The Big Picture |

- Whipsaw

- The Bank War

- Invest As If The Sun Is Coming Up Tomorrow

- 10 Sunday Reads

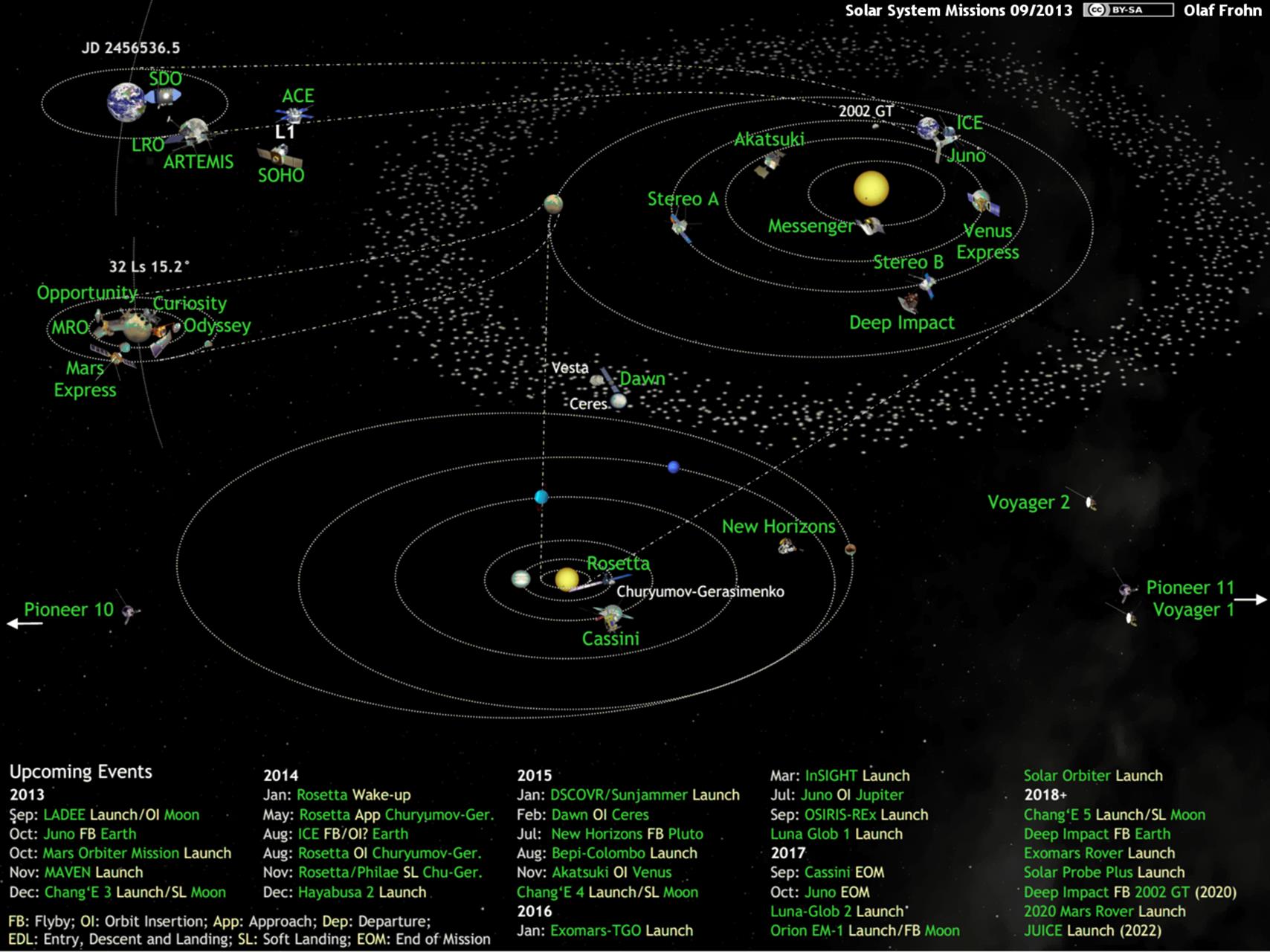

- Solar System Missions

- The Economics of Student Loan Borrowing and Repayment

| Posted: 14 Oct 2013 02:00 AM PDT Whipsaw

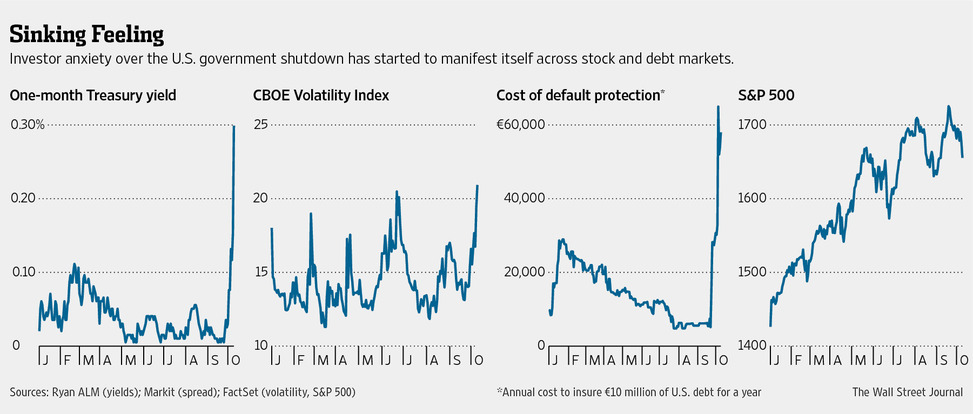

A whipsaw is a “long, narrowing, tapering ripsaw, usually set in a frame and worked by one or two persons.” Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, second edition. What a play on words. “Long,” as in, we are now passing two weeks of shutdown. Different scenarios take this Washington theatre out to Thanksgiving, Christmas, or into January. A few weeks’ delay may not resolve anything. “Narrowing,” as in the cash balance at the US Treasury. Will the Treasury run out of cash on October 17? We think not. Will the crunch hit in November, starting with the Social Security payments on November 1? And be exacerbated by the November debt payments? We think that might be a more likely pressure point. Will the Republicans point to the Treasury on October 18 and say, “See, the world did not end yesterday; you misled us”? Get ready for that political round. “Tapering,” as in the on-again, off-again Fed policy of reducing the amount of new purchases of securities. Current Fed policy is to buy $85 billion a month. What does the Fed do when the debt-limit debate stops the creation of new securities? Is any potential policy change being injected into the debate? The actual federal deficit is now under $700 billion and falling. The amount of newly created, federally backed mortgage paper is limited. The Fed is already buying more than 100% of what is newly created. And we may see no debt limit increase by Congress and therefore a forced balanced budget. That would mean no additional net new Treasury debt. The political scene is a whipsaw of news flows and surprises. As a money manager, we know that this is a dangerous way to make investment decisions. We have seen two major whipsaws. Let’s talk about each of them. The first resulted from the rhetorical buildup implying that tapering was coming. This started in mid-May, 2013, and we saw a continuous flow of Federal Reserve officials offering discussions of tapering and accompanying policy. Then came the September FOMC meeting, where the Fed announced there would be no tapering, even though the markets had been primed to expect – and had priced in – the onset of mild tapering. That development triggered a stock market explosion followed by a reality check and sell-off. So whipsaw number one we can blame on the Fed. They created an expectation; they seemed to affirm and reaffirm it; and then they surprised to the contrary. Now they face an October meeting, and markets do not know what to expect. It seems markets are discounting an extension of present Fed policy for several more months, until there is clarity on the budget and debt-limit fights. But if Fed policy is now without much efficacy, does delaying tapering actually help matters? Markets are involved in this debate. So are Fed members. The second whipsaw is underway. It was not long after the tapering whipsaw had reverberated through the markets that the continuing-resolution, budget, debt-limit fight flared up on schedule and escalated to the present impasse. All hope of compromise was smashed, and a resolution has yet to materialize. The intensity of the fight led to the market's perception of a possible risk of US default. We never thought the odds of default were very high, but the intensity of the rhetoric was sufficient to raise them above zero. Markets reacted. US credit default swap pricing spiked. In response, very short-term Treasury obligations became elevated in yield, and the very short end of the Treasury yield curve actually inverted. Announcements came: some large institutions were divesting themselves of short-term Treasurys. The self-perpetuating momentum of fear and panic drove the VIX above 20. A rising VIX and a rising CDS on the United States have always coincided with stock market weakness. Now we have another news flow shift as the whipsaw heads back in the opposite direction. Just because politicians are talking with each other, for two days stock markets have again exploded. I guess the market is celebrating its relief that politicians are talking at each other rather than past each other. How much of the rally was short covering and how much was based on belief that policy will change is impossible to determine. So if the basis for the rally was the expectation that there is a durable political deal actually in the offing, the market's celebratory response seems premature to us. Hence we can expect more whipsaw. Stock prices are based upon many things. The dominant strategic factors are earnings and the prospect for growth of earnings. Earnings come out of profits. The GDP profit share in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) is consistently measured and exhibited in data. These days we cannot obtain current data because of the government shutdown, but we do have ways to estimate what the data would reveal. Without corroborating official statistics the estimates are guesstimates, but the profit share that we can estimate is currently at a very high level. Can it go higher? Yes. Will it? That is much harder to discern. Meanwhile the US economy is operating at a tepid growth rate. Estimates of that growth rate are falling as uncertainty wrought by irresponsible political brinksmanship only acts to slow growth to a lower level than it would otherwise be. All this whipsaw uncertainty created by the government (Congress and the White House) and by the Fed does not help growth accelerate; it causes it to decelerate. Slow economic growth means low earnings growth. The profit share is at a peak level, so risk is rising. Therefore, plunging back into the stock market without dissecting the sectors and being able to clearly see earnings prospects is a dangerous game. Investment actions driven by political whipsaws are not valid, data-driven decisions; they are gambler’s' actions. We have not chased the rally; we are still maintaining cash reserves. Of course, we would like to see the US government operate in accordance with the principles of good governance. Of course, we would like to see the political leaders of our country reach longer-term, sustainable, and dependable agreements on the budget and debt, and proceed to implement them. But the truth is, we distrust politicians, and what we are watching is failed governance. This is true for the White House, the Senate, and the House of Representatives, and for Democrats as well as Republicans. We have to watch their actions and not their words. And we need to hold some cash reserves. Whipsawing will be with us for a while. Stock market entry points for a fully invested position are best found either when cheap pricing and high negative sentiment combine or when there is clarity of policy. Right now, neither of these exists. ~~~ David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer, Cumberland Advisors

|

| Posted: 13 Oct 2013 04:30 PM PDT

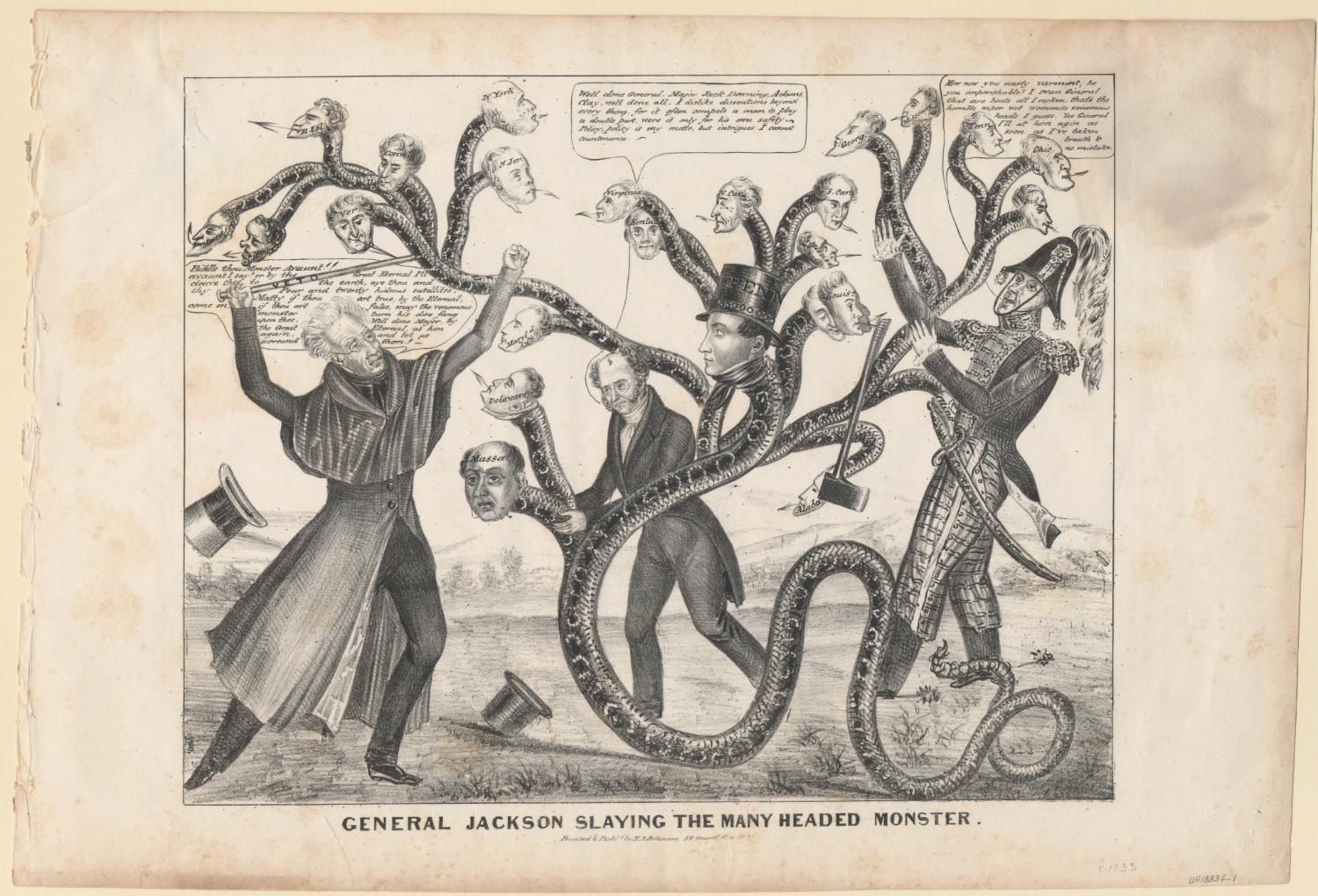

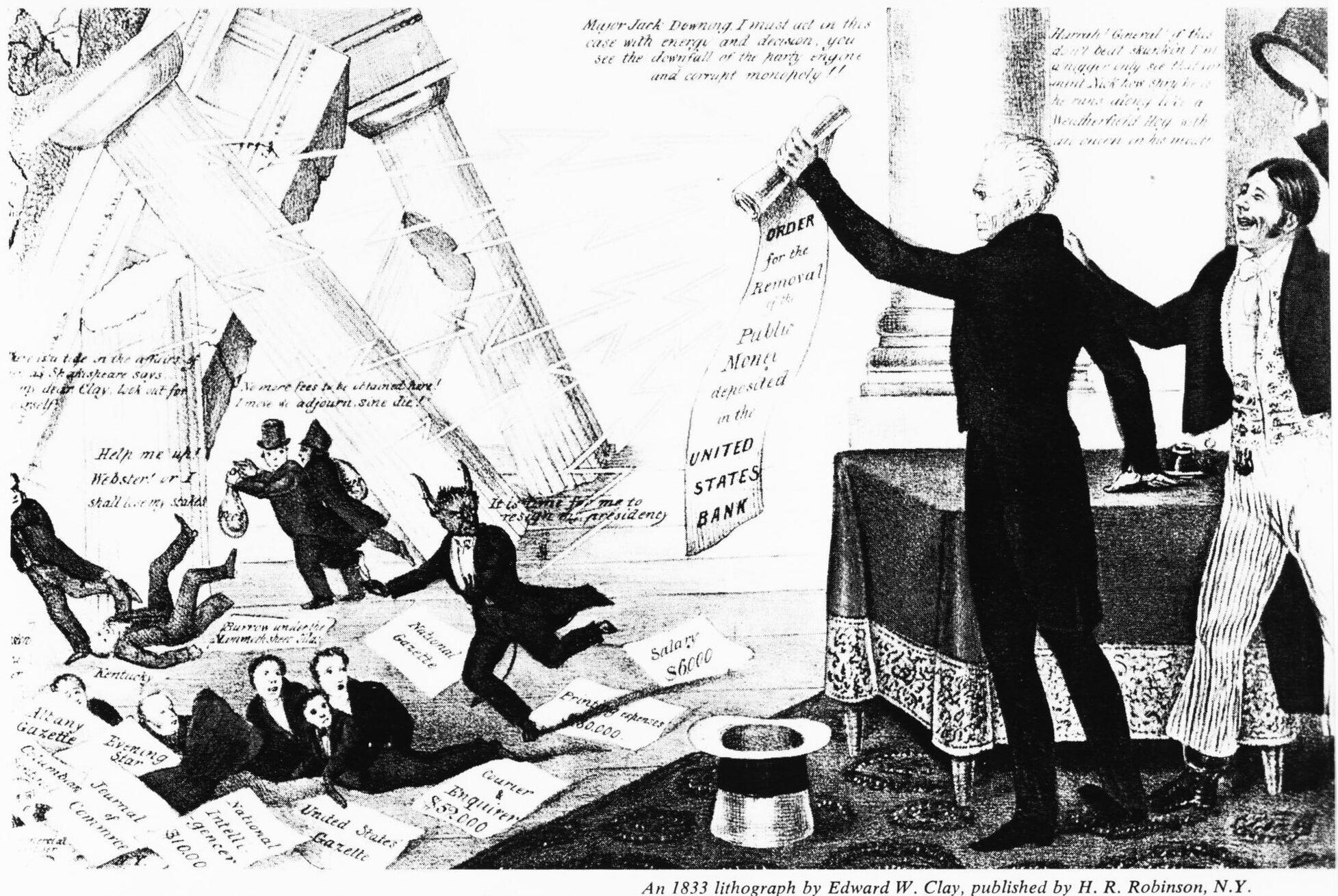

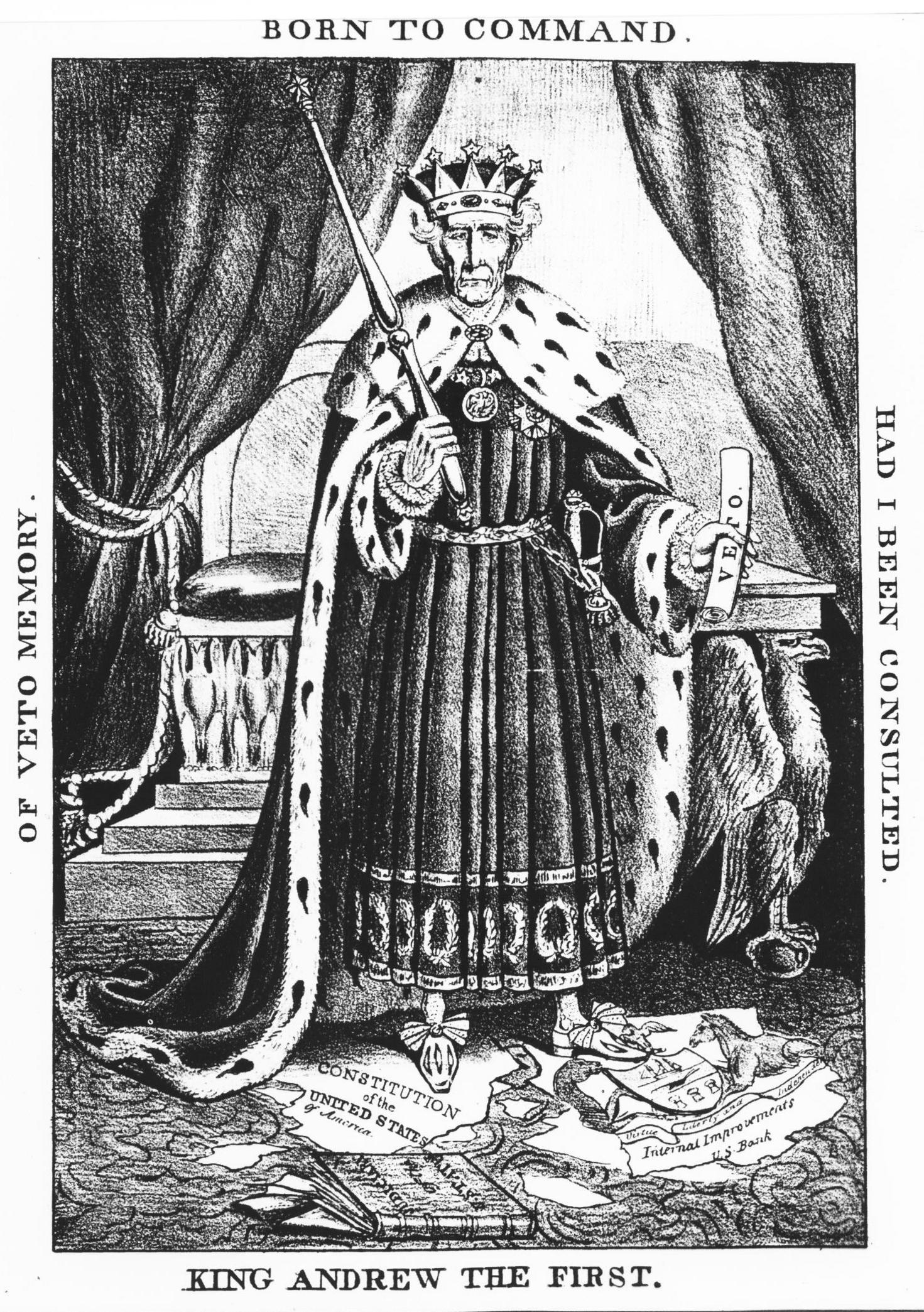

A previous discussion on the founding and dissolution of the First Bank of the United States (BUS) which existed from 1791 to 1811. After the First BUS recharter was defeated, the United States suffered defeat in the War of 1812, and suffered from a lack of fiscal order and an unregulated currency. As industrial and commercial interests expanded after the War of 1812, politicians advocated for the creation of a second Bank of the United States to promote the economy. After the war, there was sufficient support to overcome the opposition to the first BUS. Opponents of a second BUS had seen its charter as not only a threat to the Jeffersonian agrarianism and state sovereignty, but to slavery since, as John Taylor of South Carolina put it, "if Congress could incorporate a bank, it might emancipate a slave." The bank's constitutionality had been established in 1819 in McCulloch v. Maryland, a landmark decision in constitutional history, but many still felt the establishment of a bank by the Federal government was unconstitutional. The Bank of the United States would be a depository for collected taxes, make short-term loans to the government, and could serve as a holding site for incoming and outgoing money. The main goal of the bank would to promote commercial and private interests by making sound loans to the private sector. The second BUS charter was signed into law on April 10, 1816 by President Madison. The second BUS was modeled on the first with the government owning 20% of the $35 million in equity, divided into 350,000 shares of $100 each. The bank had 4000 investors of which 1000 were Europeans, though the bulk of the shares were owned by a few hundred wealthy Americans. The second BUS had 25 branch offices in addition to its main office in Philadelphia. After the BUS was established, southern and western branches issued credit to fund expansion. This led to a financial bubble that burst in the Panic of 1819 leading to sharp declines in property prices, much as happened in 2008 when the most recent bank-induced bubble led to a financial crash. The public was unhappy about the prolonged recession that resulted from the BUS-induced Panic of 1819. Nicholas Biddle took over the BUS in 1823, and switched to a sound money policy. At that point in time, state-chartered banks could issue their own currency, but when their currency was deposited at the BUS, the bank would demand gold or silver from the issuing bank, thus controlling and limiting the issuance of currency by state banks. Because the number of banks in the United States grew from 31 in 1801 to 788 in 1837, state-chartered banks began to oppose the BUS because it limited their ability to issue currency and make profits. Shares in the Second Bank of the United States were the most liquid and most secure of all shares listed on US exchanges. The bank paid steady dividends to its shareholders, increasing the dividend from $5 in 1819 to $7 by 1834. Since the US government succeeded in paying off all of its outstanding bonds by 1835, the stock of the Bank of the United States was not only the largest issue on the stock exchange, but it was also the safest since it was backed by the United States Government, or so it seemed. Andrew Jackson had received the largest number of votes, the largest number of electoral votes and carried the most states in 1824, but failed to gain a majority. The House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams as President instead. When Jackson was elected in 1828, he felt rancor toward his opponents for keeping him from being chosen President in 1824. Jackson was a populist, and even though the Bank was popular because the economy was growing as a result of its sound-money policies, Jackson opposed the BUS as unconstitutional, corrupt and a danger to American liberties. In Jackson's mind, the BUS was at the center of the class warfare of the 1830s which pitted "farmers, mechanics and laborers" against the "rich and powerful," in words that seem reminiscent of Occupy Wall Street's opposition to the 1%. Jackson's opposition to the BUS led to the "Bank War" between Jackson and Biddle over the rechartering of the Second BUS. The recharter of the Second BUS became the focal point of the 1832 election. Pro-bank forces tried to get a vote on the charter prior to the 1832 election to discourage a Presidential veto, but anti-bank forces delayed the vote until after the election when Jackson vetoed the recharter, and which Congress failed to override. One of Jackson's first actions after re-election was to remove all government deposits from the Bank of the United States and spread them out among state-chartered banks, crippling the second BUS. Biddle counterattacked by contracting bank credit, but this led to a financial downturn which only added to opposition against the BUS. Business leaders in American financial centers became convinced that Biddle’s war on Jackson was more destructive than Jackson’s war on the Bank. When the Second BUS's charter expired in 1836, the bank rechartered as a Pennsylvania private corporation. In 1839, the bank suspended payments, and it went into liquidation in 1841. As was true of the first BUS, the bank was born of politics and died of politics. Andrew Jackson won the bank war, and the BUS charter lapsed in 1836. At one point during the Bank War, Jackson had offered to charter a new bank if it were publically owned, and it did not compete with state-chartered banks by issuing commercial loans. Although Jackson's version of a Central Bank never came into existence, when the Federal Reserve was chartered in 1913, Jackson had his way at last because the Federal Reserve is 100% owned by the government, does not compete with commercial banks, and to avoid the political battles over rechartering, the charter for the Federal Reserve is perpetual. Today the battles are over who is appointed Federal Reserve chairperson, not over whether the Federal Reserve should be rechartered. The advocates of hard money and soft money continue to battle over interest rates, quantitative easing, the Federal deficit, funding the government and the other subjects related to the availability of credit. The Bank War was not just part of the 1832 Presidential election, but it is part of every election and almost every battle involving the economy today, and in the future. Source: |

| Invest As If The Sun Is Coming Up Tomorrow Posted: 13 Oct 2013 07:00 AM PDT I did a long interview with Forbes, we discuss some investing themes and ideas:

Its a long interview, and that’s just a flavor. You can see the whole thing here.

Source:

|

| Posted: 13 Oct 2013 04:30 AM PDT Good Sunday morning. Some reads to round out your weekend:

What are you having for brunch?

Shutdown Stirs Investor Anxiety |

| Posted: 13 Oct 2013 03:30 AM PDT |

| The Economics of Student Loan Borrowing and Repayment Posted: 13 Oct 2013 02:30 AM PDT |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment