The Big Picture |

- How Do Liquidity Conditions Affect U.S. Bank Lending?

- Succinct Summation of Week’s Events 10.17.14

- End of OPEC = Golden Swan

- I Dare You to Try to Refinance. Go Ahead, Just Try.

- 10 Friday Reads

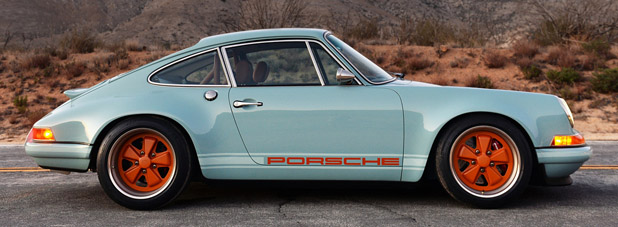

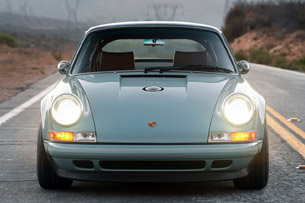

- 1991 Porsche 911, Reimagined by Singer

| How Do Liquidity Conditions Affect U.S. Bank Lending? Posted: 18 Oct 2014 02:00 AM PDT How Do Liquidity Conditions Affect U.S. Bank Lending?

Possible Bank Responses to Liquidity Risks There also might be different responses to liquidity risk by U.S. banks that are domestically oriented compared with banks that are more global. Because these two types of banks have very different business models, the channels and magnitude of transmission of liquidity risks into bank lending may differ significantly. Small domestic banks have relatively strong lending responses to liquidity risks (Kashyap and Stein [2000]; Cornett, McNutt, Strahan, and Tehranian [2011]). By contrast, banks with foreign affiliates, particularly large banks, actively move funds across their organizations to offset such risks, and potentially insulate lending in their home markets (Cetorelli and Goldberg 2012). However, these same banks may decrease lending abroad as they move liquidity into their home country. For both types of banks, changes in aggregate private liquidity are likely to influence lending differently in crisis than in normal periods, in part because of the availability of and willingness to use official sector liquidity facilities in periods of aggregate liquidity stress. When banks have access to central bank liquidity facilities priced at terms below private market rates, this might relax the constraints imposed by the composition of banks' balance sheets on their access to external funding, leading to a different relationship between those balance sheet characteristics and the banks' lending (Buch and Goldberg 2014). The Framework for Studying How Liquidity Risks Affect Bank Lending The second building block is Buch and Goldberg (2014), who integrate into this framework considerations specific to global banks, and also show the potential consequences of bank access to official sector liquidity facilities. For the global banks, strategies for liquidity management can play an important role and these strategies are reflected by the use of internal funding transactions between the head office and its domestic and foreign affiliates. The balance sheet characteristic that reflects this feature of global banks is their reported use of "net due to" or "net due from" their affiliated institutions, which refers to their borrowing from or lending to other parts of the bank holding company. We focus on a sample of U.S. banks, using data from 2006 through 2012. We concentrate only on larger U.S. banks (with more than $10 billion in assets) and we distinguish between banks with claims booked through foreign affiliates (global banks) and those without such claims (domestic banks). These two groups of banks can lend to both domestic and foreign borrowers. In the case of global banks, lending to foreign residents can be arranged either through cross-border transactions or through their foreign affiliates (which take the form of a subsidiary or branch). Our measures of aggregate liquidity strains in financial markets are the rates that banks use when lending to one another, known as interbank spreads (such as the London interbank offered rate over the overnight indexed swap, known as the Libor-OIS spread). As shown in the chart below, these rates spiked during the financial crisis as U.S. and European banks became less willing to lend to one another and liquidity dried up, especially at maturities beyond a few days. Our tests take into account banks' use of official sources of liquidity. In 2008, the Federal Reserve announced a number of extraordinary official liquidity facilities to relieve the strains in U.S. financial markets during the crisis. Because the cost of funds at official facilities was at times lower than private market rates, we allow for a different response of individual banks to aggregate prices of liquidity during periods when the bank taps official sector facilities. Thus, our analysis incorporates information by bank on when institutions accessed the Term Auction Facility (TAF) and discount window, and incorporates the balance sheet characteristics of these same financial institutions as well as their global nature to understand differences in the transmission of liquidity risk to loan and credit growth. What Matters for the Effects of Liquidity Risk By contrast, we find that for global banks, the impact of liquidity shocks depends more on their liquidity management strategies, as reflected in outstanding internal borrowing or lending between the head office and the rest of the organization. Net internal borrowing (liabilities from the head office to its affiliates minus claims by the head office on those affiliates) increases in periods with heightened liquidity risk for the U.S. banks that have higher outstanding unused commitments and lower Tier 1 capital ratios. This higher net internal borrowing is associated with relatively more growth in domestic lending, foreign lending, credit, and cross-border lending. The economic magnitude of the effect of net internal borrowing on domestic C&I loans is also large: a bank that finances 6.6 percent of the head office liabilities (in the 75th percentile) with internal net borrowings would lend $800 million (or 5 percent of domestic C&I lending of the median bank) more in a given quarter than a bank that only finances 1.2 percent of its liabilities (in the 25th percentile) with these funds, after a 100-basis-point increase in the Libor-OIS spread. We find that cross-border lending and internal borrowing and lending tend to be more volatile than domestic lending and lending conducted through U.S. bank affiliate offices abroad. The model we estimate explains some of the observed changes in domestic loan growth, as well as changes in internal capital market positions, but doesn't capture as much of the volatility in cross-border lending growth of U.S. banks. At the same time, cross-border lending appears to be sensitive to more bank balance sheet characteristics than any of the other forms of lending. Regardless of the form of lending, the role of bank balance sheets is diminished when liquidity risks increase substantially and the banks access official sector liquidity. Thus, official sector liquidity moderates the effects of private sector liquidity risk on both domestic lending and cross-border flows. Disclaimer Ricardo Correa is a section chief in the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System's International Finance Division.

Tara Rice is a section chief in the Board of Governors' International Finance Division. |

| Succinct Summation of Week’s Events 10.17.14 Posted: 17 Oct 2014 01:00 PM PDT Succinct Summations of Week ending October 17th Positives:

Negatives:

Thanks, Batman! |

| Posted: 17 Oct 2014 10:30 AM PDT Could the Dissolution of OPEC Become a Golden Swan?

We all know that I’m bearish. To me (at the current time), this is a stock market with no memory, no momentum and no motivation. It is a foundering market that appears to be waiting for trouble to arrive on a Black Swan landing strip. But, as always, it’s important to recognize that I don’t have a concession on the truth. I can be — and have been — (very) wrong in the past! This morning and in the day’s ahead I will discuss some potential Golden Swans that could be viewed as an important and incremental positive for the markets and for the global economies. The first Golden Swan that I will discuss this morning is the possible dissolution of OPEC. OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) is an intergovernmental organization that was created at the Baghdad Conference in September 1960 by Iraq, Kuwait, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. Later Libya, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Indonesia, Algeria, Nigeria, Ecuador, Angola and Gabon joined. OPEC’s mission was to coordinate the policies of the oil producing countries. Its goal is to secure a steady stream of oil income to the member states and to collude in influencing the world oil prices through economic means. Because OPEC is an organization of countries (not oil companies), individual members have sovereign immunity for their actions, meaning that OPEC is not regarded as being subject to competition law in the normal way. While OPEC was established in 1960 it did not become an impactful force in the market until 1973 when its policies caused a four-fold increase in the price of oil (from about $2.63 a barrel to $11 a barrel, helping to cause a serious global recession and a devastating bear market in stocks. OPEC operated as a classic cartel, utilizing artificial means to raise the price of its product. While economic theory teaches that cartels are transitory, OPEC has had staying power. Virtually every investment professional managing money today has done so under the influence of OPEC on the oil market. Indeed, it is hard, if not impossible, to imagine a world without OPEC. But just as we are constantly trying to find Black Swans before they appear, if OPEC ceases to function or its influence wanes, it could be a possible “Golden Swan” that no one sees coming. The ramifications of this would be profoundly positive for global economies and markets. Powerful forces are now forming to suggest OPEC’s days are numbered and that, at the very least, its impact will wane. The Growing Influence of the U.S. on Energy Production — The U.S., through hydraulic fracking, has become a major oil producer and our imports have fallen, helped by secular efficiency in consuming energy. For one reason or another (some discussed above), members are unlikely to cooperate in withholding production to maintain price. Over the next 1-2 years the price of oil may move below the marginal cost of production. This could translate into sharply lower energy prices and consequently higher consumer real incomes (and spending) than anyone is forecasting. IF this happens, the overall market should be ignited to the upside, with particular strength in the consumer and transportation sectors and with weakness seen in energy production and exploration issues. The relatively positive action of the retailers over the last week or two might be an early signpost that the role of OPEC is diminishing and that the price of energy products might continue to decline. The bottom line is that a lengthy period (54 years) of the pain of inflated energy prices may now be coming to an end in what might be called a Golden Swan of Lower Oil Prices. To say the least, the OPEC meeting late this month should be interesting. Position: None Douglas A. Kass 411 Seabreeze Avenue Web Site: http://www.seabreezepartners.net The information contained in this e-mail and any enclosures or attachments may be privileged and confidential and protected from disclosure. If the reader of this message is not the intended recipient, or an employee or agent responsible for delivering this message to the intended recipient, you are hereby notified that any dissemination, distribution or copying of this communication is strictly prohibited. If you have received this communication in error, please notify us immediately by replying to the message and deleting it from your computer. The sender disclaims all responsibility from, and accepts no liability whatsoever for, the consequences of any unauthorized person acting or refraining from acting on any information contained in this e-mail and any enclosures or attachments. This e-mail shall not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy, which may only be made at the time a qualified offeree receives a confidential offering memorandum describing the offering and a related subscription agreement. No offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to buy shall be made in any jurisdiction in which such offer, solicitation or sale would be unlawful until the requirements of the laws of such jurisdiction have been satisfied. |

| I Dare You to Try to Refinance. Go Ahead, Just Try. Posted: 17 Oct 2014 07:00 AM PDT The bond market seems to have had its own flash crash this week. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond dipped briefly below 2 percent, as panicked equity sellers looked for a safe place to park their cash. Treasuries, of course, are the world's option of choice, the safest and most liquid port during the storm. Demand for bonds has helped drive down mortgage rates as well. Bloomberg News reported that "U.S. mortgage rates plunged, sending borrowing costs for 30-year loans below 4 percent for the first time in 16 months, as signs of a slowing global economy drove investors to the safety of government bonds." Almost immediately, lower rates worked their way through the entire credit complex. The average rate on 30-year fixed home loan is now 3.97 percent. To put this into context, the median U.S. home price is $219,800. Put down 10 percent and that $200,000 mortgage costs the homebuyer $951 a month. A decade ago the same mortgage would have cost this buyer as much as 6.34 percent. The monthly payment would have been more than 25 percent higher at $1,243. The chart below shows the long decline in rates:

Under normal circumstances, this decrease in rates should have far reaching and beneficial effects on the economy. It would spur increased investment in real estate. Mortgage refinancings also would rise, and that would put a little more discretionary cash in the hands of consumers each month. |

| Posted: 17 Oct 2014 05:00 AM PDT I have been traveling the past few days — did I miss anything? Once again, morning train reads:

|

| 1991 Porsche 911, Reimagined by Singer Posted: 17 Oct 2014 03:00 AM PDT Jay Leno’s Garage: 1991 Porsche 911, Reimagined by Singer. Feast your eyes on Singer Vehicle Design’s meticulously restored and optimized air-cooled Porsche icon.

From WSJ:

More photos after the jump . . .

|

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment