will remain the main focus over the coming 9 days. Intrade odds on President Obama winning have increased to 63.5%, well up from recent lows of around 55.0%. However, a number of analysts, with good historical track records of predicting the winner, continue to assert that Governor Romney will win. A number of polls report that Romney is ahead. The US NFP data next Friday will be an important data point – the forecast is for a modest 125k rise in non farm payrolls for October, with an increase in the unemployment rate to 7.9%, from a 3 year low of 7.8% last month; In Europe, the focus will be on Greece and Spain. The Germans are pressing to provide Greece with a 2 year extension (till 2016) to meet its budget deficit target of 3.0%. Mrs Merkel does not want a problem ahead of next September’s German general elections. She has become more confident that her coalition will support the changes to the existing terms, with the number of rebels decreasing. However, Greece continues to prevaricate and last Friday, finance minister Mr Schaeuble stated that he doubted that Greece had met all of its obligations proposed by the Troika. The head of the Greek Democratic Left party has rejected the labour reform measures proposed by the Troika and the Greek finance minister has stated that he wants the Greek parliament to sign off on the measures before he will accept them. Its typically Greek and the talks will go down to the wire – presumably Greece and the Troika will need to reach agreement ahead of the finance ministers meeting on the 13th November, though there is a meeting on 8th November to discuss the EU budget, where Greece may come up. Mrs Merkel may have arm twisted members of her coalition to agree to the 2 year extension (to 2016), but on Friday, the Dutch finance ministry stated that they would only accept an extension if it did not cost any more money. Well clearly an extension will cost more – up to E30bn. Mrs Merkel may even be able to pressurise the Dutch (and the Finns) to agree to the extension (its going to be hard), but Greece will want more money ahead of Mrs Merkel’s general election next September – that is going to be an impossible sell. The solution will probably be not only a 2 year extension to meet the budget deficit targets, but a loan repayment holiday and lower interest rates, if she can persuade her colleagues in the EZ. A haircut is not politically acceptable, though is inevitable in due course. In addition, Mr Asmussen of the ECB has suggested buying Greek bonds at a discount, thereby reducing its overall levels of debt – good idea, but it will not be enough. Yet more problems for the Finns (who have local elections today – the euro-sceptic Finn Party is expected to gain) and the Dutch, but Mrs Merkel unlike her colleague, Mr Schaeuble, is quite adamant and wants to delay the impending Greek default. Will this “cunning plan” work – given its the Greeks she is dealing with, almost certainly not in the medium to longer term, though a fudge in the short term is possible, with the likelihood that Greece will be given a reprieve. Whilst I have no doubt that the EU will also fudge any report they prepare, what of the IMF. The IMF are pushing for a write down of official sector loans to Greece, currently E125bn of the E325bn that Greece owes – certainly not going to be politically acceptable, especially at present , but is a certainty in due course. How does the IMF reconcile its views with that of the EU in the report they are preparing jointly with the EU and the ECB . Lying is not an option for them, whereas with the EU, well…………. Spain Prime Minister Rajoy continues to dither, as to whether to request a bail out or not. He would prefer to wait for the regional elections in Catalonia on 25th November, quite clearly. With his 2012 budget almost funded, he has a greater opportunity to, indeed, dither. However, bond yields are rising as the market begins to lose patience. Spanish 10 year yields rose by 28 bps last week. The head of Blackrock Mr Fink, stated that he expected Spain to request a bail out next week – the Euro surged on the news. I’m not sure how Mr Fink knows that as even the Spanish PM most likely does not – he remains firmly in dithering mode. Who knows when Mr Rajoy finally lets one of his colleagues ask for aid (I notice he has been away when Spain has a difficult issue to address/announce) – the only certainty is that it will happen fairly soon. Others With all the nonsense with Greece and Spain, Ireland is being shafted – quite ironic, as Ireland is the only country in the EZ (that has been bailed out) to have met its targets and will continue to do so. The EZ is back tracking on previous proposals to take a large element of debt (in respect of bailing out the Irish banks) off the nations balance sheet, having urged (indeed forced) them to do so. Ireland remains the only success for the EZ – if Irish politicians don’t understand how to play the game, well I suggest they learn fast and/or get advice. They are being well and truly shafted, though Mrs Merkel has admitted that Ireland is a “special case”. In addition, further austerity measures are going to go down like a lead balloon. The budget will increase taxes and reduce spending by E3.5bn. Ireland passed its 8th quarterly review of its bailout programme last week. If there is a resolution of any of the above, the Euro should rise. However, in the medium to longer term, I believe, quite firmly that the Euro will weaken materially. The recent EZ September M3 data shows a significant decline in credit – a clear warning sign. If this continues and I expect it to do so, the ECB will have no choice but to embark on outright QE , rather than on sterilised QE , as currently proposed. However, its one step at a time with Draghi and he has to convince his German paymasters. Clearly the time is not right to do so, especially as inflation is above the 2.0% target, established by the ECB. However, interestingly, Draghi advised German politicians last Thursday that deflation, rather than inflation was going to be a problem for a number of EZ countries, thereby taking the 1st step towards preparing them for unsterilised QE – most likely in the 1st/2nd Q next year – clearly bullish for the markets. In addition, it is clear that the fiscal multiplier for Portugal is above 1.0, some suggest 1.5. Spain, arguably, could well be higher given its banking problems. That should tell the good and the great that further austerity measures in these countries will just aggravate the situation even further. Remember, the negative impact of the fiscal multiplier is worse when interest rates are near zero and when other countries are also implementing austerity measures. These policies are completely crazy given the present situation and are way beyond their sell by date – personally I believe that they will have to be changed within 3 to 6 months time; Just a few other points. The COT reports that a net short speculative position (-18.2k, as opposed to a long +10.1 in the previous week) has been established in the Yen last week, for the 1st time in 4 months – traders believe that the BoJ will increase its asset purchase programme (Yen10tr expected, though has been priced in, most likely) at its meeting on the 30th October. In addition, the BoJ is likely to tweak its wording in respect of its inflation target – may change the wording to an inflation goal, rather than an inflation target, especially as inflation is expected to remain below 1.0% for the next 2 years. Japan has suffered from deflation for some 20 years. The BoJ will report on its outlook for GDP growth and inflation for the fiscal year beginning in April 2014 at next weeks meeting. I remain short the Yen, against the US$. The BoJ has consistently disappointed, but the situation is now getting to more than a critical level and something will have to be done imminently; Mr Ishihara, the governor of Tokyo, has resigned and is to run for a seat in Parliament. Mr Ishihara created the recent spat with China over the disputed islands by initiating the purchase of the islands from its private owner. The dispute with China is likely to lead to a more right wing and nationalist government in Japan, following the elections, which are being demanded by opposition parties and who have refused to vote for measures to increase borrowings by the government. The current administration has about 1 month to end the deadlock. The current PM, Mr Noda, is trying to delay elections, which must be called before the term of the lower house expires in August next year. Japan’s neutrality position may well be changed following an election, raising tensions in the region even further, especially with China. Mr Ishihara is likely to team up with Mr Hashimoto, the populist Osaka Mayor, who leads the new but increasingly popular Japan Restoration Party; A number of Indian ministers have resigned, with new ministers appointed for foreign affairs, power, oil, rail, law and commerce today. The Indian PM is trying to clean up his act, following numerous corruption scandals. Notably, Rahul Gandhi was not appointed as a minister, as was widely speculated. The newly appointed finance minister has pressed ahead with reforms. The attitude has changed, with investors more positive on India. Its now necessary to implement to proposals that have been announced. The next general elections in India will have to held before May 2014; Mr Berlusconi, recently found guilty of tax fraud and sentenced to 1 year in prison (he will not go to prison, though he faces additional charges of having sex with a minor) states that he will withdraw support for Mr Monti by calling for a vote of no confidence, which will result in elections in Italy ahead of time – elections were expected in March/April next year. The court has also banned Mr Berlusconi from holding public office for 5 years and from holding a corporate position for 3 years. Mr Belusconi has stated that he will not stand for PM. Mr Belusconi’s TV statement was designed to shore up support for his party, which has declined materially – a recent poll reports that it stands at just 14%. More political uncertainty in Italy is not what the country needs – economic data recently has been slightly more positive; In case you think its all calm in the EZ, just listen to Mr Schaeuble. He stated last week that “I’m not so sure that the worst of the crisis (in the EZ) is behind us”. Hmmmm; The market has ignored the downgrades of the largest French banks (including, BNP, Soc Gen and Credit Agricole) by S&P – dangerous. What’s more, the reason given was the deteriorating economic environment in France, including a likely decline in property prices. No guesses for what that means – the only question is whether the other agencies downgrade France by just 1 notch? – S&P downgraded France in January. Timing, early next year, I would guess – a 1st Q event? Maybe a good time for the ECB to announce unsterilised QE to compensate; As usual, volatile markets, but hey, what do you want – a quiet life. Have a great weekend. Kiron Sarkar 28th October 2012 |

| Visual Guide To The Federal Reserve Posted: 28 Oct 2012 12:00 PM PDT |

| Posted: 28 Oct 2012 11:15 AM PDT Eric Reiss and me in the Day One Closing Plenary at EuroIA 2012, Rome. Cue piano music in the background.

On Beauty from Andrea Resmini |

| Posted: 28 Oct 2012 11:00 AM PDT |

| Rosie’s Rules to Remember (an Economist’s Dozen) Posted: 28 Oct 2012 09:00 AM PDT Yet another rule to add to our ongoing collection. This one comes from Economist David Rosenberg, formerly Merrill Lynch’s chief dismal scientist, now at Gluskin Sheff:

Source: |

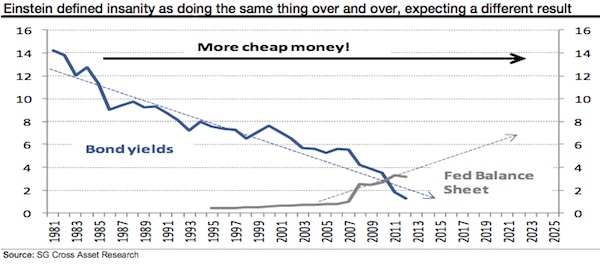

| Memo to Central Banks: You’re debasing more than our currency Posted: 28 Oct 2012 05:30 AM PDT Memo to Central Banks: You're debasing more than our currency

I can only pass on Societe Generale's work to you once in a while, but the piece for today's Outside the Box is important enough that its author, Dylan Grice, worked hard to convince his bosses to let me share it with you. Dylan is one of my favorite investments analysts, as well as just an all-around nice guy.

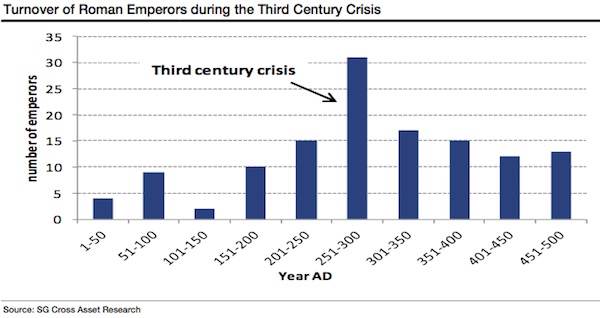

In a change from his usual fun-loving demeanor, Dylan issues a serious warning here. I am more worried than I have ever been about the clouds gathering today (which may be the most wonderful contrary indicator you could hope for…). I hope they pass without breaking, but I fear the defining feature of coming decades will be a Great Disorder of the sort which has defined past epochs and scarred whole generations…. So I keep wondering to myself, do our money-printing central banks and their cheerleaders understand the full consequences of the monetary debasement they continue to engineer? He runs through some of the Great Debasements of the past, starting with third-century Rome, running through Europe's medieval inflations and the French Revolution, to the monetary horror story of Weimar Germany in the 1920s. His key point is that inflations and hyperinflations don't just hurt money, they hurt people and the societies they live in. Inflating money is less trustworthy money, and so people doing business trust each other less. Plus, those who are farthest from the source of artificially created money suffer the most (the "Cantillon effect"). And now the social debasement is clear for all to see. The 99% blame the 1%, the 1% blame the 47%, the private sector blames the public sector, the public sector returns the sentiment … the young blame the old, everyone blame the rich … yet few question the ideas behind government or central banks … I'd feel a whole lot better if central banks stopped playing games with money…. All I see is more of the same – more money debasement, more unintended consequences and more social disorder. Since I worry that it will be Great Disorder, I remain very bullish on safe havens. In just 10 days we will see how the US elections turn out. Depending on what happens after, the US will either remain as one of those safe havens (and perhaps become even more of one) or those of us who reside here will need to start thinking more globally. I know a lot of thoughtful people who are already contemplating (if not acting on) plans to make sure their life savings maintain their buying power through the coming decade. I remain optimistic that we will set ourselves on a course that ends in a safe harbor, although the sailing will be quite volatile. What Dylan describes are the unintended consequences of people who think they understand macroeconomics and who are well-intentioned but whose policies can be most disruptive. Sunday night I head for South America. I always enjoy traveling there, and I am interested to see what I can learn, both about how Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina are doing and what they are thinking when they look north. I really do find that I learn much more than I impart on these trips. Election night will find me in a bar drinking non-alcoholic beer in Cafayete in the far north of Argentina, where the California polls won't close till almost midnight. It might be a long night. Maybe I can set up a twitter account from there. Might be fun. There will be lots of friends on hand to share the times and commentary. I will be back in Texas that Sunday to write my letter, and I'll be thinking about how the results will impact all of us everywhere. Have a great weekend. And I am off to cast my absentee ballot! You make sure to vote too! Your wishing I was in Illinois so I could vote several times analyst, John Mauldin, Editor subscribers@mauldineconomics.com Popular Delusions By Dylan Grice, Societe Generale At its most fundamental level, economic activity is no more than an exchange between strangers. It depends, therefore, on a degree of trust between strangers. Since money is the agent of exchange, it is the agent of trust. Debasing money therefore debases trust. History is replete with Great Disorders in which social cohesion has been undermined by currency debasements. The multi-decade credit inflation can now be seen to have had similarly corrosive effects. Yet central banks continue down the same route. The writing is on the wall. Further debasement of money will cause further debasement of society. I fear a Great Disorder. I am more worried than I have ever been about the clouds gathering today (which may be the most wonderful contrary indicator you could hope for…). I hope they pass without breaking, but I fear the defining feature of coming decades will be a Great Disorder of the sort which has defined past epochs and scarred whole generations. "Next to language, money is the most important medium through which modern societies communicate" writes Bernd Widdig in his masterful analysis of Germany's inflation crisis "Culture and Inflation in Weimar Germany." His may be an abstract observation, but it has the commendable merit of being true … all economic activity requires the cooperation of strangers and therefore, a degree of trust between cooperating strangers. Since money is the agent of such mutual trust, debasing money implies debasing the trust upon which social cohesion rests. So I keep wondering to myself, do our money-printing central banks and their cheerleaders understand the full consequences of the monetary debasement they continue to engineer? Inflation of the CPI might be a consequence both seen and measurable. A broad inflation of asset prices might be a consequence seen, though not measurable. But what about the consequences that are unseen but unmeasurable – and are all the more destructive for it? I feel queasy about the enthusiasm with which our wise economists play games with something about which we have such a poor understanding.

If you take a look around you, any artefact you see will only be there thanks to the cooperative behaviour of lots of people you don't know. You will probably never know them, nor they you. The screen you watch on your terminal, the content you read, the orders which make the prices flicker … the coffee you drink, the cup you hold, the bin you throw it in afterwards … all your clothes, all your accessories, all the buildings you've been in, all the cars … you get the idea. Without exception everything you own, everything you want to own, everything you need, and everything you think you need embodies the different skills and talents of a mind-boggling number of complete strangers. In a very real sense we constantly trust in strangers to a degree, as strangers trust us. Such cooperative activity is to everyone's great benefit and I find it is a marvellous thing to behold. The value strangers put on each other's contributions manifests itself in prices, and prices require money. So it is through money that we express the extent of our appreciation for the many different talents embedded in each thing we consume, and through money that our skills are in turn valued by others. Money, in other words, is the agent of this anonymous exchange, and therefore money is also the agent of the hidden trust on which it depends. Thus, as Bernd Widdig reflects in his book (which I urge you all to read), money … "… is more than simply a tool for economic exchange; its different qualities shape the way modern people think, how they make sense of their reality, how they communicate, and ultimately how they find their place and identity in a modern environment." Debasing money might be expected to have effects beyond the merely financial domain. Of course, there are many ways to debase money. Coin can be clipped, paper money can be printed, credit can be created on the basis of demand deposits which aren't there … the effects are ultimately the same though: the implied trust that money communicates through society is eroded. To see how, consider the example of money printing by authorities. We know that such an exercise raises revenues since the authorities now have a very real increase in purchasing power. But we also know that revenue cannot be raised by one party without another party paying. So who pays? If the authorities raise taxes explicitly and openly, voters know exactly why they have less spending power. They also know how much less spending power they have. But if the authorities instead raise money by simply printing it, they raise the revenue by stealth. No one knows upon whom the burden falls. People notice only that they can't afford the things they used to be able to afford, or they can't afford the things which everyone else can afford. They know that something is wrong, but they just don't know what, why, or who is to blame. So inevitably they look for someone to blame.

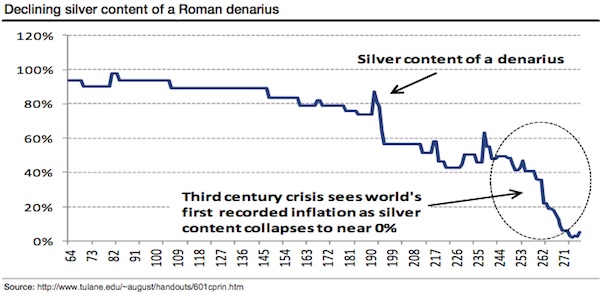

The dynamic is similar to that found in the well-worn plot line in which a group of strangers are initially brought together in happier circumstances, such as a cruise, a long train journey or a weekend away. In the beginning, spirits are high. The strangers exchange jokes and get to know one another as the journey begins. Then some crime is committed. They know it must be one of them, but they don't know who. A great suspicion ensues. All trust between them is broken down and the infighting begins…. So it is with monetary debasement, as Keynes understood deeply (so deeply, in fact, that it's ironic so many of today's crude Keynesians support QE so enthusiastically). In 1921 he said: "By a continuing process of inflation, Governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some …. Those to whom the system brings windfalls …. become "profiteers" who are the object of the hatred … the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery .. Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose." History is replete with Great Disorders in which currency debasement has coincided with social infighting and scapegoating. I have written in the past about the Roman inflation of the Third Century AD. The following chart shows the rapid turnover of emperors during what is known as the Third Century Crisis. As trade declined, crops failed and the military suffered what must have seemed like constant defeat, it wasn't difficult for a successful or even popular general to convince the rest of the empire that he'd make a better fist of governing.

But this political turnover was accompanied by what may be history's first recorded instance of systematic currency debasement. With the empire no longer expanding and barbarians being forced westwards by the migrations of the Steppe peoples, Rome's borders were under threat. But the money required to fund defence wasn't there. Successive emperors therefore reached the same conclusions that kings, princes, tyrants and democratically elected governments would later reach down the ages when faced with a perceived "shortage of money": they created more by debasing the existing stock. In the second half of the third century, the silver content of a denarius had shrunk to zero. Copper coins disappeared altogether. This debasement of currency also coincided with a debasement of society. Factions grew more suspicious of one another. Communities fragmented. And one part of the community bore the brunt of the fears: Christians. While Rome had always welcomed new religions and Gods, incorporating new foreign deities as their empire grew, Christians were altogether different. They rejected Rome's gods. They refused to pray to them. They said that only their God was deserving of worship. The rest of the Romans concluded that this obstinacy must be a source of great anger for their own ancient Roman gods, and supposed that those gods must now be exacting their own great punishment in return.

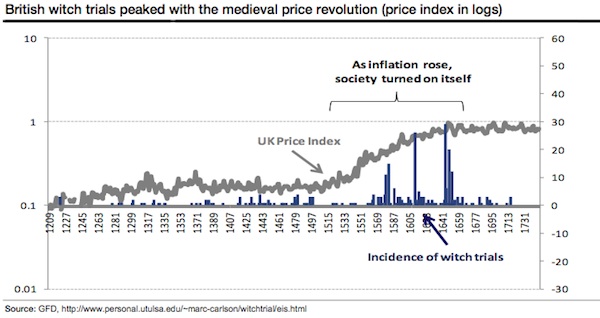

So the Romans turned on their Christians with a great violence which lasted throughout the period of the currency debasement but peaked with Diocletian's edict of 303 AD. The edict decreed, among other things, that Christian meeting places be destroyed, Christians holding office be stripped of that office, Christian freedmen be made slaves once more and all scriptures be destroyed. Diocletian's earlier edict, of 301 AD, sought to regulate prices and set out punishments for 'profiteers' whose prices deviated from those set out in the edict. A similar dynamic seems evident during Europe's medieval inflations, only now, the confused and vain effort to make sense of the enveloping turmoil saw the blame focus on suspected witches. The following chart shows the UK price index over the period with the incidence of witchcraft trials. Note the peak in trials coinciding with the peak of the price revolution.

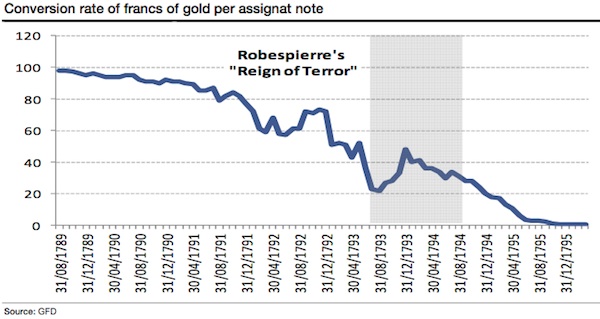

Were the same dynamics at work during the French Revolution of 1789? The narrative of Madame Guillotine and her bloody role is well known. However, the execution of royalty by the Paris Commune didn't begin until 1792, and the Reign of Terror in which Robespierre's Orwellian sounding "Committee of Public Safety" slaughtered 17,000 nobles and counter-revolutionaries didn't start until well into 1793. In the words of guillotined revolutionary Georges Danton, this is when the French revolution "ate itself". But the coincidence of these events to the monetary debasement is striking. The political violence was justified in part by blaming nobles and counter-revolutionaries for galloping inflation in food prices. It saw 'speculators' banned from trading gold, and prices for firewood, coal and grain became subject to strict controls. According to Andrew Dickson White, author of "Fiat Money Inflation in France", (echoing Keynes' remark that "wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery") "economic calculation gave way to feverish speculation across the country."

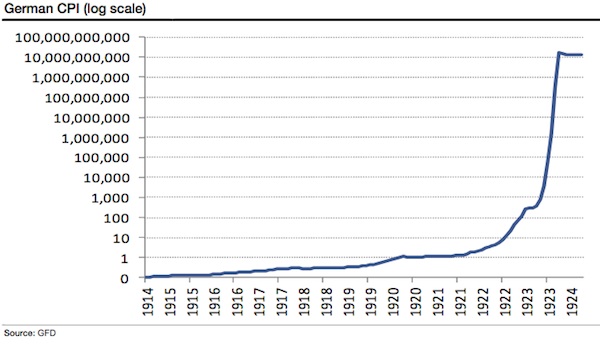

However, the most tragic of all the inflations in my opinion, and certainly the starkest example of a society turning on itself was the German hyperinflation. Its causes are well known. Morally and financially bankrupt by the First World War, the reparation demands of the Allies (which Keynes argued vociferously against) followed by the French occupation of the Ruhr served to humiliate a once-mighty nation, already on its knees. And it really was on its knees. Germany simply had no way to pay. The revolution following the flight of the Kaiser was incomplete. Concern was widespread that Germany would follow the path blazed by Moscow's Bolsheviks only a year earlier. A de facto civil war was being fought on the streets of major cities between extremist mobs of the left and right. Six million veterans newly demobilized, demoralized, dazed and without work were unable to support their families … the great political need was to pay off the "internal debts" of pensions, life insurance and welfare support in any way possible. The risk of printing whatever was required was well understood. Bernhard Dernberg, vice chancellor in 1919, found himself overwhelmed with promises to pay for the war disabled, food subsidies, unemployment insurance, etc., but everyone knew where the money was coming from: "A decision of the National Assembly is made. On its basis, Reich Treasury bills are printed and on the basis of the Reich Treasury bills, notes are printed. That is our money. The result is that we have a pure assignat economy." But print they did. Prices would rise by a factor of one trillion. At the end of the war, Germany owed 154bn Reichmarks to its creditors. By November 1923, that sum measured in 1914 purchasing power was worth only 15 pfennigs.

It is difficult to comprehend the psychological trauma inflicted by this episode. Inflation inverted the efficacy of correct behaviour. It turned the ethics of thrift, frugality and notions such as working hard today to bring benefit tomorrow completely on their heads. Why work today when your rewards would mean nothing tomorrow? What use thrift and saving? Why not just borrow in depreciating currency? Those who had worked and saved all their lives, done everything correctly and invested what they had been told was safe, were mercilessly punished for their trust in established principles, and their inability to see the danger coming. Those with no such faith who had seen the danger coming had benefited handsomely. Everything, in other words, was dependent on one's ability to speculate, recalling what Dickson White observed of the French Revolution and Keynes reflections more generally. Erich Remarque is best known for his anti-war novel "All Quiet on the Western Front" but perhaps his best work was the "The Black Obelisk" set in the early Weimar period, and a penetrating meditation on the upside-down world of inflation. The protagonist Georg poignantly captures this speculative imperative when he sits down and lets out a long sigh: "Thank God that it's Sunday tomorrow … there are no rates of exchange for the dollar. Inflation stops for one day of the week. That was surely not God's intention when he created Sunday." Perhaps the most eloquent chronicler of the Weimar hyperinflation was Elias Canetti, whose mother moved him from the security of Zurich to Frankfurt in 1921 to take advantage of cheaper living. Canetti never forgave her, and his life's work shows what a lasting impression the move from heaven to hell made: "A man who has been accustomed to rely on (the monetary value of the mark) cannot help feeling its degradation as his own. He has identified himself with it for too long, and his confidence in it has been like his confidence in himself … Whatever he is or was, like the million he always wanted, he becomes nothing" More tragic still was what German society became during the inflation. Like other Axis countries on the wrong side of the War and now in the grip of hyperinflation, Germany turned viciously on its Jews. It blamed them for the surrounding evil as Romans had blamed Christians, medieval Europeans had suspected witches, and French revolutionaries had blamed the nobility during previous inflations. In his classic "Crowds and Power", Canetti attributed the horror of National Socialism directly to a "morbid re-enaction impulse". "No one ever forgets a sudden depreciation of himself, for it is too painful … The natural tendency afterwards is to find something which is worth even less than oneself, which one can despise as one was despised oneself. It is not enough to take over an old contempt and to maintain it at the same level. What is wanted is a dynamic process of humiliation Something must be treated in such a way that it becomes worth less and less, as the unit of money did during the inflation. And this process must be continued until its object is reduced to a state of utter worthlessness. … In its treatment of the Jews, National Socialism repeated the process of inflation with great precision. First they were attacked as wicked and dangerous., as enemies; then, there not being enough in Germany itself, those in the conquered territories were gathered in; and finally they were treated literally as vermin, to be destroyed with impunity by the million. All this is very disturbing stuff, but testament to a relationship between currency devaluation and social devaluation. Mine is not a complete or in any way rigorous analysis, I know. I emphasize that it's not in any way meant as some sort of crude mapping on to today's environment. My point is to show that money operates in many social domains beyond the financial, and that tying currency devaluation to social devaluation might have some merit. Consider some recent and less extreme currency inflations. The 1970s bear market in equities saw relatively mild inflation which was also characterized by relatively mild but nevertheless real factionalization of society. An ideological left vs right battle played out between labour and capital, unions and non-unions and perhaps most bizarrely, between rock and disco. As already stated, money implies a trust in the future. It implies that today's money can be used in the future. So in the era of punk, did the Sex Pistols provide the most concise commentary of the malaise?

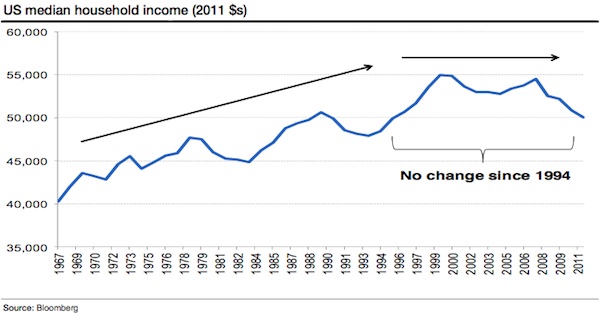

Which brings us to today. Despite the CPI inflation of the 1970s receding, our central banks have continued to play games with money. We've since lived through what might be the largest credit inflation in financial history, a credit hyperinflation. Where has it left us? Median US household incomes have been stagnant for the best part of twenty years (chart below)

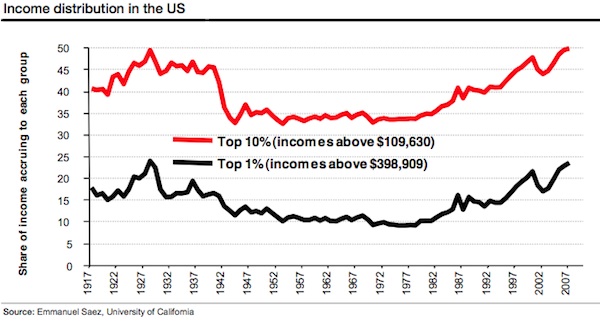

Yet inequality has surged. While a record number of Americans are on food stamps, the top 1% of income earners are taking a larger share of total income than since the peak of the 1920s credit inflation. Moreover, the growth in that share has coincided almost exactly with the more recent credit inflation. These phenomena are inflation's hallmarks. In the Keynes quote above, he alludes to the "artificial and iniquitous redistribution of wealth" inflation imposes on society without being specific. What actually happens is that artificially created money redistributes wealth towards those closest to it, to the detriment of those furthest away.

Richard Cantillon (writing decades before Adam Smith) was the first to observe this effect (hence "Cantillon effect"). He showed how those closest to the money source benefited unfairly at the expense of others, by thinking through the effects in Spain and Portugal of the influx of gold from the new world as follows: "If the increase of actual money comes from mines of gold or silver … the owner of these mines, the adventurers, the smelters, refiners, and all the other workers will increase their expenditures in proportion to their gains. . . . All this increase of expenditures in meat, wine, wool, etc. diminishes of necessity the share of the other inhabitants of the state who do not participate at first in the wealth of the mines in question. The altercations of the market, or the demand for meat, wine, wool, etc. being more intense than usual, will not fail to raise their prices … Those then who will suffer from this dearness … will be first of all the landowners, during the term of their leases, then their domestic servants and all the workmen or fixed wage-earners … All these must diminish their expenditure in proportion to the new consumption … (Quoted in Mark Thornton, "Cantillon on the Cause of the Business Cycle" Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics Vol 9, No 3 [Fall 2006]) In other words, the beneficiaries of newly created money spend that money and bid up the price of goods with their higher demand. Those who suffer are those who have to pay newly higher prices but did not benefit from the newly created money. The credit inflation analog to the Cantillon effect has played out perfectly in recent decades. Central banks provided cheap money to banks, the cheap money artificially inflated asset prices, artificially inflated asset prices made anyone connected to those assets rich as we became a nation of speculators, those riches were achieved at everyone else's expense, and 'everyone else' has now realized what has happened and is understandable enraged … as Keynes explained, "Those to whom the system brings windfalls …. are the object of the hatred. And now the social debasement is clear for all to see. The 99% blame the 1%, the 1% blame the 47%, the private sector blames the public sector, the public sector returns the sentiment … the young blame the old, everyone blame the rich … yet few question the ideas behind government or central banks …

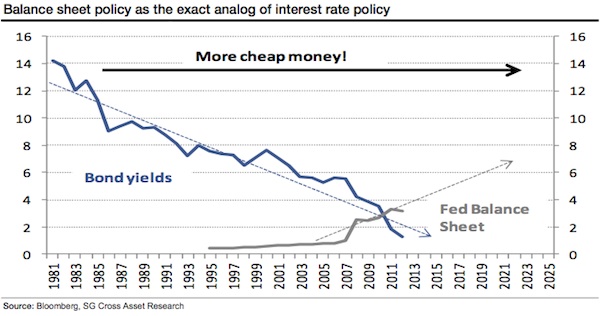

I'd feel a whole lot better if central banks stopped playing games with money. But I can't see that happening anytime soon. The ECB has thrown the towel in, following the SNB last year in committing effectively to print unlimited amounts of money for the greater good. The BoE and the Fed have long since made a virtue of what was once considered a necessity, with what was once the unconventional conventional. As James Bullard told everyone a few weeks before the last Fed meeting, lest there be any doubt: “Markets have this idea that, there’s QE1 and QE2, so QE3 must be the same as those previous ones. It’s not that clear to me that this is the way this is going … it would just be to do balance sheet policy as the exact analogue of interest rate policy.” In other words, the central banks' balance sheets are the new policy tool. As interest rates embarked on a multi-year decline from the 1980s on, central bank balance sheets are set to embark on a multi-year climb …

So as Nobel Prize winning experts in economics punch the air because inflation expectations have been rising since the policy was announced, "It's the whole point of the exercise" (Duh!) the BoE admits that QE has mainly benefited the rich, but vows to continue anyway. All I see is more of the same – more money debasement, more unintended consequences and more social disorder. Since I worry that it will be Great Disorder, I remain very bullish on safe havens. The next few issues of Popular Delusions will outline some thoughts on what exactly that means.

|

| Posted: 28 Oct 2012 05:00 AM PDT Some reads to start your Sunday morning:

What are you reading?

|

| Interactive Visualization of Simultaneous Planet Orbits Posted: 28 Oct 2012 05:00 AM PDT |

| Investing in Master Limited Partnerships: Risks and Opportunities Posted: 28 Oct 2012 03:00 AM PDT |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment