The Big Picture |

- Jay Leno’s Garage: 2014 Corvette Stingray

- How Liquid Is the Inflation Swap Market?

- Books Bought By Big Picture Readers (March 2013)

- 10 Wednesday PM Reads

- Why Is Wall Street So Hot for Solar Energy?

- 1901: When US Currency Was Beautiful

- AAII: Cash Allocations at a 16-Month High

- 10 Wednesday AM Reads

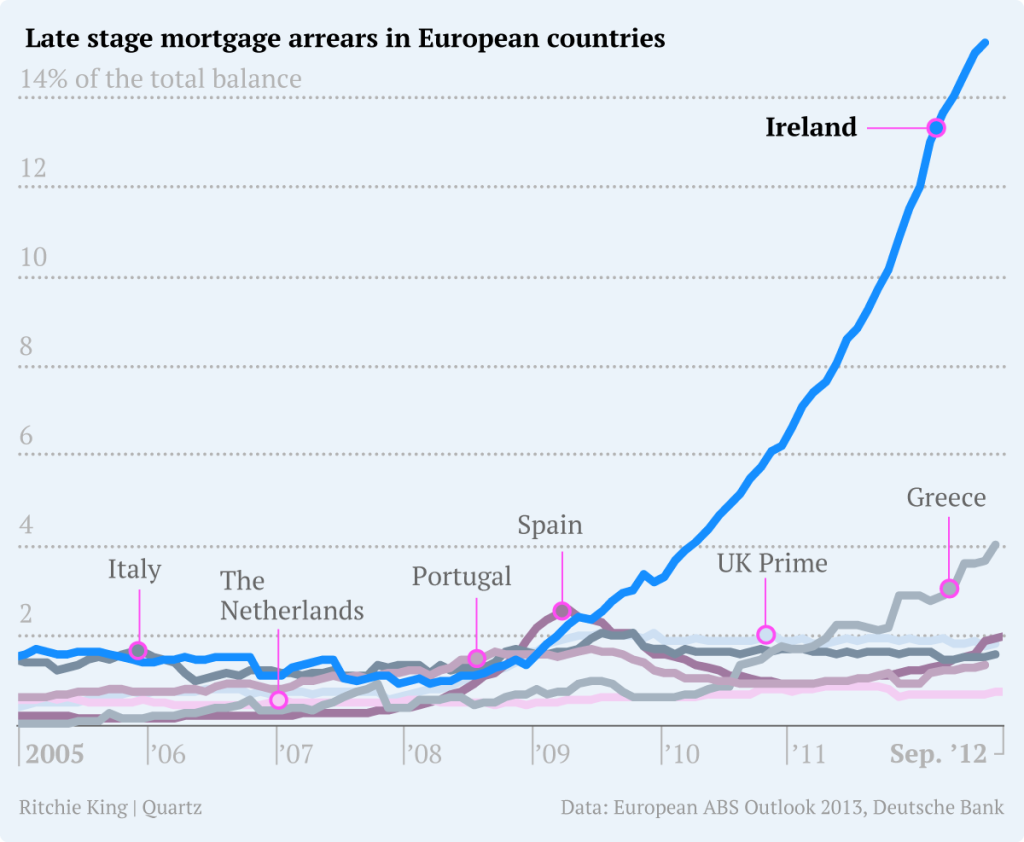

- The Most Insane Chart Ever: Irish Mortgage Arrears

- Contagion Starts Small

- Why Your Best Ideas Come in the Shower

| Jay Leno’s Garage: 2014 Corvette Stingray Posted: 04 Apr 2013 02:00 AM PDT 2014 Corvette Stingray – Jay Leno’s Garage |

| How Liquid Is the Inflation Swap Market? Posted: 04 Apr 2013 01:00 AM PDT How Liquid Is the Inflation Swap Market?

Inflation swaps are used to transfer inflation risk and make inferences about the future course of inflation. Despite the importance of this market to inflation hedgers, inflation speculators, and policymakers, there is little evidence on its liquidity. Based on an analysis of new and detailed data in this post we show that the market appears reasonably liquid and transparent despite low trading activity, likely reflecting the high liquidity of related markets for inflation risk. In a previous post, we examined similar issues for the broader interest rate derivatives market. Inflation Swaps Defined The figure below illustrates the cash flows for a zero-coupon inflation swap—the most common inflation swap in the U.S. market. As the name "zero-coupon" swap implies, cash flows are exchanged at maturity of the contract only. The fixed rate (the swap rate) is negotiated in the market so that the initial value of a trade is zero. As a result, no cash flows are exchanged at the inception of a swap. Market Is Modest in Size, but Growing Quickly Transaction Data Point to Low Trade Frequency Trading Concentrates in Certain Tenors Trade Sizes Are Large and Fairly Standardized

Prices Seem to Be Transparent Why Is the Market So Liquid Despite the Low Trading Frequency? Disclaimer

|

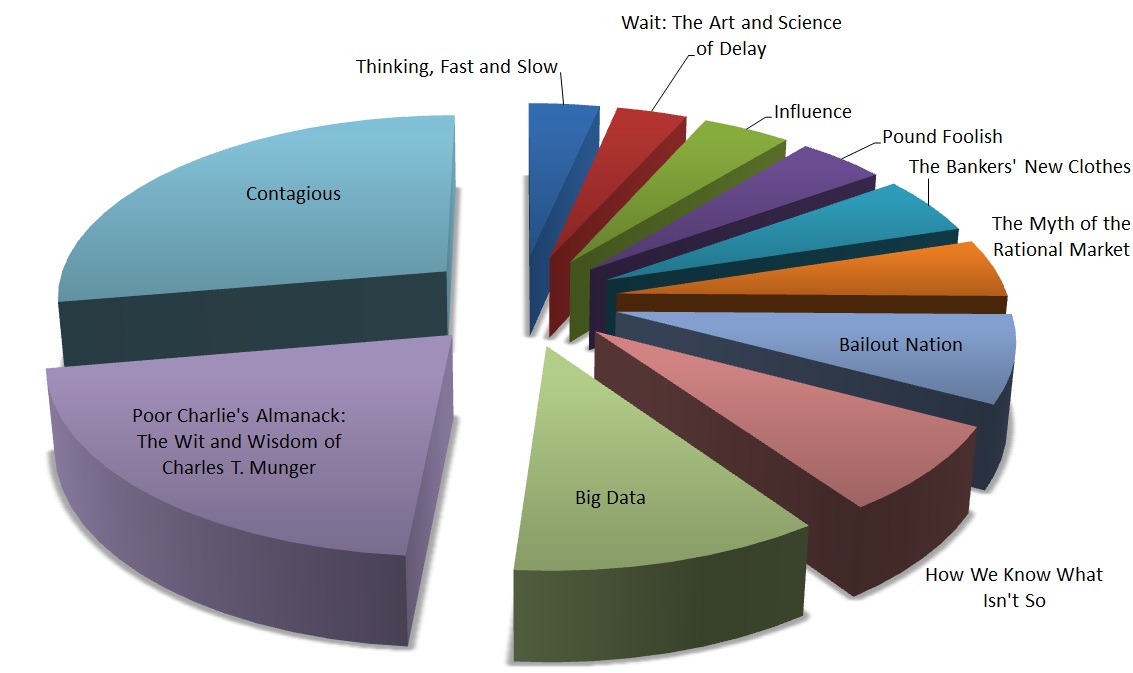

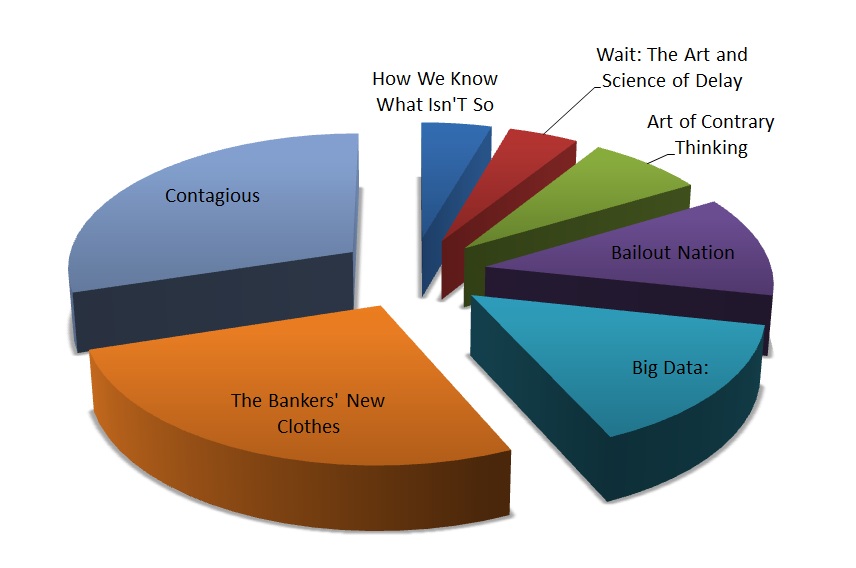

| Books Bought By Big Picture Readers (March 2013) Posted: 03 Apr 2013 04:00 PM PDT

Once again, its time to peruse the data to see which books TBP readers bought last month via Amazon's magic embed code (we can track click from these links). Its anonymous — I don't know who bought what — but there's lots of data on the various books generated. These were the most popular TBP books for March:

Kindle and eBooks after the jump

Click to enlarge: These were the most popular TBP Kindle eBooks for March:

|

| Posted: 03 Apr 2013 01:30 PM PDT My afternoon train reading:

What are you reading?

Chart of the Day |

| Why Is Wall Street So Hot for Solar Energy? Posted: 03 Apr 2013 01:00 PM PDT What should investors know about the solar industry? OneRoof Energy CEO David Field explains on Markets Hub. Source: MarketBeat |

| 1901: When US Currency Was Beautiful Posted: 03 Apr 2013 11:30 AM PDT United States $10 Banknote, Legal Tender, Series of 1901

Back in the day, US currency did not have Presidents on it, but rather, consisted of “animals and symbolic statuary” as well as landscapes. |

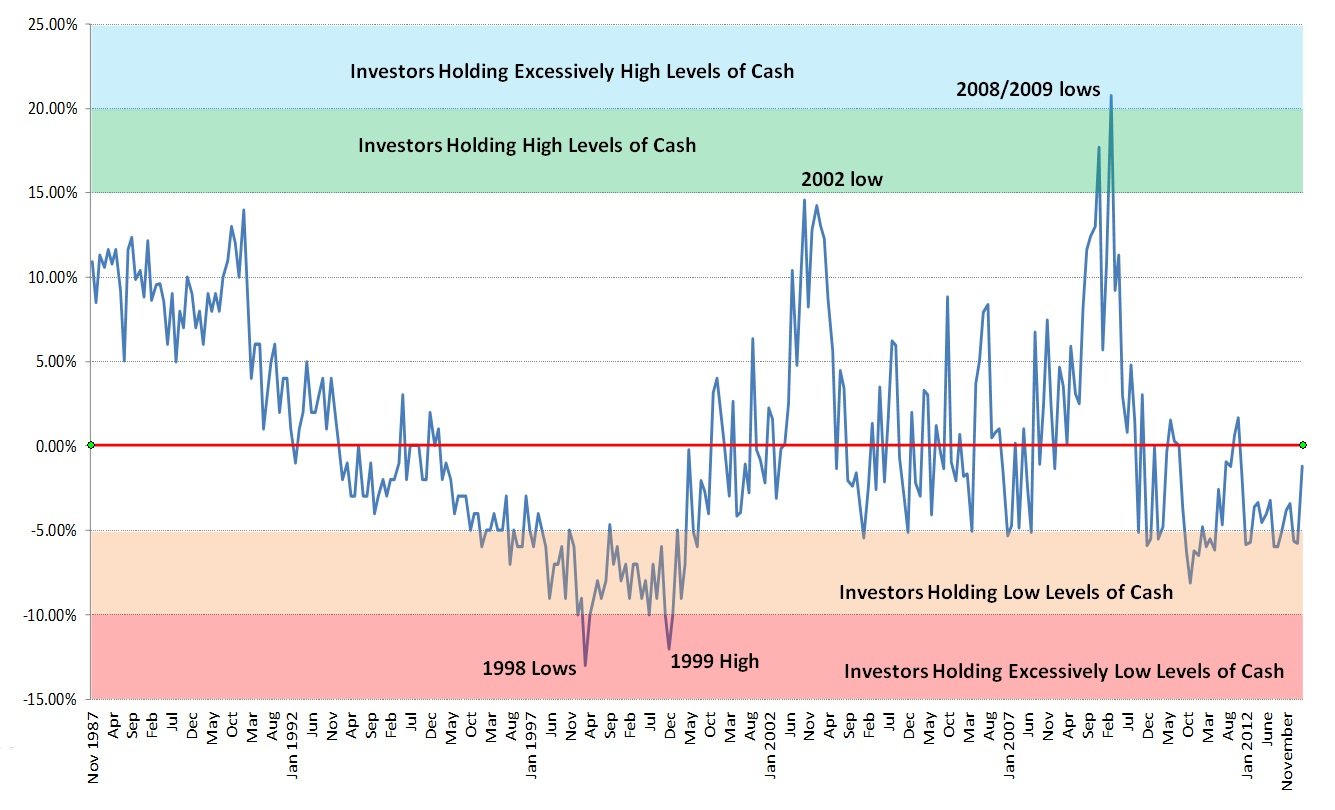

| AAII: Cash Allocations at a 16-Month High Posted: 03 Apr 2013 09:10 AM PDT click for ginormous chart

Today, lets look at another interesting data point from AAII: Cash allocations reached a 16-month high in March. Individual investors pulled money from both equities and bonds last month. We have shown the flip side of this chart in the past — equity allocation — which is similarly moderate. Equity allocations fell 3.0 percentage points to 59.5% in March. Surprisingly, the past 15 months have not seen much variation in equity allocations stuck in a range from 58.8% (June 2012) to 62.5% (February 2013). The historical average is 60%. March AAII Asset Allocation Survey results:

Historical Averages:

|

| Posted: 03 Apr 2013 06:45 AM PDT My morning reads:

What are you reading?

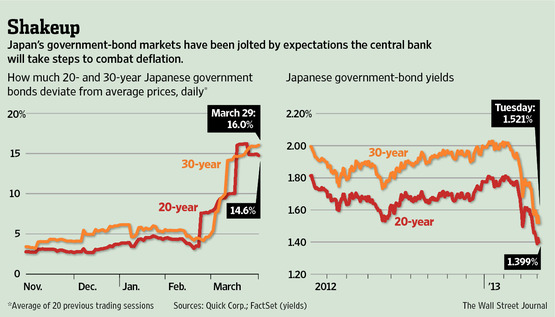

Rare Jitters for Japan’s Bonds |

| The Most Insane Chart Ever: Irish Mortgage Arrears Posted: 03 Apr 2013 04:00 AM PDT Ireland's Homeowners: Global Champions in not Repaying Mortgages Source: Quartz via Deutsche Bank, Moody's

Cyprus? Pshaw. Greece, Italy, Spain Portugal? Puh-leeze. Ireland sets the bar for what mortgage arrears looks like ina country bankrupted by their financial sector and hoodwinked by a bank bailout. The chart above, showing mortgage arrears on the emerald isle, may be the single most insane chart I have ever seen. And the details underlying it are just as insane. Via Matt Phillips at Quartz:

Oh, and the country’s National debt is up 4X as Unemployment rate has risen above 14%. The full article at Quartz is well worth your time.

Source: |

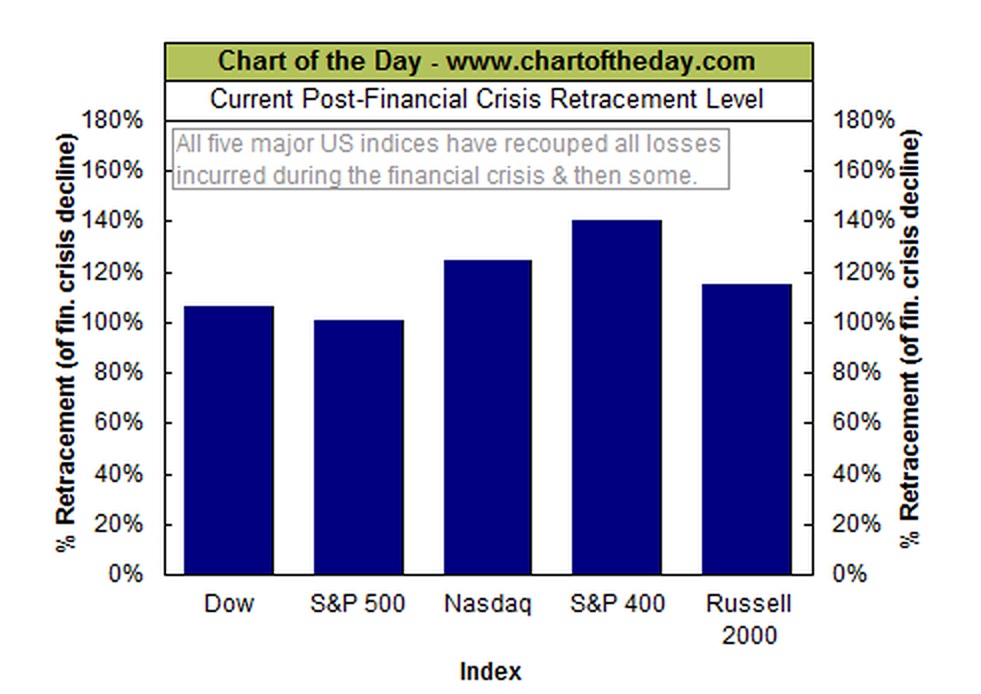

| Posted: 03 Apr 2013 03:00 AM PDT Contagion Starts Small

First we must correct an error. In our discussion “Euro: Requiem or Renewal?” we identified Jeroen Dijsselbloem as a central banker. That was an error; he is a political figure. There is quite a distinction between experienced central bankers and finance ministers who developed their careers as politicians. Dijsselbloem is definitely the latter. Now to our commentary: Contagion Starts Small History indicates that contagions start small. What is worrisome about Cyprus is the complacency that markets are showing, based on the assumption that it is a little, one-off, insignificant event. Here is a little refresher on contagion, and then we will go back to Cyprus. 1. Russian ruble collapse. Remember 1997 and 1998. The sequential problems in worldwide currency-trading exchanges ended with the collapse of the Russian ruble and the demise of the Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) hedge fund. It did not start with the LTCM collapse; that was the final market shock, which triggered a large government intervention. That brought in Alan Greenspan and the US Federal Reserve. The collapse actually started with a single-currency failure in Thailand. Panicked trading in the Thai baht started as what looked like a small, one-off, insignificant event. The contagion from that event took about 18 months to play out. 2. Zimbabwe inflation. The earliest signs of inflation, confiscation of wealth and appropriation of property, and oppression of the populace in Zimbabwe appeared many years before hyperinflation, full destruction of the currency, and suppression of the productive facilities of the country. The collapse was in the incipient stage long before it became evident that the government's policies were going to accelerate, rather than prevent it. I saw this one coming firsthand. As chair of the Global Interdependence Center's central banking series, I recall meeting with representatives of Zimbabwe and its central bank. We discussed the risks they were taking in the early stages of aggressive monetary expansion as an attempted solution to their problems. We warned them about appropriation of wealth. They were emphatic that they were controlling capital and monitoring the inflationary effects of what was then a very early-stage policy. Those of us who sat in that meeting listened to the representatives for an hour and a half and then spent the next hour and a half attempting to persuade them that their policy would lead to the demise of wealth and investment in their country. A few years later, the outcome became apparent to the world. 3. Weimar Republic hyperinflation. When the Weimar Republic attempted to meet international flow requirements under the Treaty of Versailles, it did not immediately cause hyperinflation. The process started with currency expansion and banking manipulation in an attempt to manage foreign-exchange flows. It ended with hyperinflation, the demise of the government, and the rise of Nazism in Europe. Thus, the European contagion did not begin with the fall of the government and rise of Hitler in the 1930s; it started years earlier. In a marvelous piece of research, economist Madeline Schnapp documented this history in monetary terms. When Germany went to war in 1914, an egg cost 2 pfennigs and a loaf of bread was 10 pfennigs. In 1919, after the war ended and at the birth of Weimar, the egg was 20 pfennigs and the loaf was 1 mark. By April 1922, the egg was 4 marks, by September 9 marks, and by November 22 marks. In February 1923, the egg cost 45 marks, by May it was 800 marks, in July 1923 it cost 20,000 marks, and by August it was ten times that much: 200,000 marks. At the end of 1923 one needed billions of marks to purchase an egg, and a 1 trillion marks to buy a loaf of bread. 4. The US financial crisis of 2007-09. Thinking back on the recent crisis in the US, we saw the first signs of weakness in the financial sector in mid-2007. There were some pricing anomalies in May that were visible but not explained. Clearly some money movement was taking place, but it was not apparent why. By summer 2007 Bear Stearns had indicated a problem with some mortgage-backed securities. They said it was just a couple billion – not very significant. In 2007, the first signs of the contagion were minor. Now let us put this perspective to work with regard to Cyprus. We now know that some bank accounts in Cyprus will lose up to 60 percent of their balances. Think about that as if you were a business operating in Cyprus with an active €1 million balance. You need the funds to handle payrolls and trade relationships and to pursue the ongoing operational activities of your enterprise. Suddenly, €600,000 of your €1 million is impounded. About two-thirds of it is exchanged for shares in a new banking facility. Those shares may be worthless, and at best you will not know for a long time how much, if any, value can be obtained from them. The other one-third of your impounded balance is held in reserve and kept from you. Your access to the remaining 40% of your account is limited to small transfers and withdrawals. Can the multiplier effects of that business's problem be contained within Cyprus? Perhaps, if that business is a local retail enterprise. It may fail, and many others like it may fail, and the country may suffer an economic decline of large proportions. But can the effects really be limited to Cyprus? Retail enterprises in that small island nation must purchase many imported goods, and they must somehow fund their business activities Those transactions, when they are restrained or defeated by a punitive Eurogroup policy directed at Cypriot banks, trigger negative multiplier effects that may blossom into serious Eurozone-wide contagion. We do not yet know the impact of Cyprus. We will not have a sense of its full depth for months. Contagions in economic systems are dangerous, as our list above demonstrates. European reaction to Cyprus is still developing. Markets are already reallocating funds away from places like Malta and Slovenia. Markets are worried about larger countries that are also troubled, like Spain and Italy. The most recent unemployment report from the eurozone validates our view. It is 12%, up from 10% just two years ago. Markets are also looking at New Zealand, which is proposing a bank reconciliation mechanism similar to the one applied by the Eurozone in Cyprus. It is called Open Bank Resolution (OBR). Google it and read about the debate in New Zealand. We suspect that monies that are able to leave New Zealand are already doing so. If I had money in a New Zealand bank and if I had seen a proposal indicating that a governmental authority or the central bank might confiscate some portion of my account if they had to resolve one of New Zealand's banks, I would be thinking about moving it right now . This whole notion of breeching the wall of the deposit is now pervasive worldwide. A joint US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) – Bank of England paper (December 10, 2012) was titled “Resolving Globally Active, Systemically Important, Financial Institutions.” Note paragraph 47 and its discussion of small deposits and insured deposits. Here is the link: http://www.fdic.gov/about/srac/2012/gsifi.pdf . Query: How do you decide how large a deposit balance is needed to conduct business operations? Where is the line drawn if that balance is above the deposit-insurance limit? In the US, unlimited FDIC coverage of non-interest-bearing demand deposits has expired. Now what? How does one protect oneself? In New Zealand one needs to avoid exposure to banks, if possible. In the Eurozone, we know that the intent is to preserve the insurance limit in each of the 17 countries. We also know that the finance ministers in the Eurogroup attacked small depositors and would have succeeded were it not for the Cypriot parliament. In the US, we know that the FDIC has honored its commitment to deposit insurance. The same is true in the UK. We also know that in both countries there is new law (not tested yet) that suggests that a bank that has exhausted all resources and does not have the assets to either merge or be resolved fully without invading insured deposits, now presents an additional risk to the insured depositors. We do not expect that the insured depositors would lose their funds, but we do note that their safety is not as clear-cut as it once was. In the US we are seeing small and independent businesses revamping their deposit allocation structures to stay within the $250,000 limit of the FDIC. We do not blame them. In our own firm we have a similar policy. We just do not blindly trust any banking system. It is safer to view them as riskier than they used to be. So what does all this mean for investors? Contagions start small. They expand, or not, depending on subsequent events. Actions of governments can mitigate damage or enlarge it. A second bank failure that is resolved with large depositor losses in Europe will have a much greater systemic impact than the first one in Cyprus. The increasing use of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) in any Eurozone country will be seen as a warning sign that the Cyprus events may be repeated. Attempts to veil ELA data will exacerbate the problem. Transparency reduces damage. It is hard for governments to grasp that concept, so it is not likely to prevail. Investors have choices. They can seek higher returns and will often take risks to get them. Or they can follow the advice often attributed, though perhaps erroneously, to a great economist by the name of Will Rogers: "I am not so much concerned with the return on my money as I am with the return of my money." We are in a day and age in which the short-term interest rate in every major currency of the world is near zero. Compensation for risking wealth in a deposit structure is small. Safety is obtainable at low opportunity cost. Investors are wise to seek it. At Cumberland, we are placing increasing emphasis on the highest quality of credit. When interest rates are very low, investors are not properly compensated for credit risk. They tend to go in the opposite direction at such times, chasing yield and buying lower-investment-grade or junk credit in order to attempt to maintain income. Some people pursued that strategy in Cyprus by getting relatively high deposit interest rates through banks. The banks were able to pay those interest rates because of their holdings in junk-status sovereign debt, such as Greek government bonds. Now, the contagion flows have offset the extra interest earnings many times over. An investor who chased yield in a Cypriot bank in order to capture a few hundred additional basis points in interest is now paying a very serious price for that strategy. Contagion starts small, and we may now be witnessing one gathering momentum in the Eurozone. We had a similar experience in 2007-2008 and through to early 2009 in the US. We have subsequently developed a legal-resolution structure under Dodd-Frank that has altered the method of intervention in the US, and there have been similar changes in the UK and elsewhere. The danger for those who are willing to chase yield and take on more credit risk is rising. At Cumberland, our strategy is to avoid all imbalances of risk vs. return. We are diligently emphasizing higher-quality credit. ~~~ David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer, Cumberland Advisors |

| Why Your Best Ideas Come in the Shower Posted: 03 Apr 2013 02:00 AM PDT WSJ’s Sue Shellenbarger and Grey New York president and chief creative officer Tor Myhren look at what context, time-of-day and mood have to do with generating bright ideas. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment