The Big Picture |

- Forecasting Inflation? Target the Middle

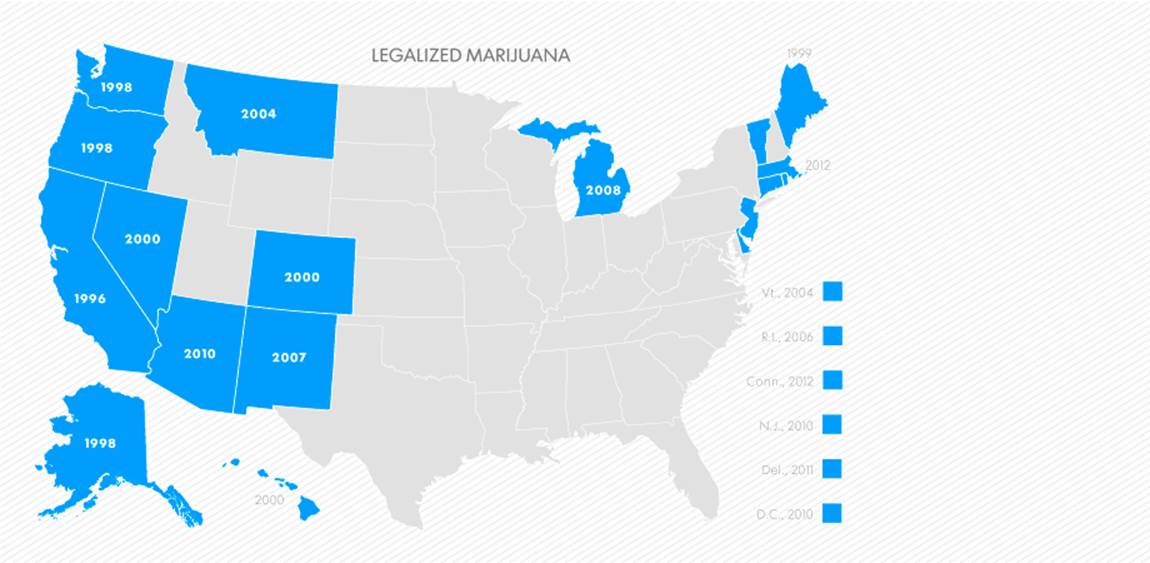

- Medicinal marijuana markets: Weed goes legit

- Iraq War Could Have Paid For 100% Renewable Power Grid

- TBP Redesign: Final Thoughts

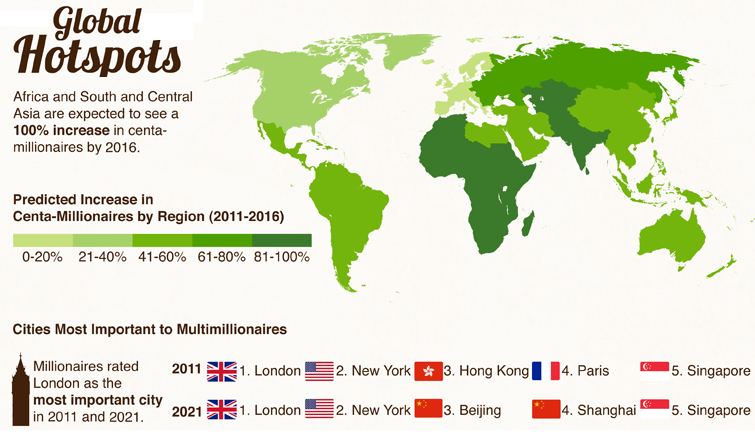

- Mega Millionaires: Property & Wealth

- 15,000 Point Round Trip

- 10 Weekend Reads

- Jeff Bezos Revealed

| Forecasting Inflation? Target the Middle Posted: 14 Apr 2013 02:00 AM PDT Forecasting Inflation? Target the Middle

The Median CPI is well-known as an accurate predictor of future inflation. But it's just one of many possible trimmed-mean inflation measures. Recent research compares these types of measures to see which tracks future inflation best. Not only does the Median CPI outperform other trims in predicting CPI inflation, it also does a better job of predicting PCE inflation, the FOMC's preferred measure, than the core PCE. At the end of 2012, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) adopted a new guideline for determining when it would consider raising interest rates. What is different about the guideline is that it gives specific thresholds for various economic indicators, which if reached, would signal a change in the Committee's interest-rate target. These thresholds were spelled out in the meeting statement: "…the Committee…currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6 1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored." While the unemployment-rate threshold is expressed in terms of current conditions, the inflation threshold is in terms of the outlook for inflation. By specifying the inflation threshold in terms of its forecasted values, the FOMC will still be able to "look through" transitory price changes, like they did, for example, when energy prices spiked in 2008. At that time, the year-over-year growth rate in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) jumped up above 5.0 percent but subsequently plummeted below zero a year later when the bottom fell out on energy prices. At the time, the Committee maintained the federal funds rate target at 2.0 percent, choosing not to react to the energy price spike. Under the explicit inflation threshold, the Committee will not lose its ability to remain forward looking, and will rely on forecasts of inflation. To help inform those inflation projections, Chairman Bernanke, in a recent press conference, stated that the Committee "will consider a variety of indicators, including measures such as median, trimmed mean, and core inflation; the views of outside forecasters; and the predictions of econometric and statistical models of inflation." In this Economic Commentary, we highlight the usefulness of trimmed-mean measures (chiefly, the median CPI) in gauging the underlying inflation trend and forecasting future inflation. Drilling Down to the "Core"Perhaps the most well-known underlying inflation measure is the "core" Consumer Price Index (CPI).1 This measure excludes the prices of food and energy items because those were the two most volatile categories when the core CPI was conceived. While energy remains the most volatile broad category, food prices have become much less volatile in recent years. Exclusionary measures have a couple of drawbacks. First, they always treat price changes in the categories they exclude as noise. This becomes a problem if there is information on inflationary pressures embedded in those excluded categories. More importantly, these measures always treat the price changes that they retain as an inflation signal. For example, if an excise-tax increase pushed up the retail price of tobacco, even though that has little to do with inflation, it would get included in the core CPI, hence overstating underlying inflation. Fortunately, there are alternatives to the core CPI. One is trimmed-mean inflation statistics. These measures separate the inflation signal from relative-price noise by ignoring the most volatile monthly price swings. Calculating a trimmed-mean measure is relatively simple. The monthly price changes in the consumer market basket are ordered from lowest to highest price change, and the tails of the distribution are dropped. For example, the symmetric 16 percent trimmed-mean CPI cuts 8 percent (by expenditure weight) off of the low end and 8 percent from the high end of the price-change distribution. Then a weighted average is taken of what's left over. And calculating the median CPI, which is just an extreme trimmed-mean measure, is even easier, in that it uses only the price change in the middle of the distribution. There are a myriad of possible trimmed-mean inflation measures to choose from. Some are symmetric, in that they trim an equal amount from each tail, and some are asymmetric, in that they trim more from one tail than the other. But which trimmed mean should we pay attention to? And how confident should we be that the "best-performing" trimmed-mean measure over the past will remain so in the future? Some recent work from the Cleveland Fed—Meyer and Venkatu (2012)—attempts to answer those questions by evaluating the full set of symmetric and asymmetric trims. They are chiefly interested to see if any particular trimmed-mean measure can track future inflation better than all the other trims. Meyer and Venkatu find that the most accurate trimmed-mean CPI appears to vary across different sample periods. Over some time horizons, the inflation signal is strong enough that a less aggressive trimmed mean is sufficient (such as a 10 or 16 percent trimmed mean). However, over other time periods, a much more aggressive trimmed mean (like the median CPI) is necessary to separate relative-price noise from inflation signal. This poses a potential problem, because in "real-time" we are never sure of how aggressive we need to be with the trimming procedure. One strategy to deal with this issue might be to always use the most aggressive trimmed mean—the median CPI. However, before we do that, we want to be sure that we're not throwing away information that could be potentially useful in tracking underlying inflation. What we really care about is whether a particular trimmed mean is giving us a meaningful difference in forecasting power. Even though the "optimal" trimmed-mean measure changes over time, if its performance is not materially different from, say the median CPI, we can be confident in the inflation signal that is coming from the median CPI. This difference in forecasting power can be discerned using a simple statistical test. Testing the statistical significance of the most accurate trimmed-mean measure versus all others gives us an idea of how unique that performance is, in the sense that we will be able to visualize whether there is a tight grouping of equally performing trimmed means around the "best" trim, or whether there is a wide swath of trimmed-mean measures that have statistically similar forecasting performance. The results of this test are plotted in figure 1.

Figure 1 plots all the different possible trimming combinations, with the percent trimmed from the lower tail of the price-change distribution on the horizontal axis, and the percent trimmed from the upper tail on the vertical axis. The red line traces out the symmetric trimming points, from the zero-trim (headline) CPI in the lower left, to the median CPI in the upper right. The large swath in blue contains all the trims with the lowest forecast error and statistically similar forecasting accuracy.2 The huge swath of blue in figure 1 tells us, with 90 percent confidence, all the trimmed-mean measures contained within carry about the same forecasting accuracy as the most accurate trimmed-mean over that sample period. In other words, a 30 percent trimmed mean (one that cuts off 15 percent from each tail of the price-change distribution) carries about the same forecasting accuracy as the median CPI since 1983. Interestingly, figure 1 also suggests that there is a penalty to asymmetrically trimming, as moving the trimming points too far toward the upper left-hand or lower right-hand corners results in a significant reduction in forecast accuracy. For example, trimming 40 percent off the lower tail of the price-change distribution and only 25 percent off the upper tail would result in a meaningful deterioration in performance. So, which trimmed-mean measure should garner our attention? The recent study from the Cleveland Fed runs the test shown in figure 1 over multiple time periods. While the large swath of equally performing trimmed-means changes slightly between periods, the median CPI is always in that robust forecasting set. A Simple ForecastAny useful measure of underlying inflation should be able to quickly distinguish inflation signal from relative-price noise. Given this high signal-to-noise ratio, its near-term trend should be able to predict future inflation. Table 1 compares the forecasting accuracy, as measured in terms of root-mean-squared error (RMSE), of the near-to-longer term growth rates in the headline CPI, core CPI, and median CPI. A lower RMSE means a more accurate forecast, with a value of zero indicating perfect foresight. For example, taking the one-month annualized growth rate in the median CPI to forecast inflation over the next year yields a RMSE of 1.22, which is roughly 16 percent more accurate than the one-month percent change in the core CPI. Table 1. Forecasting Accuracy For CPI Inflation over the Next One to Two Years

As is evident in the figure, the median CPI has a lower forecasting error than the core CPI, and both are much more accurate than the headline CPI. Also, it appears that the median CPI more quickly sheds relative-price noise, as the greatest difference between it and the core CPI is over the very near term (one- through three-month annualized growth rates). In this sense, the median is more likely to act as an early warning system in the event that inflation starts to pick up. Forecasting PCE inflationSo far we've focused primarily on the CPI-based inflation measures, but the FOMC's explicit inflation objective is expressed in terms of the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index. There are significant differences between it and the CPI.3 However, inflation is a monetary impulse that affects prices in general, and over time, the inflation trend measured by the CPI and the PCE should be broadly similar. More importantly, any appropriate underlying inflation measure ought to be able to tease out that inflationary impulse regardless of which measure of retail prices it is based on. In the forecasting exercise below, we show that the median CPI is, by that definition, an appropriate underlying inflation measure, as it is useful in forecasting headline PCE inflation. In fact, it can even be helpful in forecasting core PCE inflation. Recent work by Meyer and Zaman (2013) evaluates the use of the median CPI in a class of statistical models known as Bayesian Vector Autoregressions (BVARs), which are often used for macroeconomic-policy forecasting. These statistical models efficiently estimate historical relationships between variables and use those correlations to forecast. Table 2 illustrates the usefulness of the median CPI in forecasting PCE-based inflation. We highlight these gains in forecast accuracy in two different exercises using a medium-scale (18-variable) monthly BVAR model. First, we add the median CPI alongside the core PCE in the model and compare forecasts of core and headline PCE inflation from one-month to 24-months ahead. Then we run a similar exercise where we replace the core PCE with the median CPI as the underlying inflation measure in the model and forecast headline PCE inflation. The values shown in the table are the forecast errors of the model that makes use of the median CPI relative to the one without. A value below 1.0 indicates that the forecasting model that uses the median CPI is more accurate. Table 2. Forecasting Accuracy in a More Complex Statistical Model

Notes: A value below 1.0 means the model with the median CPI is more accurate. Forecasting results from the Carriero, Clark, and Marcellino (2011) benchmark BVAR estimated recursively with an initial estimation period of January 1967 to December 1986. The forecast evaluation period begins in January 1987 and runs through 2011. As both exercises indicate, making use of the median CPI (either alongside or in place of the core PCE) aids in forecasting inflation. In general these gains are modest, roughly 5 percent, on average. However, for core PCE, the improvement in forecasting accuracy hits about 10 percent at horizons of 18 months and beyond. This suggests that the median CPI is an appropriate measure of underlying inflation—one that can overcome the idiosyncrasies of the price index it's based on and more completely uncover the inflationary impulse. ConclusionOur tests suggest the median CPI is useful tool for forecasting inflation. As such, it should prove useful in helping to gauge room between the near-term trend and the new inflation threshold. The use of the median CPI also has other benefits. First, it's the easiest trimmed mean to conceptualize, as it's simply the price change in the middle of the distribution. But it also holds an important communications advantage over the oft-used core CPI. In times when the relative prices of energy and food items are rising rapidly, use of the exclusionary core CPI makes the FOMC appear to be disconnected or insensitive, as it disregards subsistence items that consumers purchase much more frequently than, say, cars or new televisions. In communicating the stance of underlying inflation, hitting the one in the middle is far superior to excluding consumer necessities like food and energy. Footnotes

Recommended Reading"Trimmed-Mean Inflation Statistics: Just Hit the One in the Middle," Brent Meyer and Guhan Venkatu, 2012. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, working paper no. 12-17. "Bayesian VARs: Specification Choices and Forecast Accuracy," Andrea Carriero, Todd Clark, and Massimiliano Marcellino, 2011. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, working paper no. 11-12. "It's Not Just for Inflation: The Usefulness of the Median CPI in BVAR Forecasting," Brent Meyer and Saeed Zaman, 2013. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, working paper no. 13-03. "The Usefulness of Core PCE Inflation Measures," Alan K. Detmeister, 2011. Federal Reserve Board, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2011-56. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medicinal marijuana markets: Weed goes legit Posted: 14 Apr 2013 01:00 AM PDT Medicinal marijuana markets: Weed goes legit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iraq War Could Have Paid For 100% Renewable Power Grid Posted: 14 Apr 2013 12:30 AM PDT For the Price of the Iraq War, The U.S. Could Have a 100% Renewable Power SystemPosted on April 11, 2013 by WashingtonsBlog What Are We Choosing for Our Future?Wind energy expert Paul Gipe reported this week that – for the amount spent on the Iraq war – the U.S. could be generating 40%-60% of its electricity with renewable energy:

But Nobel prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz estimated in 2008 that the Iraq war could cost America up to $5 trillion dollars. And the Brown University study actually concluded that the Iraq war could end up costing $6 trillion dollars over the next 40 years. Since $6 trillion is one and a half times as much as the $3.9 trillion estimate used by Gipe and Freehling, that means that the Iraq war money could essentially convert 100% of U.S. power to renewable energy. True, comparing future interest payments to present renewable energy costs may be comparing apples and oranges. But given that the nation's top energy experts point out stunning breakthroughs in energy production, distribution, storage and conservation will drastically lower the costs of alternative energy, that $5-6 trillion could perhaps fund 100% renewable energy production: ~~~ ~~~ Moreover, given that war is very harmful for the economy, the costs of the Iraq war including the drag on the economy raises the price tag well above $6 trillion. So 100% of renewable energy funding may be realistic. It is ironic, indeed, that the Iraq war was largely about oil. When we choose subsidies for conventional energy sources – war or otherwise – we sell our future down the river. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Posted: 13 Apr 2013 03:00 PM PDT The blog redesign is now just about finished. There are still a handful of tweaks left, but I am 90% of the way there. The feedback from readers — see this and this — was very helpful. I have seen immediate improvement in the site: The main page loads 4X faster; it now generates much more detailed page analytics (what people are and are not clicking on/reading); the page views/visitor have increased. The average length of time per post has also increased. Based on your comments and emails, here are the changes I implemented:

Since the last few iterations, the site is light and fast and pleasing to the eye. I still think the navigation links up top are too big and spread out – since the way I run my business is strictly word of mouth and referral, I prefer these to be smaller and less in your face. Also, I think I can get rid of “Home” and just go with: Asset Management/Speaking/Book /Contact. I still have a few other things left to tweak:

The 5 little icons correlate to the tabs in the old design. According to Google Analytics, those old icons were hardly clicked. The reason, I assume, is as soon as you scrolled an inch or two, they were off your screen. Your most emailed questions and their answers are after the jump . . .

Q: I don’t like clicking to open each new post. A:When we had all 10 posts open, it loaded very slowly. The new version does not have to load 10 posts of graphics, charts, videos, etc. And, I now get analytics as to what specific posts you folks actually are reading. Its a huge improvement Q: I am reluctant to click on something that I may not like. A: You have to have a wee bit of faith in me that I ain’t publish crap — I would hope that after 11 years, 25,000 posts and a 137 million page views, I have earned at least a teeny bit of trust. Besides, its a click — what’s that cost you? Q: I might be interested in posts if you gave me more info — a teaser paragraph A: That’s a really good idea. Currently, the teaser intro is automated (the first XX words), but I can use a specific excerpt as a teaser (I just have to remember to cut & paste it each post). Q: Sometimes the home page loads slowly. A: Its likely the adverts. When we see an add slowing the site down it gets tossed. (Please email me if an ad is problematic) Q: Could you set it up so that the post expands within the open page like Andrew Sullivan or FT Alphaville does? A: I am looking into that; but note that Sullivan is now a subscription site. He bills his readers for the extra bandwidth programming costs ! -Barry | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mega Millionaires: Property & Wealth Posted: 13 Apr 2013 12:30 PM PDT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Posted: 13 Apr 2013 06:30 AM PDT As stocks mark new all-time highs, many investors are left behind

Imagine this: The Dow Jones industrial average travels 15,000 points, and you have nothing to show for it. Same for the S&P 500-stock index, a full 1,800 points, and the net gains are zero, nada, zilch.How did this happen? If you employ a buy-and-hold strategy, the round trip in the equity markets is simple math. Dow 14,000 down to 6,500 and back again equals about 15,000 points. Any stocks bought in late 2007 are just now, after six long and tumultuous years, returning to break even, even as stocks mark new all-time highs. What does this mean for investors? Let's look at alternative investing approaches, including what you could do to avoid this. A few strategies you can easily deploy will make the next round trip — and, yes, there will be one — much more profitable. First, a few words about new all-time highs. Ned Davis Research did a study (brought to my attention by Mark Hulbert) that looked at what happened when the S&P 500 made a new market high after a bear market. Since the 1950s, there were 13 such instances. The mean bull market "continued for another 644 days — nearly two years — and, in the process, gained an additional 40.3 percent." The median case was less impressive — the bull ran for one more year and gained more than 18 percent. The weakest example was 2007, with the inflection point coming less than six months later and under 3 percent higher following new highs. Why is this noteworthy? Mostly because so many investors have fought this rally the entire way up. I suspect the recency effect is to blame — the residual psychological trauma caused by the 2008-09 crash is still so fresh in people's minds that they have become fearful of risk. Aversion to losses has investors so focused on avoiding any drawdown that they end up missing what turns out to be the best rally in a generation. New highs raise the fear of yet another market top. This is an emotional reaction. Rather than give in to your ancient lizard brain, let's put that big ole underutilized neocortex to work. To do that, we have to consider a few standard market metrics and see whether they tell us anything. Valuation: Markets today are not cheap or expensive. Despite doubling since the market lows, the S&P 500 trades at 15.4 times earnings. The average for all bull markets since 1962, according to Bloomberg, is just under 20 times earnings. From a valuation perspective, markets are not unreasonably priced. Market internals: Healthy markets can be described as having a strong trend, good leadership and, especially, good breadth. What that last term means is that many stocks are participating in the overall market trend. We track this through the advance-decline (A/D) line, a measure of how many stocks are rising versus falling. During market tops, we tend to see new highs made even as the A/D line diverges. This happens because major market tops are usually preceded by signs of increasingly selective buying. Think of the Nifty Fifty in the 1970s or the four horsemen of the Internet in the late 1990s. I also watch how many new 52-week highs are being made versus new lows. When this diverges from prices, it can be a warning sign. Global markets: The internals in the United States remain fairly robust. And in Britain, markets have been reasonably strong. We also have seen a big rally in Japan. The same is not true for the rest of the world. The Shanghai index has had troubles for two years. India, Hong Kong and Australia also have seen a rough patch. South Korea and Taiwan have been deteriorating. And while everyone knows that Spain and Italy have been a mess, we are starting to see signs of weakness in the market conditions in France and Germany. Overbought markets: A gain of 10 percent usually makes for a decent year — and the United States achieved that in three months. Markets may have gone too far too fast, becoming what traders like to call "overbought." The way overbought markets work off these excesses is through consolidation. It may take a few weeks or even months for the market to digest these gains and for earnings to catch up to prices. These factors suggest that the bull market is not yet over, but we could start to see some choppy waters. Eventually, this bull market will come to its natural end, as every one does. Instead of just buying and holding, there are a few strategies to take advantage of any market volatility: ●Dollar cost averaging: The simplest and, for many people, the best option. Each month, you contribute a fixed dollar amount to a handful of broad indices via ETFs. When stocks are cheap, you are buying more shares of them. When things get expensive, you are buying less. Think about what this would have looked like over the course of a round-trip cycle like 2007-13. As markets fell, you kept making equity purchases. As they bottomed, you bought more shares; as market rallied to new highs, you bought increasingly fewer shares. This makes your weighted average purchase price closer to the lows than the highs. Had you been doing this last cycle, you would be very happy today. Note: This works best when you can set it on autopilot. Online brokers can help you automate this process. ●Portfolio rebalancing: This two-step process is a little more complex and involves more planning. The first step is to set up an asset-allocation model, which is not nearly as complicated as it sounds. Decide on a portfolio of various asset classes, including stocks, bonds, real estate and commodities. Let's make your hypothetical allocation 60 percent equities, 30 percent bonds, 6 percent real estate and 4 percent commodities (60/30/6/4). Depending upon what markets do, different parts of your portfolio will eventually move away from your original percentage allocations. Over time, your allocation has morphed into 62/28/7/3. On a regular basis, you sell a little of what has become overweighted and buy a little of what is underweighted to restore your portfolio to its original allocation. To keep costs down, do this less frequently for smaller portfolios (annually) and more frequently for larger portfolios (quarterly). You can break down asset classes further: equities into classes such as domestic, international, dividend, growth, small cap, etc.; bonds into Treasurys, corporates, munis, TIPs. Rebalancing works thanks to mean reversion. Asset classes that get ahead of themselves tend to revert back to more typical valuations eventually. Rebalancing means you are selling a little of what is pricey and buying a little of what is cheap. Reams of academic research shows that rebalancing creates risk-free gains over longer periods. It is one of the few free lunches on Wall Street. Like dollar cost averaging, this strategy works only if you have the discipline to follow it. (Rebalancing as equities crash is more difficult than it sounds). To overcome the emotional elements, work with an online broker who can help you automate the process. ●Asset allocation tilt: "Tilting," which is more complex than simple rebalancing, means shifting your allocation in more defensive or aggressive directions based on very specific predefined factors. These could be economic, valuation or even market-based. For example, you could tilt your portfolio into a greater equity exposure after a market falls a specific amount. A 60/40 portfolio might become 65/35 after equity markets fall 30 percent. An aggressive allocator would add 5 percent at levels of 40 percent and 50 percent off of highs. (Easier said than done, I know). One could tilt a portfolio more defensively as valuation levels rise above specific levels, i.e., 22 P/E for the S&P 500. ●Market timing: The granddaddy of the big cycle, the holy grail for traders. Market timers face two challenges: They have to identify when markets are topping and have the emotional fortitude to leave the party just as it really is getting going. Selling when things are doing well is much harder than it looks. Then they have to do the same thing at the other end: They have to identify when markets are bottoming. This typically occurs when it looks as if the world is going to hell. Despite every instinct in their bodies, timers then must be able to jump back in. Market tops are long-drawn-out processes; bottoms are emotional, panic-filled events. Very, very few people can call either on a timely basis. You are not one of those people. ~~~ You have alternatives to simply throwing money at your portfolio and hoping for the best. Dollar cost averaging and portfolio rebalancing are strategies that will improve your returns — assuming you have the discipline to stay with them. ~~~ Ritholtz is chief executive of FusionIQ, a quantitative research firm. He is the author of "Bailout Nation" and runs a finance blog, the Big Picture. On Twitter: @Ritholtz. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Posted: 13 Apr 2013 03:30 AM PDT Some longer form reading for your weekend enjoyment:

Whats up for the weekend?

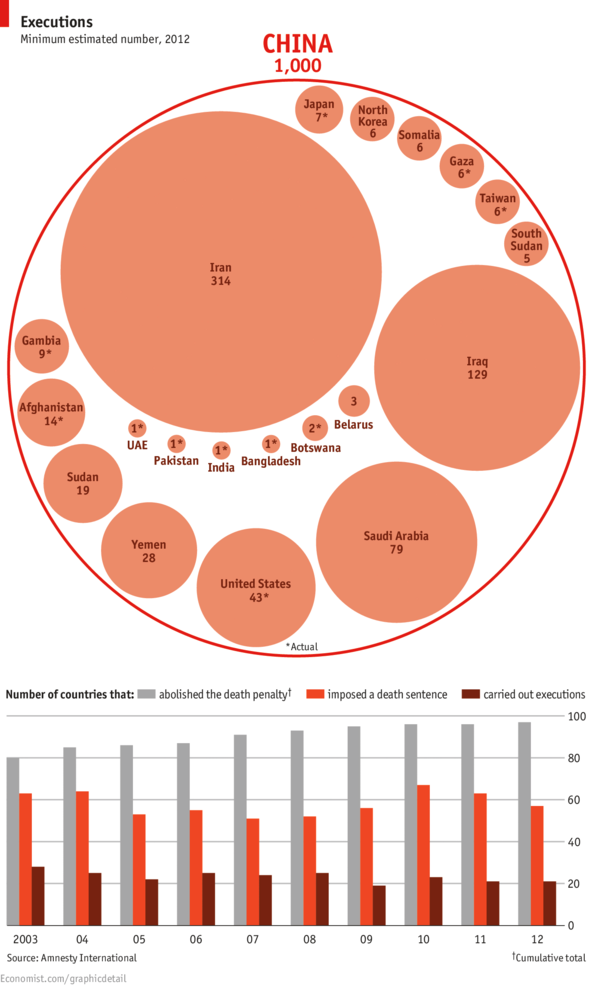

Death penalty Worldwide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Posted: 13 Apr 2013 03:00 AM PDT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Big Picture To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment