The Big Picture |

- QE Auctions of Treasury Bonds

- 10 Monday PM Reads

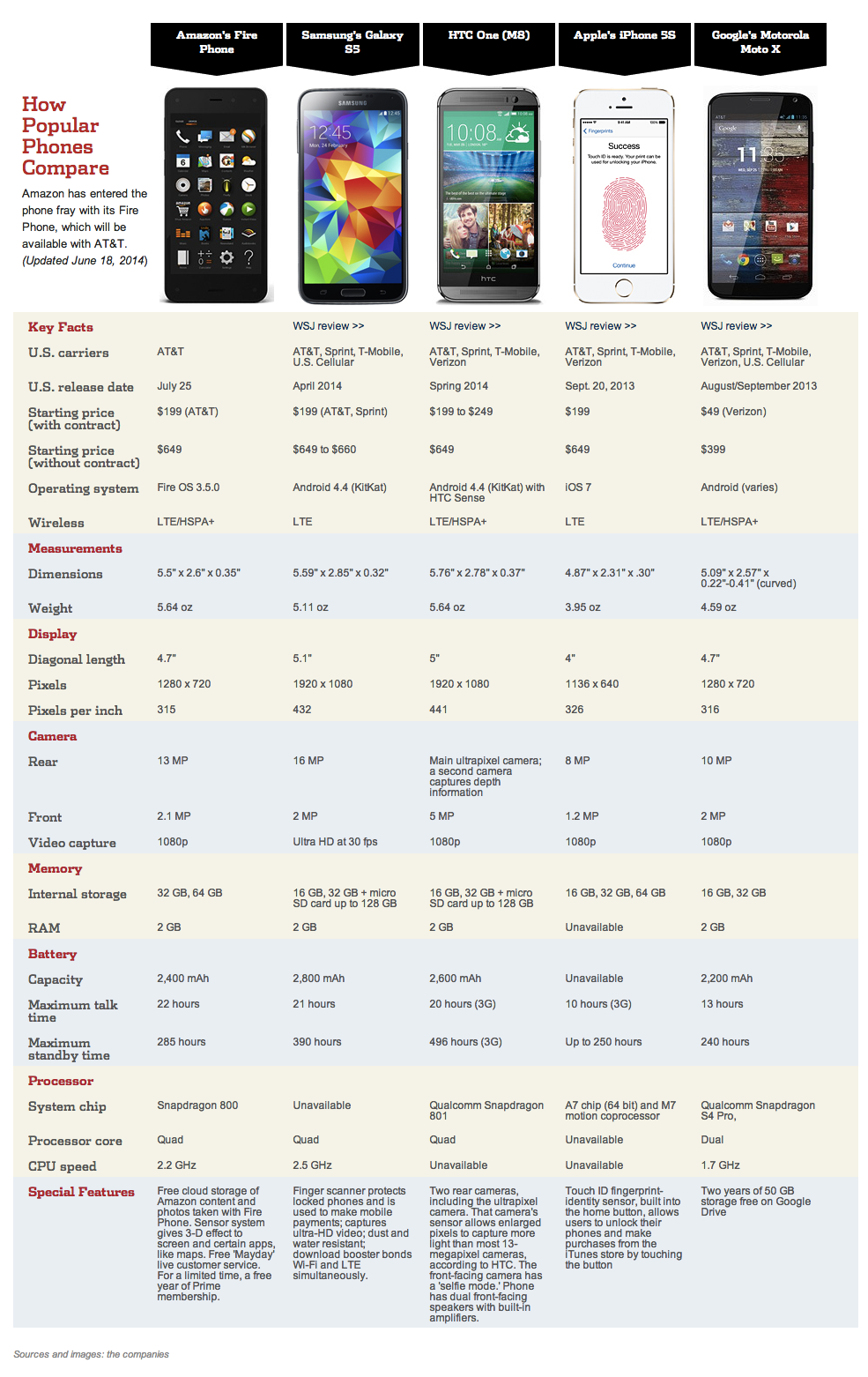

- Amazon Fire Phone Review: Full of Gimmicks, Lacking Basics

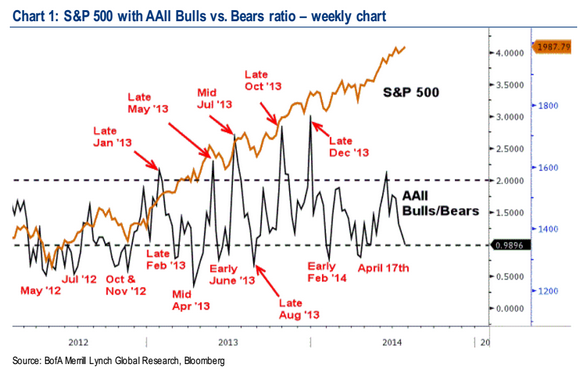

- Where Did All the Bulls Go?

- Rising Rates Unliklely to Kill This Bull Market

- 10 Monday AM Reads

- My Interview with SEC Chair Arthur Levitt on Soundcloud

- Kotok Interview with ETF.com

| Posted: 29 Jul 2014 02:00 AM PDT |

| Posted: 28 Jul 2014 01:30 PM PDT My afternoon train reads:

What are you reading?

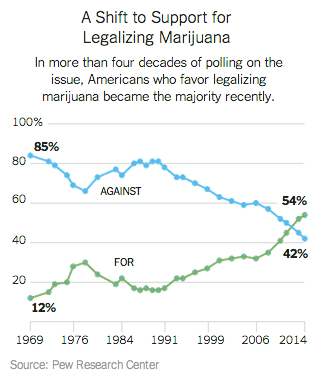

The Public Lightens Up on Marijuana

|

| Amazon Fire Phone Review: Full of Gimmicks, Lacking Basics Posted: 28 Jul 2014 11:30 AM PDT

|

| Posted: 28 Jul 2014 09:30 AM PDT |

| Rising Rates Unliklely to Kill This Bull Market Posted: 28 Jul 2014 06:30 AM PDT One of the oldest rules on Wall Street is, don't fight the Fed. When the Federal Reserve is cutting rates, you want to be long equities, and when it is tightening, get out of the way. This has been a cause for concern since the Fed began talking of tapering its program of quantitative easing and ending its zero interest-rate policy. But the knee-jerk response to an over-simplified rule of thumb might be wrong. When we look at the actual data — what happens to stocks when rates rise — we find a very different set of results than this heuristic suggests. Before I get to the numbers let’s look at both the positive and negative sides of increasing rates. It is understandable that there is concern with a rising-rate environment. Often, higher rates signal an overheating economy, higher costs of credit to purchase goods and services and a potential profit squeeze as operating expenses rise. When the Fed is in its inflation-fighting mode, too much tightening will cause a recession. However, there are also positives to increasing interest rates. Rates are merely the price of capital. Higher demand for capital means the economy is strengthening, as consumers borrow to spend on goods and to buy homes and companies seek to hire and do more investment spending. Higher rates also mean the risk of deflation is decreasing. Lastly, it reflects a normalization of Fed interventions, which today would suggest that the credit crisis is behind us.

|

| Posted: 28 Jul 2014 06:00 AM PDT My morning train reads (continues here):

|

| My Interview with SEC Chair Arthur Levitt on Soundcloud Posted: 28 Jul 2014 05:00 AM PDT Check out this fascinating and freewheeling interview with former SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt:

|

| Posted: 28 Jul 2014 03:00 AM PDT An Interview with ETF.com

We are forwarding an interview done with ETF.com. We thank them for permission to share it with our readers. Dennis Hudachek of ETF.com was kind enough to spend considerable time in this interview and to capture the comments quite accurately. Any errors are mine alone. Please note that the revised and second edition of the book "From Bear to Bull with ETF's" will be released within the next ten days. Our conclusions articulated in this interview are unchanged from when it occurred. We still have a significant cash reserve. David Kotok, July 25, 2014

David Kotok is the chairman and chief investment officer of Cumberland Advisors, a registered investment advisory firm based in Sarasota, Fla. Cumberland offers several fixed-income, equity and balanced portfolios, with its equity portfolios constructed using solely ETFs. He is a frequent guest on various financial television networks, and is quoted regularly in the financial press. Kotok has authored two books, including “From Bear to Bull with ETFs”; a second edition of the book is due for release in the coming weeks. Kotok recently sat down with ETF.com to give us the latest on Puerto Rico and its potential implications in the municipal bonds market. He discusses high-yield debt and gives us his current favorite fixed-income and equity plays. ETF.com: Puerto Rico passed a law in late June whereby municipalities can now declare bankruptcy. Would you give us the latest there, including your take on all this? There’s an intricacy here that has to do with the government development bank, because there’s an intertwined relationship between all of the Puerto Rico agencies and the government itself, and the government development bank. How this all plays out in terms of reorganizing, restructuring the priority of claims in a reorganization remains to be seen. I believe approximately $20 billion worth—out of the $70 billion or so Puerto Rico debt—is impacted by this law change. The law change is currently being litigated by institutional holders of the $20 billion. The strongest of those institutional holders are mutual funds that have the debt to contest the decision, and the bond insurers, like assured guaranty, who have the skill. They’re interested in the debt that they have insured, and what recovery or reorganizational benefits they would get. This is a controversy. We have never been through this type of restructuring. This is a serious question about Puerto Rico since it is a sovereign, just like the 50 states. It is not permitted to have bankruptcy, yet it has changed the rules by which its internal organization is structured so it may do so. Technically, it’s reorganization, not bankruptcy, as in Chapter 9. ETF.com: What does this mean to the investor? Should an investor in broad munis be concerned here? Are you concerned? There’s a separate set of investors who are in mutual funds. According to Joe Mysak at Bloomberg, his indications were there were 395 mutual funds holding some form of Puerto Rico debt. In holding that form of Puerto Rico debt, they are subjecting their shareholders to risk just like the shareholder would have if the shareholder held the debt directly. I’m really puzzled by the behavior of many retail or unsophisticated investors. There were money flows into mutual funds for holders of Puerto Rico debt—as much as 20 percent in Puerto Rico debt. If you would have polled the same investor and said, “Would you put 20 percent in your muni portfolio in Puerto Rico debt?” they would say, “Absolutely not.” Yet when they bought shares in the mutual fund, that’s exactly what they did. ETF.com: What about for investors with a broad portfolio of municipal bonds that don’t include Puerto Rico? Can this affect the broader muni market as a whole? What the series of events, starting with Vallejo, Calif., and then Jefferson County, and Harrisburg, and Detroit, and now Puerto Rico and others, what this is saying is that the absolute certainty of a pledge on a municipal security is not absolute. It’s possible for folks to go into court, or to use a legislative approach—as in Puerto Rico’s case—and rewrite the rules after the fact. It’s possible for a judge to put a haircut on what was previously presumed to be a 100 percent payment obligation under a municipal bond. In Vallejo’s case, that judge took one series of bonds and reduced the principal obligation to 65 cents on the dollar, and set the stage for others to do it. That’s going to happen to Detroit. There’s going to be a haircut on bonds. It’s going to happen again in other places. It’s clearly going to happen with Puerto Rico debt, because they don’t have the ability to pay. I don’t know where this leads. I mean, there’s an interesting global question for municipal bond investors. The global question is, politicians pass law when it comes to the tough element of paying debt, they revise the law, and how strongly they honor the obligation to pay versus the pressures they have from constituents is a tension. It used to be the bondholder had a higher claim, and it was respected. California law, for example, I think favors bondholders. But there are areas which can come ahead of bondholders. What does a judge do when the judge faces police, fire, the ambulance, closing the schools or deferring the payment to the bondholder? We’re now in a system, and it’s a political system. So I don’t know where this all leads. Yes, I think it’s nationwide in implication. ETF.com: Switching to Treasurys … yields on 10-year notes have fallen from 3 to 2.5 percent in 2014. Where do you see yields at the end of the year? Up until now, the Fed has been at $85 billion a month federally backed security—net new purchases of long duration—and is tapering to zero by October. So the Federal Reserve was able to absorb the entire intermediate- and long-duration issuance of federally backed securities, Treasurys and federally guaranteed net mortgages. If you have a buyer of a central bank that is taking 100 percent of the long-duration inventory being created by the government, how can you possibly expect the interest rates to rise? So here we are, now, in July. The Fed, for the first time in August and September and October, will be absorbing less than the new issuance net of the federal government. When we get to October, the Fed will be at zero. The federal government, though, will still be running at a deficit of maybe $400 billion, $450 billion, on average $35 billion or $40 billion a month. That will be the first time that the Central Bank’s policy impact will be fully neutral. If the Fed replaces long maturity with new long-maturity purchase, what it’s doing is rolling over its neutral position. It will not be reducing the duration of its holdings; they’re already very long. The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has gone from a 2 duration to a 6. It virtually cannot go very much longer. There isn’t any paper left to buy to make it longer. So I expect interest rates in intermediate- and longer-term Treasurys to begin to reflect this change and to do so this year, and then to do so for the next or ensuing one, two, three or four years. Now, the longer the Fed takes to raise the short-term interest rate, the more inflation expectation or fear bias creeps into the long-term interest rate. So the Fed is waiting on the short-term interest rate. At the earliest, it’ll be in the first half of 2015. If you asked where will the short-term interest rate be in the middle of next year, my guess is somewhere between 25 and 50 basis points on the low side, and 100 on the high side. When that happens, and whether that is the first quarter, second quarter, third quarter or fourth quarter, I don’t have a clue. Where would the 10-year Treasury be under those circumstances? It would likely be higher. It would likely probably be closer to above 3 percent than below it, because the Fed will only do that if nominal GDP is above 3 percent, meaning 2 percent real growth, 2 percent inflation or some combination of things like that. ETF.com: What about high-yield debt? Fed Chair Janet Yellen recently raised concerns about the junk bond market. What’s your view on the direction of credit spreads on high-yield debt? There’s a period of time when the Fed policy of zero interest rates acts to suppress volatility. It’s been doing it. Furthermore, it’s been doing it in conjunction with the other central banks of the world, so that worldwide volatility has been suppressed by worldwide zero-interest-rate policy. When you suppress volatility, you narrow credit spreads by definition. Therefore, lots of credit spreads are narrow, not just junk: corporate credit spreads, mortgages. There are a lot of places you can look and say, “These spreads are very tight.” They will be tight until they stop being tight. Now, here is the issue: Can institutions and central banks have some gradual widening of credit spreads? Is there some mechanism by which you can have a longer-term trend change with a benign alteration of these spreads? That’s what the central banks want to try to do. My personal opinion is they will fail. The history of these things is that, when changes finally happen, they’re abrupt, and they are inflection points that are pronounced, not gradual. Currently, in the junk bond credit spread, we’re in that condition. As long as the zero-interest rate suppresses volatility, the bias towards these spreads is to tighten. The minute that changes, I fear for others. And in our case, we’ve decided not to take on that risk. The chasing of yield by sacrificing credit quality is currently a mistake, from an investor’s point of view. And in our shop, we’re not doing it. ETF.com: What is your favorite fixed-income play at the moment? Where can investors park their cash in fixed income? Those securities are tax-free, and they are yielding the same thing as the taxable Treasury. Now one might say, “Why don’t they yield more?” The reason is that there are offshore foreign buyers who buy them every single time the yield gets to be 105 or 110 percent of Treasurys. Because the foreign buyer—we call them crossover buyers—says, “I know I have the U.S. tax code arbitrage on my side. I can get higher yield owning Yale than the Treasury. The creditworthiness is nearly the same.” There’s 100 years of history, and there have been zero defaults out of a true AAA scale. So that security is cheap, unless you think the income tax code of the United States is going to be repealed, and I don’t see that happening very soon. ETF.com: On the equity front, last quarter you said you were bullish on energy and utilities. Have there been any changes on that front in the past three months? We are still long the utility position through XLU. We are overweight, and I actually, on the pullback, have done a little rebalance and bought a little more today [7/16/14]. My heaviest overweight is utilities. I am now underweight small-caps. We’ve exited the small-cap positions. I’m worried about the market. So I have a cash reserve, which is growing. The S&P at 1970 or 1980 is making me nervous. For the first time, I can see this shift in Fed policy, so that the excess liquidity support of the stock market is disappearing. To me, the inflection of that is, right now, this summer—July, August, September, October. Up until now, when they were at $85 billion going to $75 billion, I had the opinion that tapering was not tightening. Now I think, in this period right now—July and August—tapering has now reached the point where federal finance is on its own. To me, it’s a crossover to the first element of tightening. It’s been years since we had it. I don’t think the market is prepared for it, so I want cash. ETF.com: Thanks for your time. ~~~~ David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment